Trump's gutted EPA might lead to 80,000 more deaths per decade

Two Harvard scientists estimate that relaxed protections will be lethal for some.

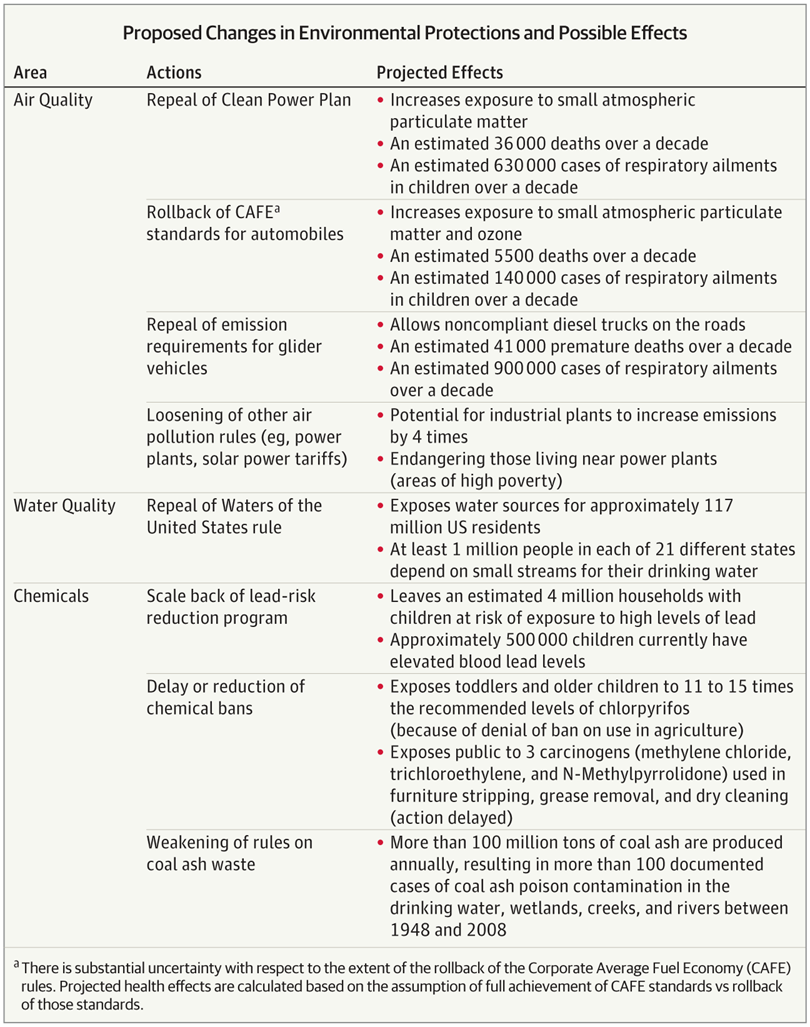

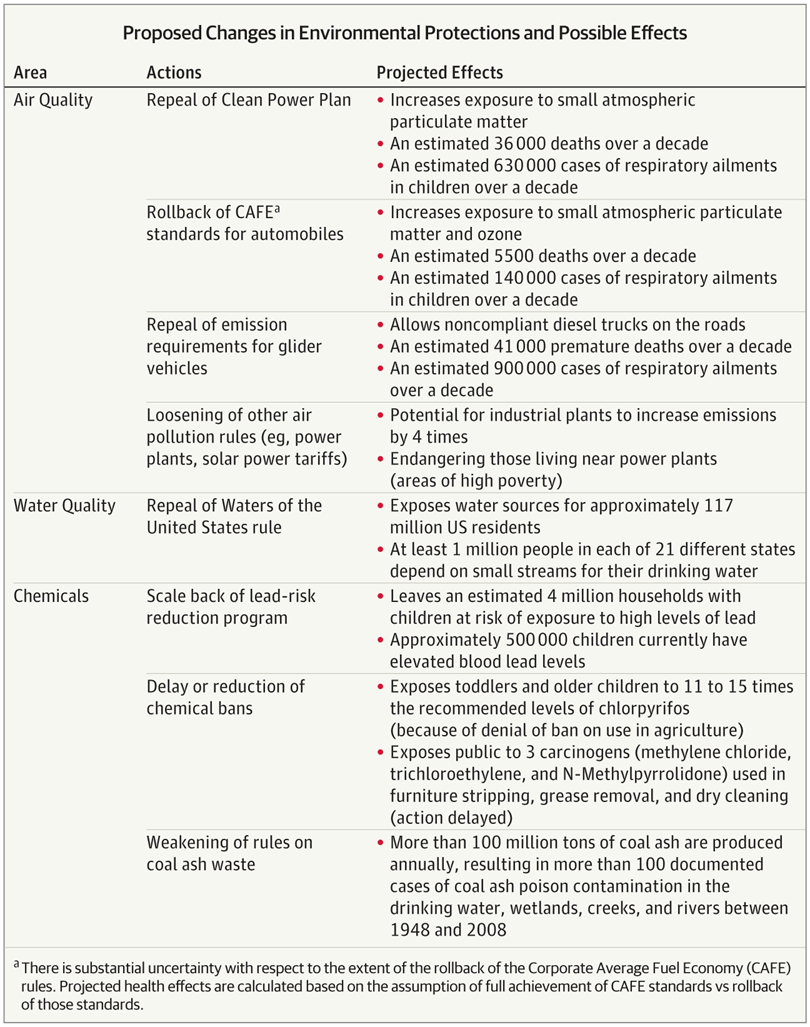

Since the moment Trump entered office in January 2017, government-mandated environmental protections have been on the chopping block. Now we have an estimate for how many more people might die when some are repealed. According to two Harvard scientists, changes proposed or in process to EPA policies will lead to over 80,000 additional deaths over the next decade -- and respiratory problems for over a million people.

Changes in air quality will cause the most consequences to public health, the two Harvard researchers, economist David Cutler and biostatistician Francesca Dominici, stated in an online essay in the JAMA Forum. It's key to point out that the numbers they cited are on the upper end of the estimate ranges. For example, repealing Obama's signature Clean Power Plan alone would lead to an estimated 36,000 deaths and 630,000 cases of respiratory infection in kids in the next decade, according to the EPA's impact analysis when the CPP was implemented, which anticipated a range of additional deaths between 1500-3600.

While it's on the higher end of estimates, the essay tabulates a holistic and science-backed guess at the additional deaths resulting from changes to weakening environmental protections across the board. Rolling back the CAFE standards for autos, for instance, would lead to another 5500 deaths and 140,000 cases of respiratory ailments in children. Other policy changes will expose water sources to higher levels of lead and chemicals, including carcinogens.

The EPA, run by Trump-appointed climate change skeptic Scott Pruitt, dismissed the essay in comment to Bloomberg: "This is not a scientific article, it's a political article." The JAMA Forum publishes essays from experts within the scientific community, not scientific studies, but co-author Cutler defended the piece, stating that it's backed up by the EPA's own regulatory impact analyses. "If they don't like what their scientists say, they should provide scientific reasons for thinking so," Cutler told Bloomberg.