What you need to know about online advertisers tracking you

Spend lots of time online? Then perhaps you've heard of targeted advertising, "Big Data" analysis and complaints of privacy violations by advertising companies. The ads above your Gmail inbox? Yeah, those. As it turns out, most people don't like being tracked by advertisers. Surprise! As such, a variety of tools exist to protect individuals. But what about a solution that anyone could use, that didn't require knowledge of cryptography or even a software install? That's where the Do Not Track initiative comes in.

Do Not Track (DNT) is explained by its own name: Don't track what I do online, including what I buy, what I read, what I say and who I communicate with. But how should it work? Therein lies the controversy. Since the subject is still being debated, now's the perfect time to learn about it, voice your opinion and request more control over your data. If you want more control, that is.

What is it?

The idea of Do Not Track (DNT) was initially conceived in late 2007. Several groups, including the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT) and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), asked the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to help with the creation of something similar to the National Do Not Call Registry: a system to limit the amount of personally identifiable information a company can obtain without express authorization from an individual. More directly, DNT is a system to protect individuals from advertisers eager for personal info on consumers.

The proposed technology asked for online advertisers to submit web address information to the FTC, which the agency would publish and make accessible to the public. Why a list? So that web browsers (Firefox, Safari, Internet Explorer, etc.) could effectively block advertiser tracking on a wide scale. The list concept, however, was ultimately flawed: Every time an advertiser changed its web info, the DNT function became obsolete. It would require extreme vigilance to keep the system 100 percent effective. As such, it died.

In 2010, the idea of Do Not Track came back to life, albeit in a completely different form. Instead of relying on a list, web browsers would simply ask the advertising software (instantly, in the time it takes to load a webpage) to not track personal information. This is the Do Not Track initiative as we know it today.

Why should I care?

If you don't care that websites and companies monitor your behavior, share what they know about you and generally act creepy about personal information, well, we're impressed you got this far into a piece about Do Not Track. If you don't want Amazon to show you ads about swimsuits, towels and sunblock because you mentioned you were excited about going to the beach on Facebook, you should care.

Not freaked out enough by that example? What if they know your daughter is pregnant before you know? For some people, this isn't a big deal. For others, it's extremely important.

We aren't going to get into the implications of governments knowing everything about you; the Do Not Track initiative is only aimed at advertising companies. However, it's not crazy to think that a government could request all the data an advertising company has in order to collect taxes, or worse: infringe on free-speech rights.

How does it work?

Modern browsers, such as Firefox, currently send something called "headers" to web servers (computers where websites are hosted). Say you're visiting, I don't know, this website. Say you're on a PC, running Windows 7, and you're using Firefox to read all about whatever happened to Netscape. The server hosting Engadget's content needs to know how to present information (in this case, our website), to your particular setup. So your computer tells our web server how it's set up and in turn, our web server returns a readable website. It also returns ad-tracking software.

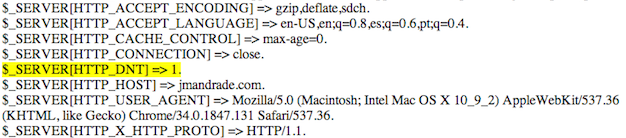

The Do Not Track initiative simply adds an additional piece of information (the DNT header) to the initial request, which is set to 0 or 1. If the DNT header equals 1, the web browser knows it should not track the user's behavior on the site, and a company knows not to use that data for advertising purposes.

You can see the DNT header turned on in the highlighted text below:

Most popular web browsers and at least the two most popular web servers (IIS and Apache) already offer support for Do Not Track. To enable this option on your browser of choice, just follow the steps dictated by the developers, linked below:

Firefox

Internet Explorer

Safari

Chrome

Opera

Can I start using it right now?

Yes -- but not so fast, cowpoke. While the system is implemented in browsers and web servers, it's not actually being used by advertising companies right now. A list of websites that honor the system is on donottrack.us, but not all advertising companies have agreed to abide by it. There are even conflicts between browser and web server developers as to how it should be used.

For example: Google, one of the biggest advertising companies on the internet, provides a warning about the Do Not Track setting in Chrome (seen below). Not exactly reassuring, is it?

What's the argument?

One major point of contention is a concept known as "the tyranny of the default." This idea is that a great majority of users never change the default settings, and thus, whatever the default settings were will most likely stay that way. Should browsers assume that users want DNT enabled by default? Microsoft thought so, and proceeded to enable DNT on Internet Explorer without user interaction. However, many believe that in order for the initiative to have any type of weight on advertising companies, the user should intentionally enable it.

Because of Microsoft's decision to enable DNT by default in IE, the people behind the Apache web server patched out the setting. Wait, what? You see, according to the rules of DNT, the service can only be implemented if it "reflect[s] the user's preference, not the choice of some vendor, institution or network-imposed mechanism outside the user's control." If there is "misuse" of the technology -- such as Microsoft, an institution, turning it on by default -- web servers can decide to ignore the header and the tool is useless.

The debate about enabling DNT by default started in 2012 and it hasn't ended yet. Google, Facebook and now Yahoo all ignore DNT requests (at least for now).

Want even more?

Everything about Do Not Track is still open for debate. Technology companies are still discussing proper ways to implement it. Advertising companies are deciding if they want to respect it. There's an ongoing debate as to whether DNT means "don't save this information" or "don't use this information." And, of course, governments are considering enforcing the technology. This means that, as of right now, DNT is useless.

For now, the best you can do is precisely what you've already done by reading this article: Learn about Do Not Track. If you do want this technology or something that serves a similar purpose, be vocal about it. Take it directly to advertising companies on social networks. Contacting your senator wouldn't hurt either! Maybe you love the benefits of targeted advertising and personalized web browsing? Express your opinion and let people know! The subject is still wide open for debate.