Study maps where golden eagles are safe from wind turbines

Researchers have completed a novel study that may help the wind farm industry avoid protected golden eagle habitats. Wind turbine blades reportedly kill up to 300,000 birds per year in US, which is admittedly a small percentage compared to those killed by your cat. Still, the golden eagle is particularly susceptible, considering that around 100 individuals were killed last year by a single wind farm in Altamont, California -- and there are only 500 breeding pairs in the state. The new study posits a simple idea: Why not plot both golden eagle habitats and the areas with the best wind farm potential, and make sure the areas don't intersect?

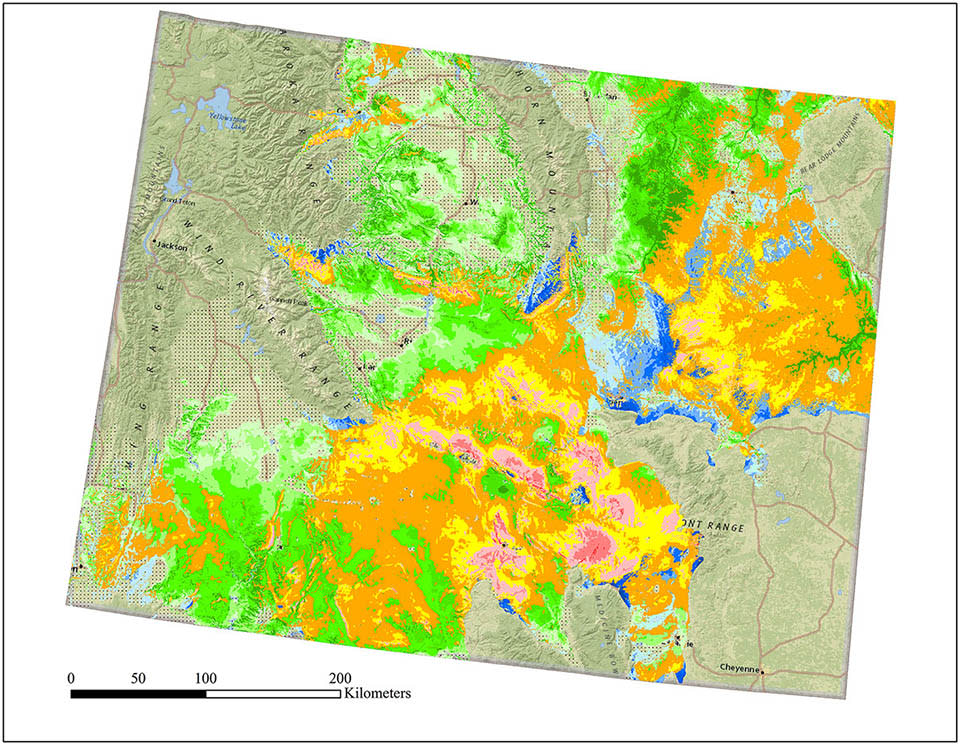

University of Waterloo and Colorado State U researchers gathered nesting data from various regions in Wyoming, which has second highest golden eagle population in the US. They also plotted regions with the highest wind-development potential in the state, which is America's fifth largest producer of wind power. The result is a study that shows the best regions for both turbines and established golden eagle nests (below, with the ideal areas in blue). The authors note that no existing wind farms are located in the green regions most preferred by the birds. However, there are many turbines located in the orange areas that have less-than-ideal winds but plenty of eagles.

Though golden eagles aren't the only birds threatened by wind farms, the study's authors hope that the well-known species will grab the public's imagination and spur cooperation between land-management agencies and industry. More concretely, the maps also provide wind farm developers with information that can help them avoid the eagles' habitats. "Our work shows that it's possible to guide development of sustainable energy projects, while having the least impact on wildlife populations," said Waterloo professor Brad Fedy.

[Lede image credit: Shutterstock / cristovao]