Making sense of the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica nightmare

The firm harvested data from 50 million Facebook profiles, but now what?

Over the weekend, a series of bombshell reports from The New York Times, The Observer and The Guardian told the story of Cambridge Analytica (CA) and how it harvested information from 50 million US Facebook profiles -- mostly without consent. The reports were (and remain) chilling.

The idea of a data science company no one has ever heard of attempting to poke around in a country's collective psyche sounds like a plot out of Black Mirror, and yet here we are. More troubling is the idea that the sort of mass-scale psych profiling Cambridge Analytica allegedly carried out was done with a political endgame in mind. The jury is still out on whether its work with data ultimately swayed the result of the 2016 election -- CEO Alexander Nix denies using this kind of data-driven "psychographic" profiling for Donald Trump's presidential campaign -- but by now it's clear that Nix isn't overly concerned with ethics. Let's take a closer look at what you need to know about Cambridge Analytica and the firestorm it ignited.

What is Cambridge Analytica?

Cambridge Analytica is a political data analytics firm and a subsidiary of a larger behavioral research firm called Strategic Communication Laboratories (SCL). SCL's stated mission seems at once both dry and ominous: it aims to "create behavior change through research, data, analytics, and strategy for both domestic and international government clients." CA's goal of effecting behavioral change doesn't stray too far from its parent company's mission, but the firm was created (with help from billionaire right-wing financier Robert Mercer) in 2013 to bring a specific kind of expertise to bear on the American electoral process.

By mashing up different kinds of personal data scraped from the internet, Cambridge Analytica sought to build "psychographic" profiles assigned to people who could later be pursued with specifically targeted ads and content. The firm made headlines in earlier election cycles because of ties to Senator Ted Cruz's presidential bid. But in 2016, Jared Kushner tapped it to take over data operations for the Trump campaign. Later, reports from The Guardian's Carole Cadwalladr indicated that Cambridge Analytica had done work to identify voters in the UK that could be persuaded to back the Brexit movement.

In other words, it's a lot more than your typical data science company. CA whistleblower Christopher Wylie was pointed in his assessment of the firm in an interview with The Guardian: "It's incorrect to call Cambridge Analytica a purely sort of data science company or an algorithm company -- it is a full-service propaganda machine."

How did Cambridge Analytica get 50 million people's data?

With a little outside help. To understand the story, we need to rewind to 2014 when Aleksandr Kogan -- a psychology researcher at Cambridge University -- created a Facebook app called "thisisyourdigitallife" with a personality test that spit out some kind of personal prediction at the end. To build credibility, the app was originally labeled a "research app used by psychologists," but that was only part of the truth -- as it turned out, Cambridge Analytica covered more than $800,000 of Kogan's app development costs. (Kogan also got to keep a copy of the resulting data for his trouble.) Some US Facebook users took the personality test as a result of ads on services like Amazon's Mechanical Turk and were paid for their efforts, but it's unclear how many chose to take the test on their own.

All told, some 270,000 US users took the test, but CA obviously walked away with data on many more people than that. That's thanks to a very specific Facebook peculiarity.

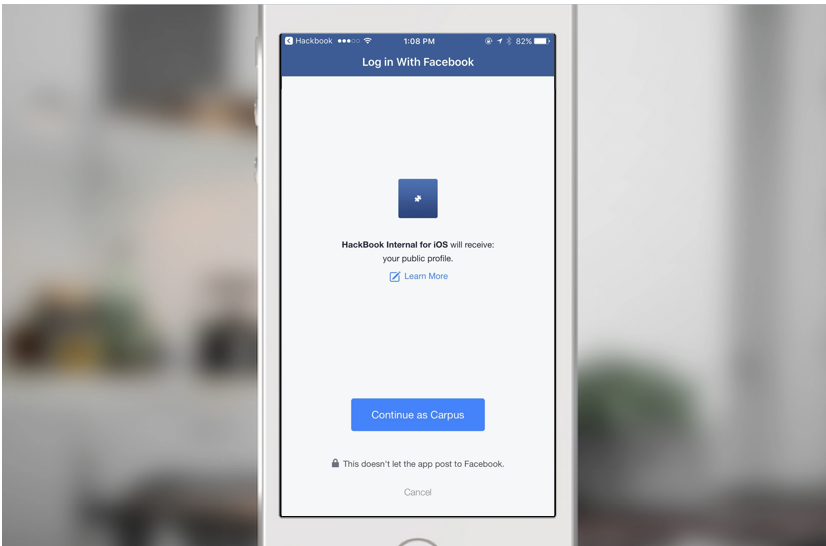

If you have a Facebook account, you've almost certainly used Facebook Login before -- it lets you create an account with a third-party app or service (or log into an existing account) with your Facebook credentials. It's incredibly convenient, but by using Facebook Login, you're tacitly giving developers of Facebook apps access to certain kinds of information about yourself -- email address and public profile data, for instance, are available to developers by default.

In 2014, however, using Facebook Login didn't just mean you were offering up your own data -- some data about the people in your social network was up for grabs too. (Facebook later deprecated the API that let this happen because, well, it's just creepy.) Those thousands of people who logged in to Kogan's app and took the test might have gotten the personality predictions they were looking for, but they paid for them with information about their friends and loved ones. Whether those results were ultimately valuable is another story. Kogan himself later said in an email to Cambridge coworkers (recently obtained by CNN) that he had provided "predicted personality scores" of 30 million American users to CA's parent company, but the results were "6 times more likely to get all 5 of a person's personality traits wrong as it was to get them all correct."

Was this really a data breach?

For better or worse, no. Facebook's official line is that calling this a breach is "completely false," since the people who signed up for Kogan's app did so willingly. As a result, that the information gained through those app logins was obtained within the scope of Facebook's guidelines. In other words, despite how shady all of this seems, the system worked exactly the way it was supposed to. The breakdown happened later when Kogan broke Facebook's rules and provided that information to Cambridge Analytica.

What has Facebook done about all this?

When all of this went down, very little -- in public, anyway. In a statement in its online newsroom, Facebook admits that it learned about Kogan and Cambridge Analytica's "violation" in 2015 and "demanded certifications from Kogan and all parties he had given data to that the information had been destroyed." As it turns out, some of that personal data might not have been deleted after all -- Facebook says it is "aggressively" trying to determine whether that's true.

More troubling is the fact that, as noted by Guardian reporter Carole Cadwalladr in an interview with CBS, Facebook never contacted any of the users involved. (She also added that Facebook took threatened to sue The Guardian to prevent an exposé from being published, which obviously isn't a good look.) Facebook VR/AR VP Andrew "Boz" Bosworth posted a rough timeline of the events (along with answers to certain FB-centric questions) earlier today, and it seems likely that timeline will remain a point of focus as investigations continue.

Finally, on March 16, a day before many of the biggest Cambridge Analytica stories broke, Facebook suspended accounts belonging to CA and its parent firm. The move is widely read as an attempt on Facebook's part to clean up some of the mess before The Guardian and The New York Times ran their most damning reports. Then, in a somewhat unexpected move, Facebook also disabled Christopher Wylie's account and prevented him from using Whatsapp, the popular messaging app Facebook acquired in 2014. (Consider this a brief reminder of how much of your social world Facebook currently owns.)

Beyond that, some Facebook execs spent the weekend asserting that there was no actual data breach. Meanwhile, CEO Mark Zuckerberg hasn't said anything about the unfolding situation, though we can imagine his silence can't last for too much longer.

So what happens now?

Scrutiny, and lots of it. Now that all of this is out in the open, powerful people are taking an interest. On March 18, Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-Minnesota) tweeted that Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg should testify in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee, adding that "it's clear these platforms can't police themselves." Senator Ron Wyden (D-Oregon) sent a letter (PDF) to Zuckerberg the following day, requesting information like the number of times similar incidents have occurred within the past ten years and whether Facebook has ever notified "individual users about inappropriate collection, retention or subsequent use of their data by third parties."

Facebook breach: This is a major breach that must be investigated. It's clear these platforms can't police themselves. I've called for more transparency & accountability for online political ads. They say "trust us." Mark Zuckerberg needs to testify before Senate Judiciary.

— Amy Klobuchar (@amyklobuchar) March 17, 2018

Meanwhile, in the UK, Cambridge Analytica CEO Alexander Nix recently told the Parliament's Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee that the company did not collect people's personal information through Facebook without consent. Since Nix lied, Committee chairman Damian Collins has accused the CEO of peddling false statements and has called CA whistleblower Christopher Wylie to offer evidence to parliament. Even more promising, UK Information Commissioner Elizabeth Denham confirmed that she is seeking a warrant to access Cambridge Analytica's servers.

BREAKING: Damian Collins, chair of UK parliament's news inquiry, has called Cambridge Analytica whistleblower @chrisinsilico to give evidence next week to parliament. I predict: fireworks.

— Carole Cadwalladr (@carolecadwalla) March 19, 2018

And as far as Facebook is concerned, there are few people more powerful than its shareholders. We wouldn't be surprised to see Facebook's financials bounce around for a while, too -- as I write this, the company's share price is down nearly 7 percent, shaving billions of dollars off Facebook's market cap (and eating away at Zuckerberg's net worth.) The entire core of its business is built on a foundation of trust with its users, and incidents like this can do serious damage to that trust.

This is scary -- should I keep using Facebook?

Honestly, you should at least give serious consideration to deleting your account. If you're a Facebook user, then you and all of your Facebooking friends are collectively the single most valuable thing the company has. Its fortunes rise and fall when its user numbers ebb and flow. The old internet adage says "if you're not paying, you're the product," and this is a perfect example of that.

The data we offer Facebook freely is a commodity to be accessed, mashed up, scraped and targeted against. For some, the value of the platform is enough to override the dangers. There's nothing wrong with that, and it's worth taking a few minutes to dig into account's privacy, app and ad settings to limit the amount of data you unknowingly offer to the machine. But there's also nothing wrong with saying enough is enough. None of us will cough up a cent to get bombarded by fake news, inane quizzes and game requests. But that doesn't mean we aren't paying for Facebook.