Apple’s iOS App Store changed the way we think about software

Ten years ago, finding good software was a headache.

Ten years ago today, Apple officially launched the iOS App Store and -- for better or worse -- it helped rewrite the rules of society. The iPhone, which debuted about a year prior, came with just north of 12 built-in apps to start. But with the coming of iOS 2.0 and the App Store, the sort of functionality you could squeeze out of Apple's smartphone was only constrained by a developer's imagination ... and how much storage you had left.

Ironically, Steve Jobs was firmly against the idea of iPhones running third-party software -- as Walter Isaacson wrote in his acclaimed Jobs biography, the Apple co-founder "didn't want outsiders to create applications for the iPhone that could mess it up, infect it with viruses or pollute its integrity," preferring that developers instead build robust web apps for mobile devices. Jobs eventually changed his mind, and in doing so, helped bring to life a new mobile-first industry. Now we navigate, read, call cars, pay bills, find jobs, waste time, get high and search for love with help from the apps we carry with us every day, and at this point that seems unlikely to ever change.

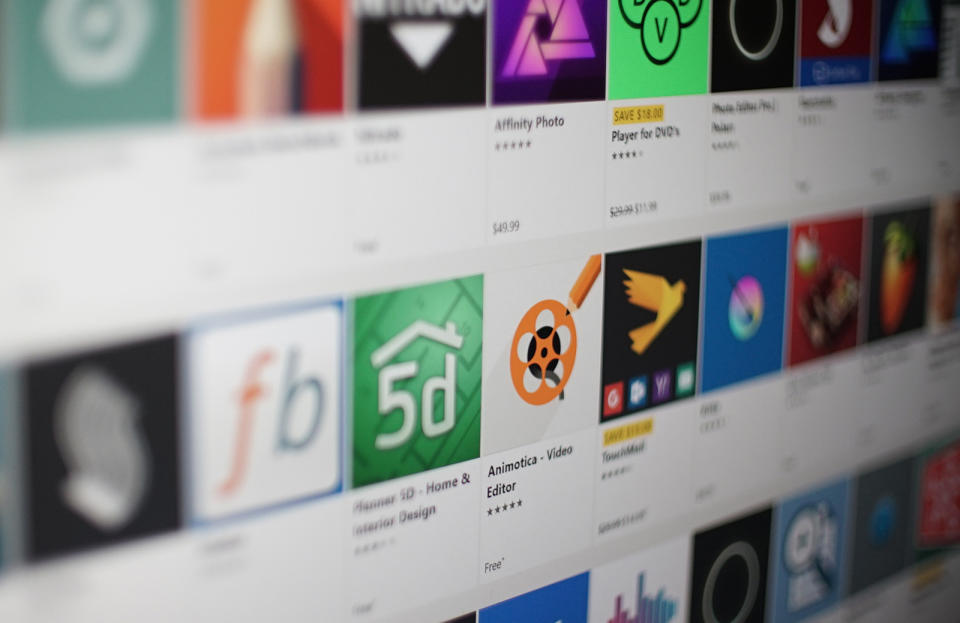

You don't need us to tell you that the intervening years have seen the number of apps available explode, or that they're they are more sophisticated than ever. (The number of fart apps available for download now is, thankfully, a far cry from what it used to be.) And Apple is always keen to talk about the App Store's financial impact: Developers have collectively made more than $100 billion since launch. After 10 years, though, it's important to keep in mind how Apple's App Store changed the way average people thought about software. It wasn't just something for computer aficionados to obsess over -- downloading apps without a second thought became part of the fabric of everyday life. The era of using your smartphone for everything started in earnest 10 years ago today, and I'd argue it's because of one thing: accessibility.

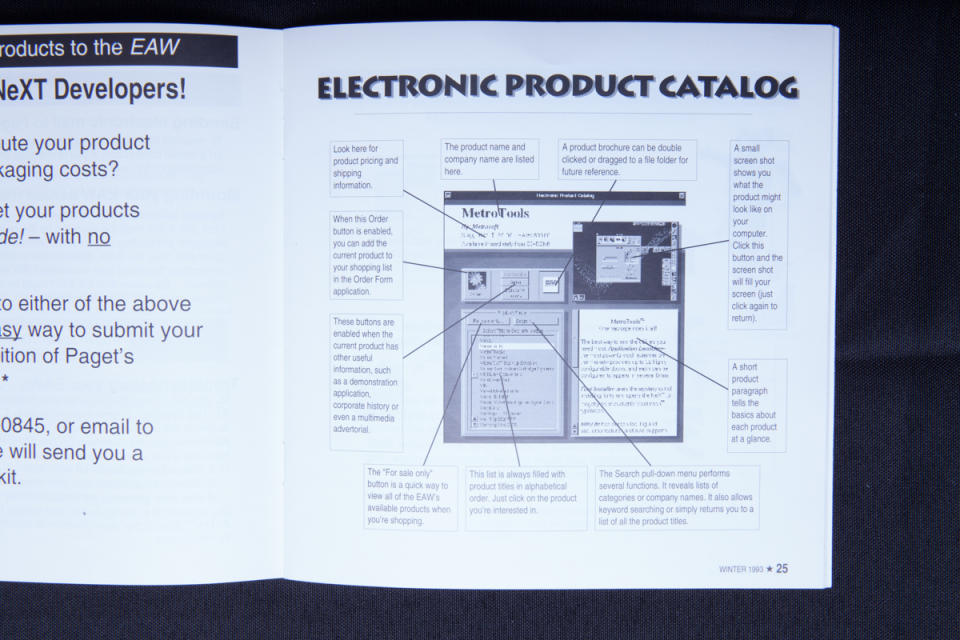

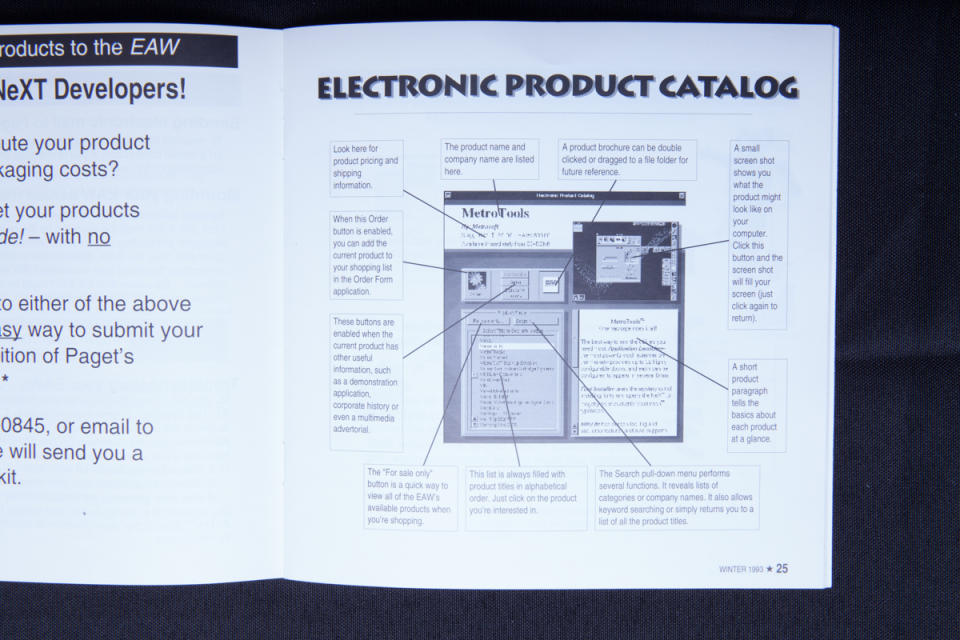

At the risk of sounding obvious, Apple didn't pioneer the idea of a centralized place to download software tailor-made for your machine. One of the first commercial examples appeared in 1991 as a way to distribute and manage the rights for Steve Jobs's NeXT computers -- a niche market if there ever was one. For much of the '90s and early '00s, though, traditional PC users had to dig up new software the hard way.

Consider Windows. Finding handy new software meant lots of trawling the web, reading forums and blindly installing .exes. Portals like Download.com and Softpedia certainly helped, but finding that one crucial bit of software to solve a problem very frequently felt like picking a needle out of a haystack. For a long time, Linux users arguably had an easier time of things since they could easily access software repositories to install not just complete software packages but system tweaks and drivers with a little command line magic. These repositories were helpful, sure, but could be tricky for novices to navigate and didn't help the majority of people using more widely used operating systems.

Things weren't much better for the basic cellphones and early smartphones of the day. The kind of software available for the former generally wasn't much to write home about -- games were pretty basic and the limited horsepower available meant you were often hard-pressed to find valuable third-party utilities. Carriers were the big players in software distribution -- they got in on the action by building out digital stores like Verizon's Get It Now (2002) and AT&T's MEdia Mall (2004), with the added benefit of being able to stick application charges right onto your monthly bill.

If you were using, say, a Windows Mobile device, there was plenty of free and paid software out there -- you just needed to know where to look. Meanwhile, finding boxed software for Palm's Treo in a store was fairly common, but you could also purchase applications straight from Palm and either sideload from a PC or initiate an install right from the phone's web browser. The results were usually worth the effort, but the process was typically less than elegant.

And then came the iPhone and its App Store. Compared to the thousands of apps already available for Treos and Windows Mobile devices, the 500 apps in the App Store at launch seemed paltry at best. Because developers couldn't officially publish software for the iPhone outside of the App Store, working inside Apple's walled garden was the only way most people could add new features to their iPhone. (While it's far less popular than it used to be, let's not forget jailbreaking was a viable alternative for a long time.)

The process of finding and installing apps on early smartphones was awfully similar to how things worked on traditional PCs -- you'd sometimes find lots of software in one place, but otherwise, you had to spend time searching elsewhere for the right tool. Apple's insistence on keeping software strictly within the App Store's walls might have pissed off early power users, but it ensured that the ability to flesh out its devices with new functionality would only ever take a few taps on a screen.

For a public that was growing hungry for novel ways to use their iPhones, and for the developers that profited from that hunger, that simplicity was crucial. Everything you needed was in one place. And it didn't matter that your iPhone was just like every other one out there; your choice of apps made it uniquely yours. That dead-simple accessibility, combined with the iPhone's built-in popularity, helped build a kind of frenzy around mobile software that desktop applications had never come close to matching.

In time, it became clear that the ease of downloading apps had on some level changed the way the general public thought about mobile software as a whole. By removing the barriers required to install something, Apple fueled a sort of unending appetite for the new, little thrills apps could provide. Who among us hasn't downloaded a few new titles from the App Store just to see if they were any good? And if they weren't, who hasn't deleted those apps and moved onto the next one in search of a new photo filter, a new fleeting dopamine hit?

If you had trouble finding an app that did exactly what you needed, no problem -- just delete it and try again. App discovery can be a big problem for developers trying to stand out among countless competitors and for users searching for the good stuff. That said, the stakes of an app install are so low and the potential value so high, we collectively embraced this new mode of consumption. In a recent quarterly earnings call, Apple confirmed that its install base had swelled to 1.3 billion devices -- that is, there are 1.3 billion bits of Apple hardware, be they phones, tablets, computers and set-top boxes, in use out there; iOS devices obviously make up a considerable chunk of that total number. That's a pretty big number, but it pales in comparison to the number of apps downloaded since the App Store's launch: more than 180 billion.

The bite-size pricing model developers only helped. Top-tier software and games on traditional desktop PCs usually required nontrivial sums of money to change hands. Apps might not have provided the same level of functionality or the same flawless graphics as desktop software, but they were cheap, accessible, and — ultimately — inescapable.

Apple isn't single-handedly responsible for this software revolution, but it got the ball rolling. After people's response to the original iPhone, Google made sure that Android had an app store of its own -- the original Android Market -- when it debuted on the T-Mobile G1 in October 2008. BlackBerry, which then still produced its own hardware, launched its own App World in April 2009. Microsoft built an app marketplace for its aging Windows Mobile OS in 2009 (when it was already too late) and put together a successor store when the sleeker, more capable Windows Phone 7 launched the following year.

None of this is to suggest that these companies wouldn't have built app stores anyway, but they helped reinforce a new of way thinking about software that Apple helped unleash. The App Store helped transform software from something to be researched and agonized over into something to be consumed casually and effortlessly on a massive scale. Trite as it may sound now, the company's one-time marketing mantra holds true even across platforms: if there's something you want to do on your phone, there's an app for that. And another. And another, and another, ad infinitum.