Long range, low power sensors may lead to better health wearables

They could also improve farming and environmental data collection.

For small electronic devices and sensors like those found in wearables that can decipher biological information from sweat and contact lenses that can measure glucose levels, there are a couple of trade offs that limit their function. In order to be small and unobtrusive, they need to run on very little power. Otherwise, they require large batteries. But reduced power requirements also tend to limit how far these devices can send their signals, many of which have to be within a few feet of their receivers. But researchers at the University of Washington have overcome the need to compromise on communication distances and they presented the work today at UbiComp 2017.

"Until now, devices that can communicate over long distances have consumed a lot of power. The trade off in a low-power device that consumes microwatts of power is that its communication range is short," Shyam Gollakota, an author of the paper, said in a statement. "Now we've shown that we can offer both, which will be pretty game-changing for a lot of different industries and applications."

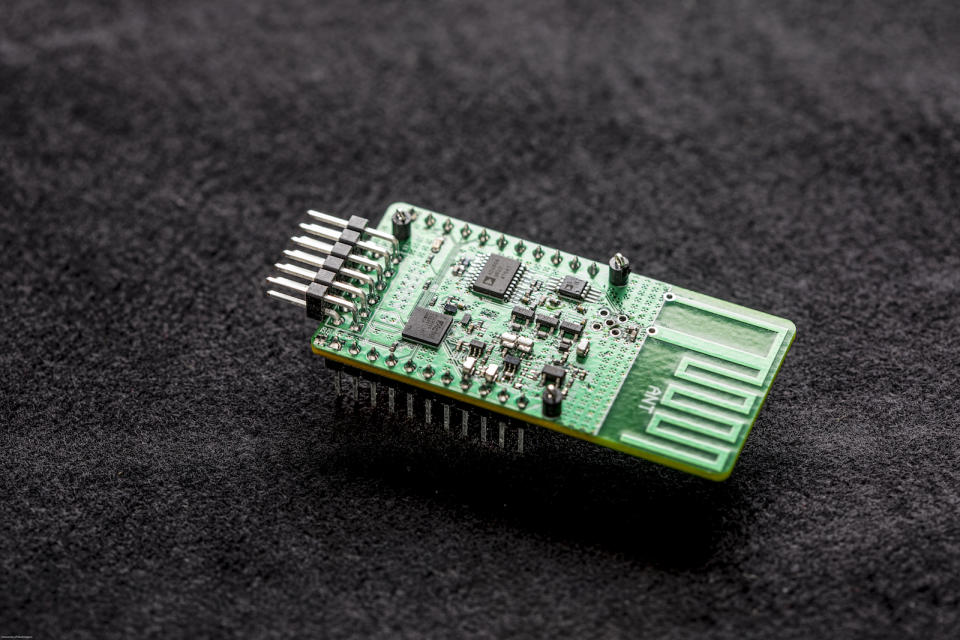

The team's system is made up of three devices -- one that emits a radio signal, sensors that can shove information into reflections of that signal and a receiver that can decode that information. And the innovation is in how they transmit those initial signals -- spreading them across a range of frequencies. They show with this setup that their sensors can transmit data across a house, throughout an office area with 41 rooms and across an acre of farmland. They even put the sensors to work within a contact lens and in a patch that attached to the skin. They found they could reliably get signals from those sensors across a large room and a 3,328 square-foot atrium. The sensors use 1,000 times less power than similar current technologies and can be produced for 10 to 20 cents each. Further, because they designed the system to work with off-the-shelf receivers, that component remains inexpensive as well.

In theory, these sensors could be used to detect soil moisture across a plot of farmland or pollution in a city as well as in a number of biological- and health-related applications. The team is commercializing the system and hopes to have it ready for sale next spring.