When body cams had bullets

Don't say cheese...

Just as GoPros have given us a whole new perspective on everything from extreme sports to animal behavior, so have body-worn cameras offered new insights into policing. Law enforcement agencies around the world now use body cams to record the activities of officers in the field, though they've only become commonplace in the last few years. But the idea of documenting the volatile situations officers can find themselves in -- providing both evidence against offenders and holding police accountable for their actions -- is much, much older. The first attempts were very different from the body cams of today, however, as releasing the shutter required pulling the trigger of the gun the camera was attached to.

The relationship between camera and gun goes all the way back to before World War I. So as not to waste ammo and put pilots in unnecessary danger, guns were modified to shoot pictures instead of bullets when the trigger was squeezed. In this way, gunners could be trained with equipment that looked and felt familiar, while their accuracy could be assessed through the resulting photos. This practice persisted through World War II, at which point it also became common to add cameras to live aircraft guns. The footage was a record of how many planes the gunner had downed, the damage done to infrastructure... that sort of thing. If you've ever watched a World War II documentary, you've probably seen clips of this grainy footage yourself.

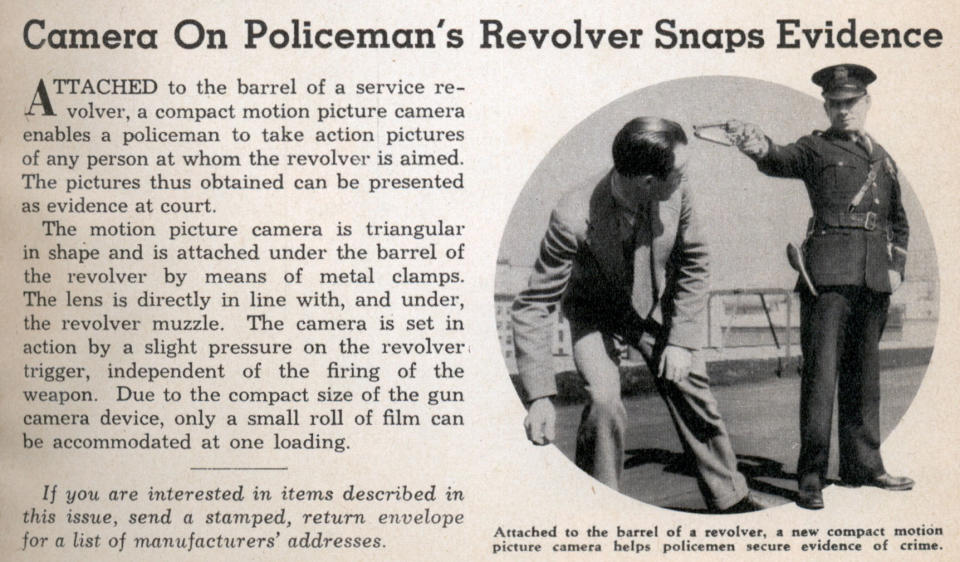

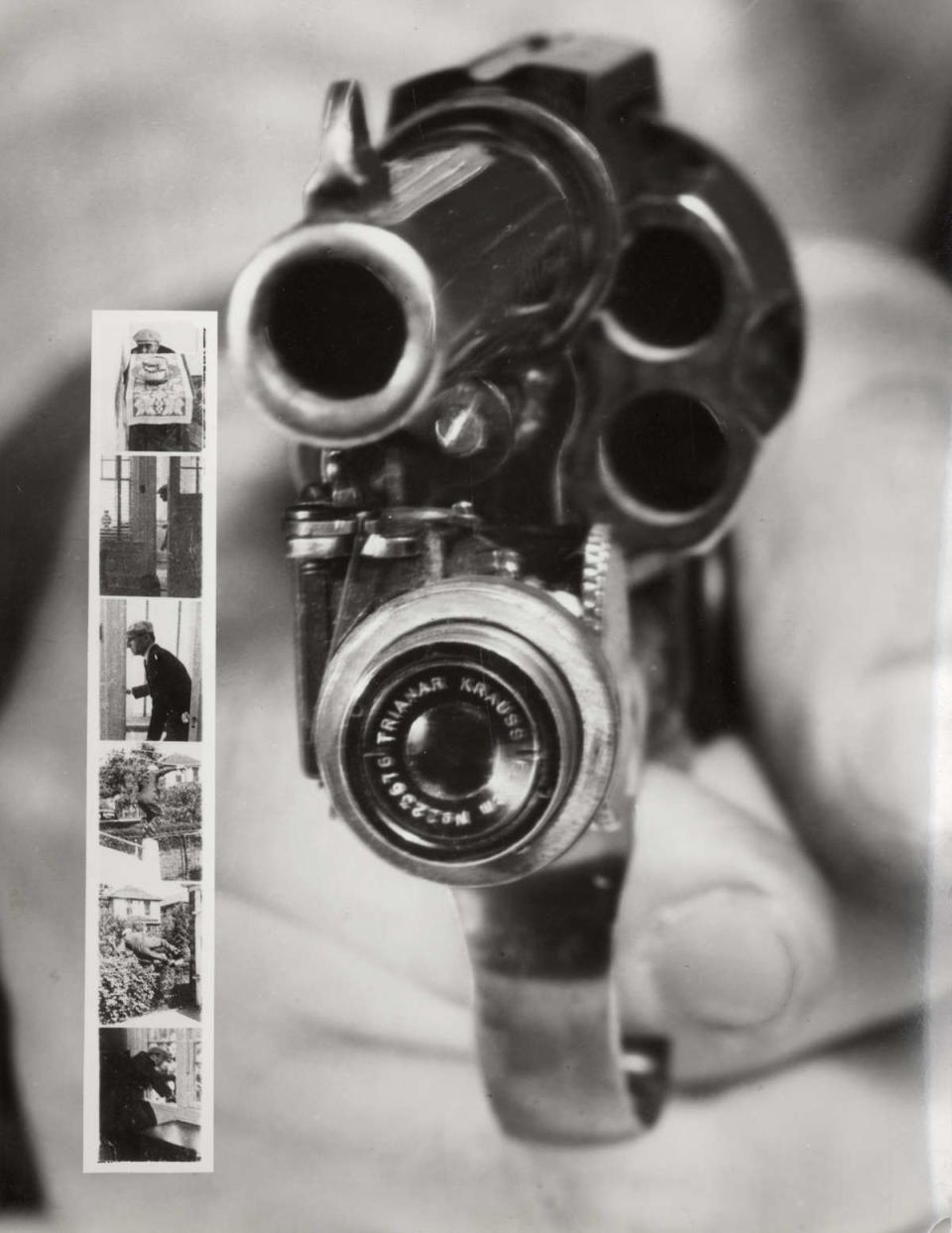

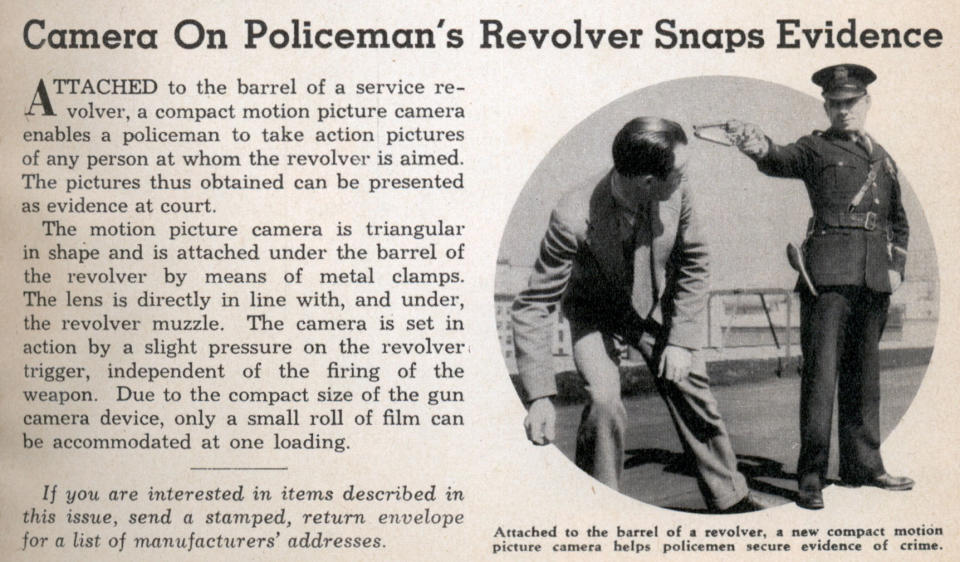

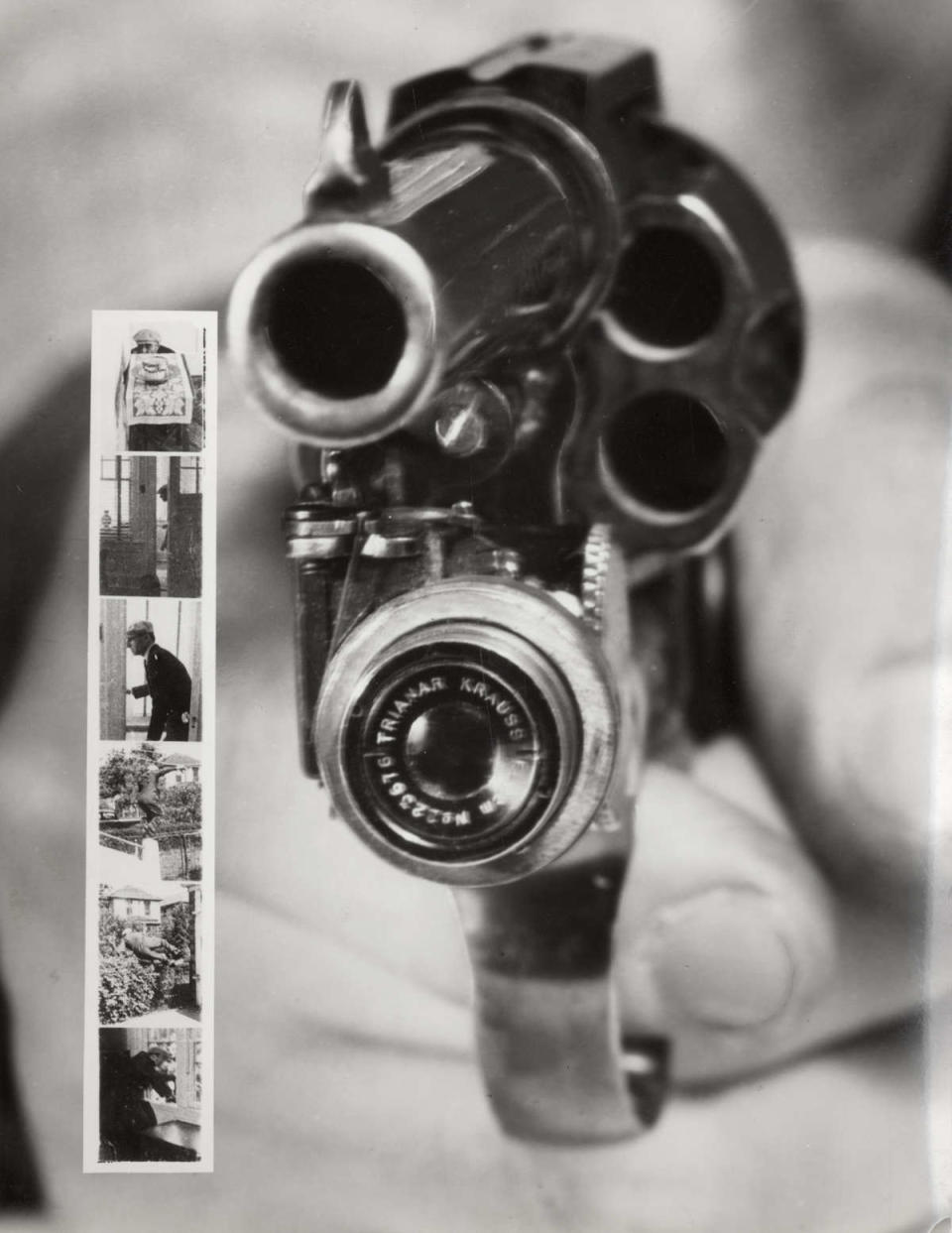

In the mid-1930s, someone transplanted this concept to the handgun. The earliest record of such a marriage is from a Universal Newsreel filmed in Los Angeles in 1935. The footage features the demonstration of a small camera mounted beneath the barrel of a revolver, which recorded video of the gun's line of sight from the moment the trigger was first squeezed until its release. Crucially, this version didn't require the operator to depress the trigger to the point of firing a bullet in order to get the film reel rolling. Other than an article on it appearing in the February 1938 edition of Modern Mechanix, little else is known about the revolver camera, including who developed it.

Perhaps it inspired Abraham Kurnick of New York City, however, who created a similar attachment in 1938. His version was, on the one hand, much more graceful -- the small still camera could be easily fitted to any Colt 38 service revolver, adding 170 grams (6 ounces) to the weight of the gun. On the other hand, taking a picture and firing a bullet were inextricably linked. The miniature roll of film the camera was loaded with was good for six exposures; one for each bullet. As an article in the August 1938 edition of Popular Science explains, "the camera enables an officer to photograph a criminal in case a shot misses."

There's no evidence to suggest either of these revolver cameras were ever procured by law enforcement agencies or made it into circulation by other means. And the idea of wedding gun and camera has failed to catch on even now, at least in any official capacity. There are many, many products of this kind available to regular consumers, such as digital scopes with recording capabilities. But a cop with a camera attached to his service pistol is a rare sight indeed.

In recent history, several companies have tried to sell pistol-mounted cameras to law enforcement. Their purpose being exactly the same as it was in the 1930s: Evidence and accountability. Just over a decade ago, for example, it was Legend Technologies and the PistolCam. In the last few years, it's been Centinel Solutions and the Shield Camera. Axon (formerly Taser) also has an optional camera attachment for some of its non-lethal taser weapons. Handfuls of these product were and still are used, mainly by small, specialist units, but they're nowhere near as prolific as the body cams now routinely employed by law enforcement agencies across the world.

There are several, common sense reasons as to why you would want to decouple camera and firearm. For one, by the time a gun is drawn, you've missed your chance to capture whatever led to the situation escalating to that point. Also, there are scenarios in which footage would be valuable despite an officer not needing to draw their gun at all. Body cams aren't a perfect solution, of course. Wearers are responsible for turning them on, for a start (though Axon is somewhat addressing that with an automated system), and there are cases where footage has been faked or otherwise tampered with after the fact.

There are also legitimate worries body cams could be used in the future for continuous surveillance, as if we needed any more of that in our lives already. But at least they're a better option than the 1930s cameras that took the idea of shooting on film perhaps a little too literally.

Technological innovation didn't begin with the development of the first integrated circuit in the 1950s. Backlog is a series exploring the era of possibilities: engineering feats that followed the industrial revolution, quirky concepts the future's rendered obsolete, and inventions that paved the way for some of the technology we use today.