Video games are more important than ever

IndieCade 2016 highlighted the power of video games to humanize critical social issues.

When Bob Dylan won the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature, it shocked the humanitarian world. What's more, Dylan himself hasn't behaved like a traditional Nobel winner: He hasn't commented on the honor and has yet to give an acceptance speech. At least one member of the Nobel panel has called Dylan's silence "rude and arrogant," and the public has been reminded that if he doesn't give a lecture within six months, he won't receive the $900,000 prize money. It's a new kind of strange in-fighting scandal for the Nobel community.

However, it's not surprising. Selecting Dylan as a Nobel laureate may be contentious, but it's mostly a sign of growth for intellectual society -- at least in Literature, no one is off-limits, not even mumbling masters of wordplay and songwriting. Growing pains are expected as the world of mainstream politics, activism and academia is suddenly forced to consider the potential of new industries and vice versa.

Songwriting might just be the beginning. With the growing accessibility of high-end living-room consoles and virtual reality headsets, it's easy to imagine a video game on a list of Nobel nominees in the near future. Nowhere was that more apparent than at IndieCade 2016, an annual festival celebrating independent video games held in Los Angeles, California.

"Bob Dylan is an iconic cultural hero because he's transcended his language -- he's actually in a more unique situation than, let's say, a video game, because the video game has the ability to immediately be on your computer, be pretty quickly localized and then become your personal experience," said Navid Khonsari, creator of 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, a powerful narrative-driven adventure game that puts players in the shoes of a photojournalist during the Iranian Revolution. "So I think that there's great, great potential and possibility [for a game to win a Nobel]."

In the middle of a bustling demo room at IndieCade, Khonsari discussed how 1979 Revolution was his story, even though he was a child during the actual political upheaval. Khonsari lived in Iran until he was 11, and in between motion-capture sessions and coding marathons, he sprinkled the game with grainy home movies of his family in the country. As much as 1979 Revolution is an attempt to humanize an uprising that forever changed Iranian society, its story remains near to Khonsari's heart, almost as if he's still trying to explain the revolution to his 10-year-old self.

It's a personally relevant tale with an eye on broader social impact, much like celebrated books 100 Years of Solitude or The Grapes of Wrath (both Gabriel García Márquez and John Steinbeck were awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature).

Khonsari spent years working for big-budget AAA studios, including six years at Rockstar Games where he crafted experiences including Grand Theft Auto III, San Andreas and Vice City, Red Dead Revolver and the Max Payne games. After finishing work on one of the Grand Theft Auto titles, Khonsari returned to Iran and spoke with people living there about their perspective of life in the United States. Their responses shocked him.

One woman based her views of life in the US on one of his titles, Vice City -- a game where players can drive around, go shopping and listen to the music they choose, whenever they want. There's an inherent freedom in the game's sandbox design. It excited and enraptured this woman.

This conversation was a turning point for Khonsari and his view of video games' role in social change.

"I was like, shit," he said. "This has some serious impact. Far greater than films, far greater than books. This is the most powerful tool that we actually have out there and we're not engaging with it in the [best] way that we could."

One way that Khonsari believes video games can infiltrate mainstream social change is via virtual reality. VR can create a more immediate, intimate and powerful experience, he said.

"With a combination of virtual reality, which I think is really interesting, augmented reality -- the ability to have influences in a collection of work that manifests itself to actually provide change is very, very strong, and more importantly, can have an appeal and an impact on an international audience," Khonsari said.

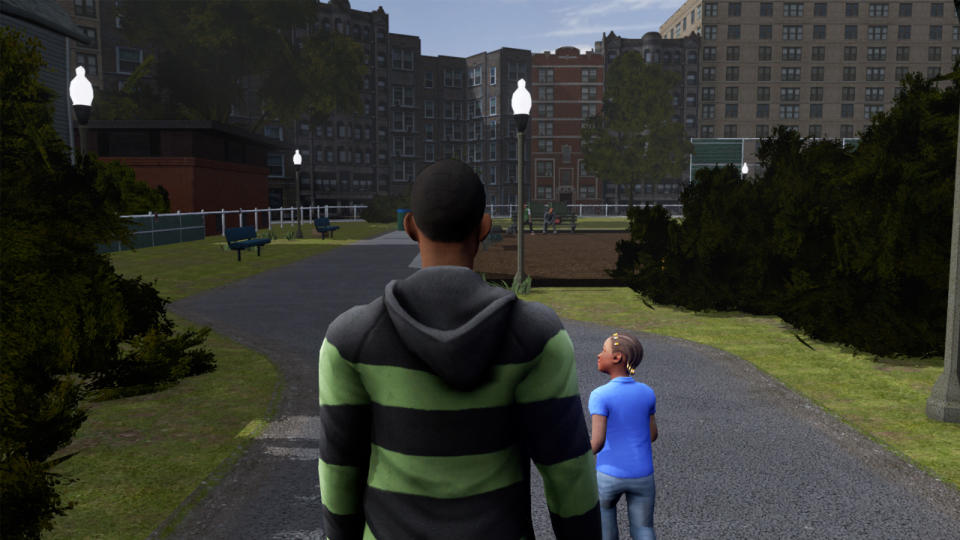

We Are Chicago, Culture Shock Games

He's not alone in this belief that VR and AR can change the public perception through video games. Cynthia Miller is the designer of We Are Chicago, a narrative-driven adventure game about real life on the south side of Chicago -- gang violence, economic insecurity and all.

"Because of the way our brains are wired, being put in the virtual reality environment I think has a lot of impact on people," Miller said. "I think that's helping our case with social games, empathy games. And as more games come out talking about immigration or issues with abusive relationships and stuff like that -- I've heard people talking about working on these games -- and as these games come out, I think more people will understand it as an art form that can be entertaining, but also can change the world."

We Are Chicago was part of the Gaming for Everyone exhibit at IndieCade 2016, where it was surrounded by other titles and organizations focused on influencing social change or supporting equality in the gaming industry.

Another title in the Gaming for Everyone exhibit was Blue Cat, a student project that puts players in the paws of a house cat named Blue who lives with Rose, an older woman suffering through a dark time of depression. It's based on Pablo Picasso's Blue Period, which was followed by his more influential and famous Rose Period, creator Simone Castagna said.

"Those two people seem so different; it's completely different art styles, but they're part of the same person," she explained.

Blue Cat, Simone Castagna

Blue Cat isn't only influenced by Picasso and classic art. It's a personal story for Castagna -- a way of working through real, tragic things that happened in her life. Just as We Are Chicago is based on interviews with people in the city and 1979 Revolution puts a human face on a massive upheaval, Blue Cat tells a deep, honest and vulnerable story about the limits of human strength.

"My mother was suffering from schizophrenia, and she seemed to regret a lot of her life," Castagna said. "We had a very difficult time; we were very, very poor. And when the schizophrenia hit – the main character in this, she behaved very similarly. Repetitive actions. I guess she already thought of herself as dead. And unfortunately, she did end up committing suicide."

Blue Cat is personal to Castagna but it offers a clear message for anyone who picks up the controller. The game manufactures empathy for someone who is giving up on life, live on the screen -- for some players, it's the first time they encounter mental illness in such a direct way. It can be an eye-opening experience.

It's also soothing for Castagna herself. She and a small team made Blue Cat while they were finishing up school, but she's now just left a job at Disney as a technical game designer and she's considering whether to take a chance on developing Blue Cat full-time. She doesn't want to re-enter corporate life, but there are drastic challenges in securing funding for full-time independent development.

"This game was me dealing with how I wish she could have forgiven herself, but also how I need to forgive myself for what I couldn't change about her," Castagna said. "Basically, the greatest gift that I could give myself and her legacy, is by trying to keep pushing forward and really living the best way that I can as a human, what I consider a human to be. And I think she would be proud of that."

Blue Cat, Simone Castagna

IndieCade was packed with games tackling social issues or attempting to establish empathy with players, even outside of the Gaming for Everyone exhibit. Joining 1979 Revolution as a nominee in the IndieCade Festival Awards was Killbox, a simple yet poignant game about the dehumanizing aspects of drone warfare.

"People are starting to realize that you can use games for more than entertainment," Killbox programmer Albert Elwin said.

Elwin didn't think much about UAV warfare before starting work on Killbox, but its development and the research involved revealed to him "the horrific things that have gone on and are going on today," he said. After this experience, he believes that video games will absolutely reach a point of serious consideration in mainstream conversations -- and even win a Nobel prize -- some time soon.

"They'll definitely reach that point," Elwin said. "I'm not entirely sure when -- it's going to be, I'd say, at least 10 years, but it could be a lot more than that. It takes a long time for people to kind of -- you need to get through all the generations of people, to get to the point where people have actually grown up with games and know what they are and be critical about them."

In terms of approach, not much separates the creators of video games like 1979 Revolution, Blue Cat, Killbox or We Are Chicago and the author of a celebrated novel, book of poetry or portfolio of songs. The tools are different, but the message is clear.

Killbox, Biome Collective

"I'm not saying games can provide world peace because there's a lot of other parts that need to move, but they can actually start a conversation that goes beyond the single dimension of how countries, regions, people, politics and conflicts are being portrayed in single, five-minute news pieces that generalize an entire nation or group of people," Khonsari said.

In fact, 1979 Revolution is already getting attention from at least one major traditional humanitarian organization: the United Nations. On top of being adopted in schools in the United States, Australia, Canada and Norway, 1979 Revolution will feature in a UN-commissioned paper as a case study on conflict resolution in digital experiences, written by teacher Paul Darvasi. Darvasi will present the paper to UNESCO, the UN's educational, scientific and cultural organization, in the near future.

For Castagna, the creator of Blue Cat, nothing separates video games from any other art form. They're created with the wider world -- or even deeply personal experiences -- in mind.

"I think that art is vulnerability," she said. "In my opinion, one of the things that's keeping us from growing faster is that we aren't vulnerable with each other. I think somebody has to take that risk."