Necessary violence: The creators of The Last of Us defend its reliance on combat

PlayStation 3 exclusive The Last of Us was the most successful game of 2013. That's not just sales (it sold extremely well, to the tune of 3.4 million in its first three weeks), but also critical reception (an average Metacritic score of 95/100 and it swept game of the year awards across the game industry in 2013). Last week, The Last of Us earned development studio Naughty Dog a whopping 10 wins at the annual DICE awards show in Las Vegas -- considered the Oscars of gaming.

With Naughty Dog's past creating hit franchises like Crash Bandicoot, Jak & Daxter and Uncharted, The Last of Us leads Neil Druckmann and Bruce Straley aren't strangers to success (these guys led development of Uncharted 2, another extremely successful game). Their latest work is a tremendous departure.

Critics drudge up vocabulary to describe The Last of Us that's rarely used in game criticism: "emotionally grueling," "I wanted to fight for them." Beyond just being a thoughtfully told story in a video game, The Last of Us takes a bold step in largely skipping combat. Most encounters can be outright ignored, traded for tension while the game's two main characters (Joel and Ellie) slip past "infected" or, worse, the terrible other human beings in the post-apocalyptic future. The Last of Us is the rare triple-A game that dares to be emotionally engaging and eschew violence as the only form of gameplay.

"We were unsure if people would get into it or not," Druckmann told us in an interview last week. We'd asked about the cinematic moments -- the giraffe scene, that gut-wrenching ending -- and why Naughty Dog had bothered with so many combat scenarios in such a story-focused, risky game. "We were pleasantly surprised to see that people are very much into it."

In fact, the criticism heard most loudly by the TLOU team specifically focused on combat: too much, too often, and too arduous. "For ourselves, compared to previous games we've made, this has way fewer encounters, and those encounters you fight way fewer enemies," Druckmann said. That reticence to move away from combat isn't unique to Naughty Dog, though -- the majority of so-called "triple-A" games feature combat as the primary interaction (last year's holiday hits, for instance: Call of Duty, Assassin's Creed, Battlefield, etc.).

The Last of Us -- though bold in many ways -- still featured combat as the primary interaction. Rather than focusing on combat as a means to achieve objectives, it was more a necessary evil to lead the game's fragile protagonist duo to safety. "A lot of developers, not just triple-A, but a lot of developers do use combat as a crutch," Straley told us. He defended its use in TLOU, however, as a vehicle for contrast against the game's emotionally resonant moments. "The contrast for us is more about trying to balance the two so that you have both ends of the spectrum, because you have to have the dark to have the light."

Would The Last of Us work without combat? Perhaps, Druckmann said, but it'd have to tell a different story. "Say you wanted to tell a story about an archaeologist that doesn't involve Nazis. As soon as you have conflict, where someone's taking out the guns trying to kill you, then as people you would rise to that conflict," he said, in reference to Indiana Jones. He argued that we accept the fantasy of that world (and the murderous protagonist who comes with it), and the same happens in games: Nathan Drake is acceptable in Uncharted because he's built into a world where Nathan Drake makes sense.

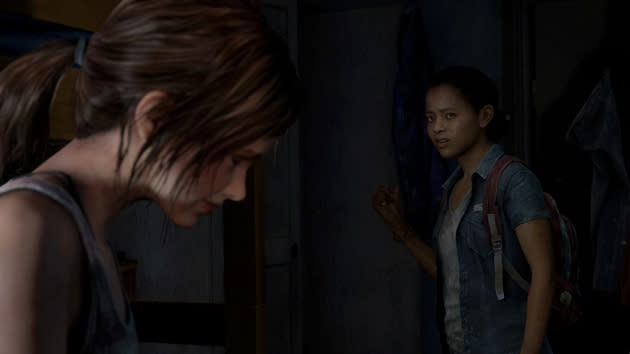

Given the response to TLOU from players and critics alike, Druckmann and Straley explored the possibility of throwing away combat altogether in the game's final playable addition: a side story prequel featuring Ellie and a new character, titled "Left Behind" (available this week). In the end, they decided against that, though the Left Behind addition features even less combat than the main game. Druckmann explained:

"What if there were no infected in this game? What if there was no combat at all in this additional chapter? And we feel like we would lose something that's really integral to The Last of Us, which is that contrast. The giraffe sequence works because of all the horrible things you've done and experienced in the Winter section. Otherwise I think the giraffe sequence would feel pretty flat without the surrounding bits to it. The ending works well because, as Joel, you've done really horrible things in that hospital. Maybe we could argue about the number of encounters, or how many enemies should've been in the hospital, but we definitely feel strong that there should've been a fight, a kind of murdering spree to get to Ellie, because that says something about Joel and what he would do to save someone he loves. Because ultimately that's what those arcs of the character were: how far they were willing to go to save someone they really care for."

Though TLOU is finished (read: no sequels, no more DLC -- Naughty Dog's calling it one and done), the lessons learned in the process are far reaching. "We have to check in with ourselves as developers and figure out what are we after here," Straley told us. Will the next Naughty Dog game still feature combat as the main form of interaction? Perhaps; it all depends on the story that the team wants to tell. "As long as we're still flexible to check in on what we think is acceptable and what kind of stories and experiences we want to deliver, then we'll constantly push ourselves. And that's exciting," he said. Like Naughty Dog, we can't predict if what they make next will be a success, but we sure do want to play it -- whatever it is.