Scientists design 'decoy platelets' that reduce risk of blood clots

And it could have a major impact on cancer therapies, too.

Heart disease, stroke, sepsis and cancer are incredibly serious conditions which together cause the greatest number of deaths around the world. They're unique illnesses, but they have something in common -- they're all associated with activated platelets, which play an important role in healing, but for some can also contribute to dangerous blood clots and tumors. Now, scientists think they've found a way to mitigate the risks associated with these platelets, thereby "outsmarting" the catalyst for these diseases.

There are already a number of antiplatelet drugs on the market, but their effects are not easily reversible, which means patients are at risk of uncontrolled bleeding if injured. And if they need to undergo surgery for their condition, they have to stop treatment up to a week before their operation, which increases their risk of developing blood clots. But researchers at Harvard University have created a drug-free, reversible antiplatelet therapy that uses deactivated "decoy" platelets, which can be initiated and reversed immediately.

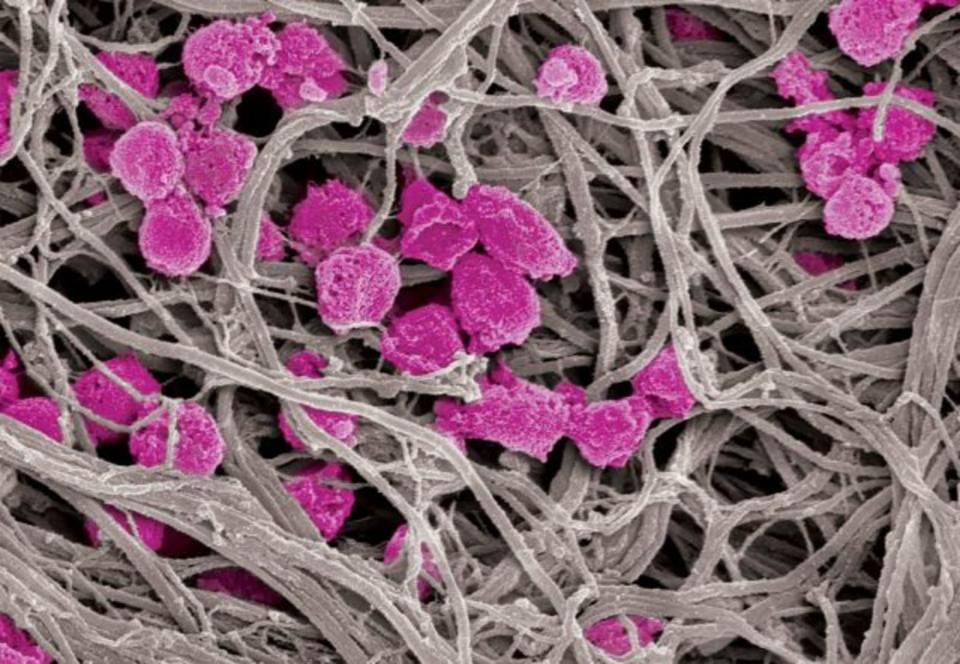

The decoys are made from existing human platelets which have been stripped clean via centrifugation and detergent, while retaining adhesive proteins on their surfaces. They bind to other cells that naturally occur in the bloodstream, but because they've been deactivated are unable to initiate the clotting process. So when they're added to normal human blood, the overall clotting process is essentially diluted, allowing normal healing processes to take place without the risk of excessive clotting.

As Anne-Laure Papa, the paper's first author, explains, "The decoys, unlike normal intact platelets, are unable to bind to the vessel wall and likely hinder the normal platelets' ability to bind as well. A way to imagine this would be that the decoys are fast-moving skaters skating along the wall of an ice rink, and their high speed prevents other skaters from getting to the wall, thus limiting them from slowing down and grabbing onto it."

The team also believes the therapy could play an important role in treatment for tumors. Platelets are known to bind to cancer cells, protecting them from the body's immune system and thereby helping them form new tumors. But the researchers found that by adding decoys along with normal platelets in microfluidic channels, the platelets were almost completely prevented from helping the cancer cells invade the channel wall, suggesting that they could prevent the formation of new tumors. Papa says it's possible that one day these decoys could be deployed during chemotherapy to prevent existing tumors from spreading, or new ones from forming.

So far, the therapy has only been tested on rabbits and mice, but the team is confident the results could be replicated in humans. Papa's lab is now working on ensuring the decoys can last longer in the bloodstream for enhanced effectiveness, and studying whether they can be loaded with drugs to help deliver therapies directly to the sites of blood clots and tumors, or possibly even kill circulating tumor cells in the bloodstream altogether.