How 5G makes use of millimeter waves

Why are these waves crucial to the next generation of cellular internet?

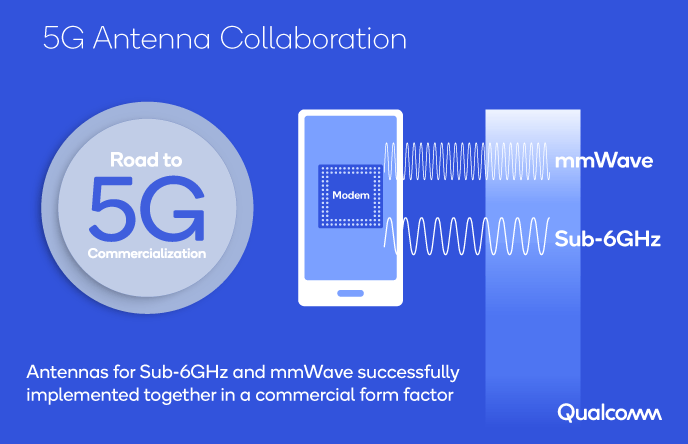

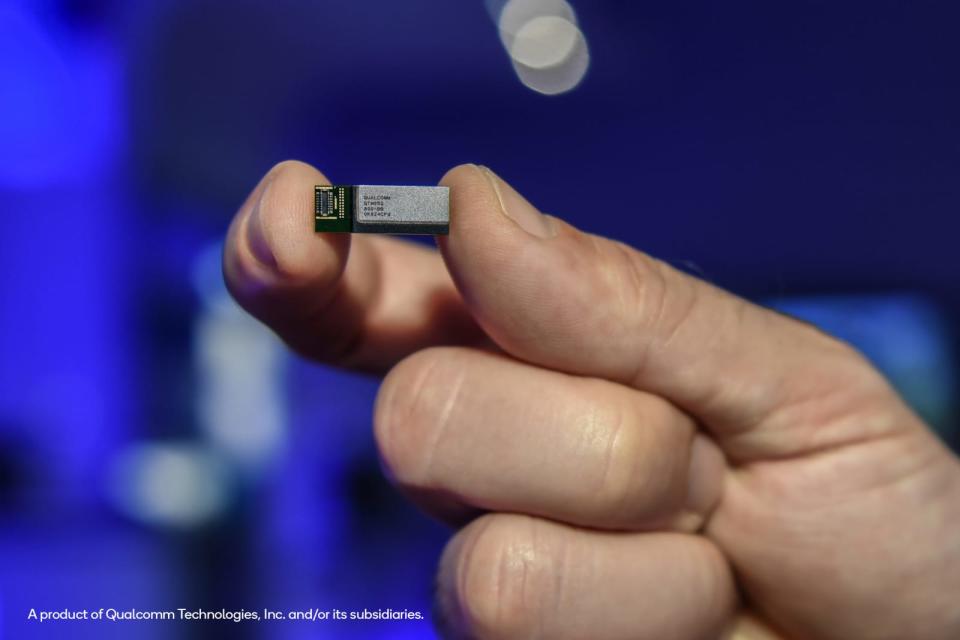

It took a while, but the first ever 5G spec was finally approved late last year. 5G NR, as it's called, will bring about super fast mobile internet by tapping into new spectrum. We're expecting to see the first 5G-ready phones in the first half of 2019, although most people likely won't experience the full benefits of the new technology until about a year later. Still, 5G NR promises to dramatically improve cellular internet speeds and enable experiences like always connected laptops or livestreaming from VR headsets. The entire mobile industry is excited as hell for it, so here's a little guide to help you make sense of the hype. 5G refers to the fifth generation of mobile networking standards determined by the 3GPP, the organization that sets the guidelines for every company operating in cellular communications. The official name, 5G NR, stands for New Radio, and doesn't really mean anything. It'll be used the way "LTE" is today, to differentiate it from previous versions. Where 3G brought the internet everywhere and 4G LTE made it faster, 5G NR is meant to vastly boost both the capacity and speed of networks, bringing you your high-res cat videos and 4K VR livestreams without delay. One of the ways 5G will enable this is by tapping into new, unused bands at the top of the radio spectrum. These high bands are known as millimeter waves (mmwaves), and have been recently been opened up by regulators for licensing. They've largely been untouched by the public, since the equipment required to use them effectively has typically been expensive and inaccessible. But technology has improved to the point where the industry collectively believes we can start tapping them for consumer electronics. And since they haven't been used for much, compared to lower bands, they're far less congested and can therefore enable super fast transfers. Qualcomm said you can expect "typical speeds" of 1.4 Gbps -- that's twenty times faster than the average US home broadband connection. At peak rates, think 5 Gbps, it's enough to stream more than 50 4K movies from Netflix at the same time. Millimeter waves tend to be susceptible to interference and generally need to maintain line-of-sight for transmission to work. At the most basic level, mmwave transmissions usually go in a straight line between point A and point B. But something as simple as a person walking in between the receiver and transmitter can block the signal altogether. So companies have to figure out how to make sure the signal gets from base stations to mobile devices, and with 5G NR, part of the solution are two processes called beamforming and beamtracking. In the most simple scenario for beamforming, where the biggest challenge is that the receiver isn't facing the transmitter, the solution is as simple as bouncing the beam off a surface at a precise angle. The receiving device uses beam tracking to determine which signal is the strongest and picks it up. That sounds straightforward, until you consider the challenges when implementing this in the real world -- like in an office building. Even when you have base stations set up on your floor, there are many variables to consider. For instance, metals bounce beams, while concrete absorbs them. So if you're inside a conference room, a base station from outside could potentially shoot a beam in through a hollow wall, hit a metal lamp and bounce off to your phone. To get this to work reliably enough for public use, there have to be a ton of beams for your phone to track. Not only that, your phone's antenna array has to be built in a way that your hand doesn't completely cover up the receiver at any time. Qualcomm's solution is to stash tiny antenna arrays in various corners of your phone, and is working with many major smartphone brands on where to place them. If you're not convinced that mmwaves will be stable enough when 5G first rolls out, don't fret. Just as your phone falls back to 3G when LTE isn't available, 4G will stick around to make sure you remain connected to the internet even if you're not using mmwaves. Most people won't have access to 5G immediately anyway -- the rollout is likely to begin in cities and spread out to rural areas, and you may need an expensive, high-end device to tap the new technology at first. Later versions of 5G will also allow things like IoT devices to connect to mmwaves, as well as allow for use of unlicensed spectrum to increase speeds some more. But eventually, it should become as prevalent as 4G is today. When that happens, what a world it will be.