How a Harvard class project changed barbecue

Using computer-based models to make cooking more efficient.

"A hundred inches of snow that winter, it was really quite terrible."

There are several factors to overcome when trying to cook a 14-pound slab of brisket during the winter. Not only do you have to contend with freezing temperatures but you also have to keep your grill or smoker from getting too wet with moisture from the snow. On top of that, you have to keep the fire going for several hours, or you've just wasted a pricey cut of beef.

Desora co-founder and CTO, Yinka Ogunbiyi, knows first-hand the challenges of "low-and-slow" barbecue in the dead of winter. Along with CEO, Michel Maalouly, Ogunbiyi spent hours in the cold every weekend attempting to perfect a grill design as part of an engineering course at Harvard in 2015. The goal was to outperform what many consider to be the pinnacle of backyard grilling and smoking machinery: The Big Green Egg.

"We were amateurs, smoking a brisket every week in the cold Boston snow," Ogunbiyi said.

There was another wrinkle to the assignment, though. Professor Kevin "Kit" Parker had arranged for the class to have a real client, and it was a legit one: popular kitchen retailer Williams-Sonoma. This meant there was potential for the final designs to become an actual product if they could offer something better than the grills available at the time could muster.

"Boston's worst winter on record made quick work of showing the faults and shortcomings of existing products," Maalouly explained. "We had been using the industry-leading smokers at the time and found the cooking experience to be severely lacking." The pair needed a way to maximize heat coverage, accelerate the process and enhance flavor if they were going to beat the Egg.

In addition to the overall cooking process, a lot of grills -- even in 2019 -- don't have a way for you to remotely monitor your meat unless you splurge for a more expensive model. Companies like Traeger, Rec-Tec, Green Mountain Grills and others allow you to keep tabs on things from your phone, but those are wood-pellet grills, and they aren't exactly cheap. Plus, they're electric, so it's not a huge leap to add WiFi connectivity when you already have a power source that regulates temperature. Ceramic grills, like the Big Green Egg, use charcoal or wood chunks to cook and flavor food, so remote control and monitoring is a little trickier, unless you have an additional device.

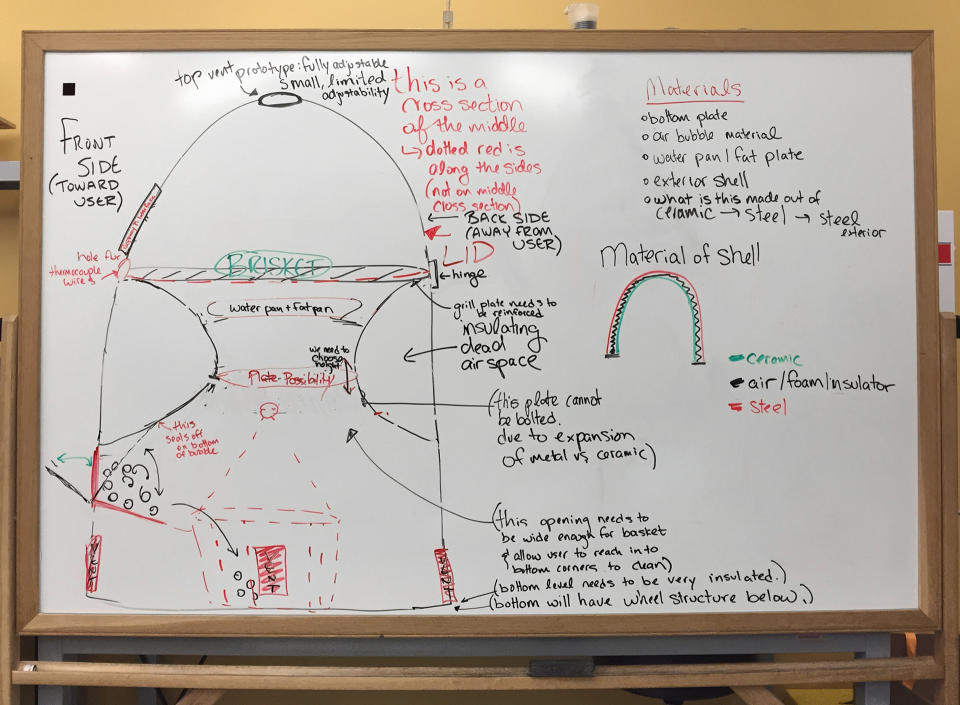

For Maalouly and Ogunbiyi, the ability to watch their long smoke sessions from indoors became a must. To ensure they were getting accurate data without having to venture into the Boston white-out, the pair created a mobile app that allowed them to monitor temperatures from the classroom. But the goal of the project was to enhance the overall process, which included making the cooking vessel itself as efficient as possible. Remote control was certainly part of that, but changes to the design of the grill itself would also achieve that goal.

They also realized they had another tool that would make their lives easier: computer models. A piece of software called ComFLOW helped them to simulate cooks without firing up a grill, buying pricey meat or, perhaps most importantly, venturing out into the deep freeze. Ogunbiyi explained that while ComFLOW is typically used for things like rockets, cars and chemical plants, you can also use it to analyze a grill.

"It's just basically figuring out where the heat is in your barbecue and where the smoke's going," she said. "You ended up studying all the physics and chemistry with barbecue and putting in these computer models."

The other benefit was speed. To cook a brisket on a grill or smoker, you typically need around 12 to 16 hours. When you employ computer models, Ogunbiyi explained, you can get a result in about an hour. The team eventually discovered that a hyperbolic or hour-glass shaped chamber, or an insert that altered a grill's shape, not only makes the Green Egg-style grills' heat distribution more efficient but it made the food taste better, too.

"We knew that the industry was quickly changing and that we had to move fast if we wanted to be a part of it," Maalouly recalled.

He and Ogunbiyi were on a mission. Within six months of graduating from Harvard, the duo had become Kansas City Barbeque Society (KCBS) certified judges. The non-profit organization sanctions hundreds of competitions around the world each year, and some regard it as the unofficial governing body of all things 'cue. Maalouly and Ogunbiyi saw certification as a requirement for anyone who wanted to start a barbecue company. Their engineering professor would also serve as chief creative officer.

During that time, they had also raised $1.5 million from Morningside Ventures, a Newton, MA,-based venture capital firm with close ties to the university. The funding allowed the team to take a key first step to establishing its company, Desora. The students were able to license the computer models and patent applications from the class project so the newly formed company could continue to test grills designs with software before building any prototypes. Now the pair was actually developing a product, saving time and money was a must.

"We drastically cut down the time it took to go from idea to mass market product by analytically benchmarking the performance of our grills before even prototyping them," Maalouly noted.

Around the same time as that first round of funding, Desora signed an exclusive licensing agreement with Harvard. The terms included Harvard taking an equity position in the company that spun out from one of its courses.

Maalouly and Ogunbiyi were on their way to achieving the potential they saw in their designs during class. They had built another prototype in a ceramics studio, but the two had a dilemma. The insert they created, the grill add-on that streamlined the cooking process and enhanced flavor, only worked with their grill. So if they turned it into a standalone product, they'd have to convince people to ditch whatever they already had and buy something new to use the results of years of research and analysis.

"We didn't want to go through that process of trying to convince people to sell their existing grill or completely do something new," Ogunbiyi recalled.

Within a few months, Desora was approached by Kamado Joe -- currently one of the biggest names in charcoal and ceramic grills. The company was founded by Bobby Brennan, a former GE executive who loved to cook with a ceramic grill. However, he recognized various ways he thought he could improve the overall experience, much like the Desora founders sought to do back at Harvard. A couple of Kamado Joe's early innovations include a hinge that makes it easier to lift the lid and an ash box that's much easier to clean.

"Because [Kamado Joe] started that way, we were always looking for partners that could help us with that mission," explained Cara Finger, Kamado Joe's chief marketing officer. "When you look at a class project and an industry that hasn't had a lot of data or innovation around its product, that fit so well with our mission and it was just a natural partnership."

Desora didn't have to create its own grills and try to market them. Its founders now had an established partner who wanted to leverage their research and technology to make its own products better. The company signed a licensing and joint development agreement with Kamado Joe, which would merge product lines from both sides. So far, Desora and Kamado Joe have co-created four products: three different grill models and a smart grill controller.

With the Classic III, Big Joe III and ProJoe grills, the partners employ the hyperbola-shaped chamber Maalouly and Ogunbiyi began perfecting at Harvard. It's now called the SlōRoller, but it still accelerates cooking, creates increased smoke exposure and distributes heat more efficiently. The SlōRoller ensures 85 percent of the cooking space in these grills remains within five degrees of each other. Indeed, the unique shape also reduces cook times by one to two hours thanks to its enhanced convection. The grills require an investment, ranging from $1,700 up to $3,700, but they aren't wildly expensive compared to much of the ceramic grill competition.

"All these product innovations, which are key in making the best barbecue, were made possible by the thousands of designs we had tested with our proprietary models," Maalouly explained.

The other product that Desora released with Kamado Joe is the iKamand, a smart grill controller that works with all three of the jointly developed models. Much like the monitoring setup Maalouly and Ogunbiyi built in class to keep them out of the cold, the iKamand monitors and controls a Kamado Joe grill remotely. It sends temperature updates every 20 seconds, so you know you're getting accurate, up-to-the-minute readings. The controller runs on Desora's custom software, which learns from anonymized cook parameters to improve the process for all users over time. The app that houses all of the features also includes recipes, video tips and more, so even beginners will have a place to start.

"It's a supplement to a product that's already got a lot of innovation -- it's just one more thing that improves your experience," Finger explained. She also noted that something Kamado Joe hears "a lot" from customers is that they like how the iKamand is an optional feature. If you want to go more traditional and enjoy the process, you can.

During the first week iKamand was on sale in June 2018, Desora and Kamado Joe sold over 1,000 units. That might not sound like a lot, but for a $249 add-on that only works with a few grills, and given the size of the Harvard-born company, it was seen internally as a major success.

This device isn't unique to Kamado Joe. You can buy a similar add-on for the Big Green Egg, and thermometer company Thermoworks offers a temperature control fan called Billows, which integrates with its heat and meat monitoring products. Still, Maalouly and Ogunbiyi had turned a key piece of a Harvard project into a commercial product.

At the end of Desora's first year in the market, Maalouly and Ogunbiyi believed it was time to expand the company beyond outdoor grilling and offer something people could use indoors. In November 2018, Desora acquired Cinder, a company that created a grill that uses temperature-sensing algorithms and other technology to cook food with "one-degree precision."

Algorithms, computer models and devices that get better over time. The pattern was apparent.

With the Cinder grill, you can set the temperature on a steak and go about your business. The device will grill it to the exact temperature without a thermometer or probe, and it alerts you when your food is ready. It also gives you time estimates based on those algorithms that drive the cooking process. Maalouly says that if you wanted to, you could leave the grill unattended for up to two hours and come back to perfectly cooked food. And to me, the most amazing part is you can put frozen meat on there, and it's no problem. Cinder can still cook it to your desired doneness with no issues.

"It does have that same aim of cooking food to an exact temperature and holding it there," Ogunbiyi explained. "You can really set it, forget it and know you're going to taste something incredible."

The acquisition made a lot of sense. Maalouly and Ogunbiyi laid the groundwork for Desora by using research and analysis to perfect the barbecue process. Cinder did something similar, but for indoor cooking you could do every night in your kitchen. "We are now working on upgrading [the] software experience and building out an in-depth recipe library specifically crafted for Cinder," Maalouly said.

Throughout 2019, Desora has been working on making its tech more accessible for more people. A key part of that is getting iKamand to share data with Cinder grills, so the outdoors and the indoors are in sync. And all of it will employ the same ecosystem Desora built alongside Kamado Joe.

"As we move forward, we have plans to revolutionize grilling for an even larger part of the population," Maalouly said. Details are scarce for now, but at the end of 2019, Desora plans to reveal the device that it hopes will do just that -- a new product co-created with Kamado Joe.

The company is also exploring ways to integrate its technology, including Cinder's unique algorithms, into other cooking devices and small appliances. Desora isn't committing to what those might be just yet, but you can expect to see new products for indoor use soon.

"It really allows us to expand our product line and think about the future of food and cooking in the home," Ogunbiyi noted.

Desora is also refining existing products. The company is working on a waterproof battery pack for the iKamand, so you don't have to plug it into an outlet to use it with a Kamado Joe grill. This opens up a world of new places you can take your culinary exploits, including tailgates, campsites and more.

The new product that's in development with Kamado Joe is apparently similar to a grill many people use that "just gets the job done." The grill company and Desora want to go a step further, though, so they're building something that feels familiar but gives "insanely great results." Results that may typically require more expensive equipment.

It's easy to speculate on what the two might have in mind. Cheap kettle-style grills that cost well under $100 dominate the industry. But while it's unlikely Desora will abandon the shape and technology it has perfected over the years, a model that's closer in size and price to something like a Weber Kettle isn't too far-fetched. Even something in the $350 to $500 range would attract a lot of attention, especially if it offers similar results to the pricier Kamado Joe options that are currently available.

"What had started off as a class project and a passion for three Harvard-trained engineers has now become a mission that is more important to us than ever," Maalouly said. "The entire BBQ industry is now in the throes of integrating technology into their product line-up, which is a long way from where the industry was when we first started," he continued. "We intend on staying at the forefront."