Petit Depotto, 'Gnosia' and the new, obsolete game

It’s 2020 and people are still making games for the Vita and Dreamcast.

Epic has been basking in the limelight for its Unreal Engine 5 demo, and the console on everyone’s minds right now is Sony’s PlayStation 5. Like most of tech culture, the mainstream gaming industry is constantly hungry for next-gen hardware, and for major studios like Epic Games, Blizzard and Ubisoft, there’s an ongoing competition to stay ahead.

Yet despite the technophilia that defines modern video games, some indie developers still embrace the old.

Last June, a small Japanese indie studio named Petit Depotto unveiled Gnosia -- a werewolf-style role-playing adventure -- on the aging PlayStation Vita, which Sony officially discontinued in March 2019. Adapted from the 1986 Russian social game Mafia, werewolf scenarios require ‘villagers’ to deduce the identity of a ‘werewolf’ hiding among them.

“I tried playing a ‘werewolf’-type mobile game and was pretty dissatisfied with the experience,” said Shigoto, Petit Depotto’s narrative designer, who only wanted to be identified by a nickname, the Japanese word for “work.” “Gnosia came about because we wanted to play our ‘ideal’ werewolf-simulation game.” With the exception of Petit Depotto’s producer and director Toru Kawakatsu, the rest of the four-person team declined to provide their full names out of privacy.

But releasing on an obsolete device wasn’t always the plan. Work on Gnosia began in 2015, the same year that Sony stopped making Vita games. “At the beginning, we didn’t even consider it,” admitted Kawakatsu.

According to Shigoto, Gnosia was initially developed for Playstation Mobile, Sony’s now-defunct platform for the Vita and Android smartphones. “I had actually finished the PS Vita port when Playstation Mobile was shut down, so there was really no other option,” he said. But launching on an old handheld -- albeit with a cult following -- actually helped the game stand out.

Gnosia on the Vita was a hit. IGN Japan gave it a perfect 10/10 score. Then, Petit Depotto landed a coveted spot on the March 2020 Nintendo Direct livestreamed showcase before Gnosia hit Japan’s Nintendo Switch e-store in late April. It was a tremendous win for the tiny Nagoya-based team.

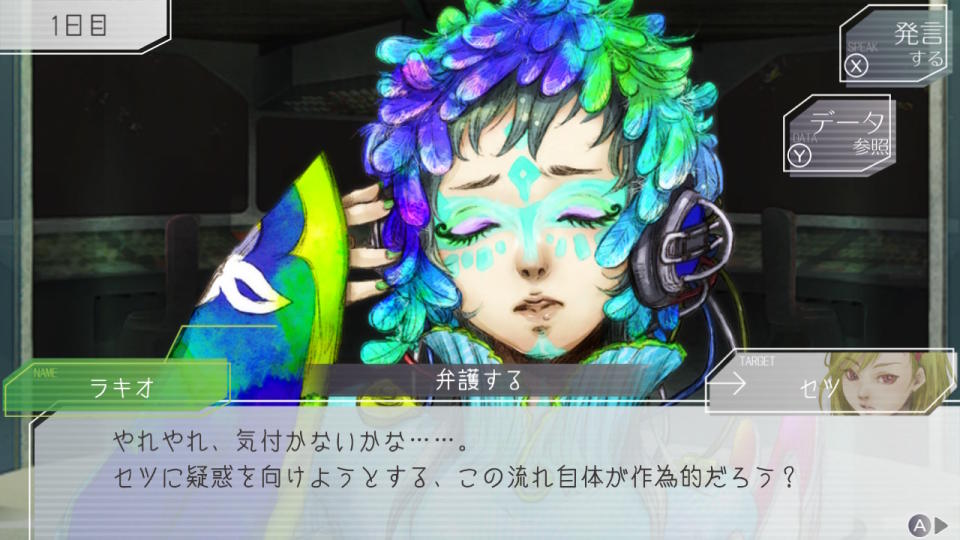

Part visual novel and part role-playing game, Gnosia expands on the simple werewolf format through layers of complex elements like time loops, compelling non-playable characters, skill systems, verbal boss fights and different character classes.

It blends familiar mechanics seen in games like Minit (where players have one minute of time for each playthrough), The Complex (where players must build trust with others) and the award-winning Disco Elysium (an existential detective game where dynamic dialogue and emotion drive the story). Petit Depotto brought new dimensions to a tried-and-tested party-game narrative while Gnosia’s time-loop feature gave the game replayability. The game was a breath of fresh air to an otherwise monotonous genre.

But Gnosia isn’t alone. The Vita community, which patiently waited for Gnosia and whose enthusiastic response helped Petit Depotto grab Nintendo’s attention, is one small part of a vast, decades-old retro-game-fandom scene that keeps near-obsolete consoles alive.

Kawakatsu believes it is an “honor” to launch games for these storied consoles. It takes a village to raise a child, but also to extend the lifespan of a beloved elder.

The Vita is far from the oldest platform pushing past its expiration date. Avid communities are devoted to the 38-year-old Commodore 64, 40-year-old Atari machines, almost every Sega console and Nintendo’s 3DS and Game Boys. Console gamers bond deeply with the idiosyncrasies of each device, each with its own specs and technical limitations.

“You are assured that everybody else who owns one shares the essentially same experience as you, that the machine is gonna perform the same way, that the games are exactly the same, the sounds are the same,” said Jason Scott, a tech historian who works at the Internet Archive. “So there’s a real strong sense of community among people who own a certain platform … even the console makers, I don’t think, 100 percent understand how cohesive that made these communities.”

There’s also nostalgia. “To understand that somebody going through a certain age thinks this console is part of their childhood or part of their life means that the lasting effects of it ends up being as meaningful as having come from a certain town or having gone to a certain school,” Scott continued.

In 2010, retro gaming company Watermelon released an original 16-bit role-playing game called Pier Solar and the Great Architects for the Sega Genesis (also known as the Mega Drive), which was discontinued in 1999 and is remembered as Sega’s most popular machine.

The game began as a project on Eidolon’s Inn, a now-defunct forum for old-school Sega enthusiasts, and was subsequently rereleased on the Dreamcast in 2015, 14 years after Sega’s final console was axed.

Watermelon went on to make Paprium, another Genesis title designed to be played on the original hardware. Other speciality studios like Big Evil Corporation continue work on retro projects: In 2015 the UK company crowdfunded a new Genesis game, Tanglewood, and it’s currently working on The Alexandra Project. Meanwhile, in 2020, people are still making games for the Dreamcast.

But playing on old platforms means keeping them alive in a neophilic world that fetishizes upgrades. Retro gamers and niche developers maintain the hardware needed to play these games, while professional archivists help DIYers with everything from networking and troubleshooting to digging up technical documentation.

Based in Oakland, California, Frank Cifaldi is the co-founder of the Video Game History Foundation and has made it his life’s work to preserve video game culture. The foundation’s mission includes documenting how video games are being played and finding alternative ways to preserve them. Companies like Analogue and Sega have followed this trend, fine-tuning emulators and homage hardware to replicate playing on original machines. Of course, for some purists, emulators simply won’t do -- only the original console.

“Ninety-nine point nine percent of video game preservation is happening in the fan communities. It’s not happening with organizations like ours,” Cifaldi explained. “They're the ones who are figuring out replacement parts when things go bad; they’re the ones figuring out how to modify these old systems to put out better video signals so that we can capture them better; they’re the ones who are figuring out how to replace the CD drive in old consoles so we can read games off an SD card instead.”

Game companies aren’t often helpful in grassroots restoration projects. But Cifaldi recalled an incident in 2016 when Nintendo -- usually known for cease and desists rather than community outreach -- allowed access to an incredibly rare artefact.

“[Nintendo of America] still had an intact arcade cabinet … for a game that they tested in the United States -- and it failed, so it never went into manufacturing -- called Sky Skipper,” he said. “And they actually let someone in the preservation community come and take photographs and scan the artwork and stuff like that from that cabinet.” In 2017, fans managed to rebuild this singular piece of arcade history.

While not all retro gamers focus on the posteric significance of these relics, preservation is a vital part of fan enthusiasm. “I often forget that one form of preservation is preserving interest in something,” Cifaldi mused.

In his experience, this can vary according to different cultural contexts. For instance, much enthusiasm for Japan’s old games and gaming systems has come from outside the country. “In Japan … the copyright laws are much more strict, and also I suspect because of that, there’s what I would call a cultural aversion to sharing a creator’s works without them being 100 percent on board with it,” he said.

Japan’s NPO Game Preservation Society is one such organization trying to archive and protect the country’s rich cultural legacy in video games. Efforts to document and save rare Japan-only releases will face an even greater challenge, and one day, this might include Gnosia. In the future, perhaps Gnosia’s first port on the Vita will become an object of curiosity for retro hobbyists.

When asked how Japanese Vita fans reacted to the Gnosia launch announcement, Shigoto said, “I don’t think anyone made a big deal out of it.” But Kawakatsu cited a responsibility not to disappoint Vita fans. “We wanted to release the game while the PS Vita was still active in the market,” he said. “However, due to the time spent on development, we could only ship it after the PS Vita was phased out.”

Even after its retirement, the Vita -- which was seen as a commercial flop -- has retained a curiously strong fan base. Sony introduced the Vita in 2011, a follow-up to the PlayStation Portable in an era when people were increasingly buying smartphones.

With its rounded corners, pleasantly clicky buttons and large OLED screen, the Vita was Sony’s final attempt to make handhelds happen while competing against the Nintendo 3DS. In many ways, the Vita can be considered an ancestor to the Switch, so much so that indie Switch developers continue to have a particular fondness for their common design DNA.

Retro indie developer Brian Provinciano left a full-time job to go all in on his passion for retro games. “It’s not about porting these games to every platform I can. That’s never been my goal,” he said via email. “I usually choose platforms that have a sentimental value, or present a unique architectural challenge. Every port usually begins from a moment of curiosity. I’ll look at a system and ask, ‘Hmm … I wonder if I could get it running on that?’” (The answer is almost always yes.)

Provinciano made the original titles Retro City Rampage and Shakedown: Hawaii -- loving spoofs of early Grand Theft Auto games -- both of which were ported to the Vita.

Provinciano considers the Vita the “pinnacle” of handheld consoles. “It was the perfect form factor -- the screen was large, but not so large as to make the system unwieldy. It had two sticks and the buttons worked well. The system was powerful, and the development tools were incredibly easy to use.” Today, he’s working on ports of his games for the Nintendo Wii and Wii U.

But even with today’s improvements in processing and graphics, Proviniciano yearns for something a little simpler. “As much as I do love the Switch, I’m still crossing my fingers that Nintendo will one day release a Switch Lite-Lite, with the same form factor as the PS Vita,” he said.

Shigoto plays both the Vita and Switch. “I feel that both are great for text-heavy/text-based games,” he said. Petit Depotto art designer Cotori, who also preferred to use a pseudonym, agreed. When Petit Depotto began work on Gnosia, the Vita was still the ideal platform for text-based adventures. “I think that the Nintendo Switch has now become that system. There aren’t any other ‘active’ mobile game systems around,” said Cotori, referring to the Switch’s ability to seamlessly transition from a TV-based console to a handheld.

Today, the Vita is best remembered for its eclectic library of visual novels, indie titles and niche Japanese games -- the kind of content that shines on the Switch. And while Gnosia may be in the spotlight with its Vita-to-Switch success, people are still churning out games for the Vita on the PlayStation store.

Gnosia was originally intended to be a romance simulation game -- a fitting parallel to the profound relationships and lifelong commitments that people have with old consoles. Said Cotori: “Isn’t the whole notion of ‘wanting to make it to the end’ with someone in werewolf and ‘death games’ a completely romantic situation?”