The Colorado startup dreaming up a return to supersonic flight

Boom Supersonic hopes to test-fly its supersonic plane in 2021.

In less than 50 days, a company will unveil what it hopes will be the plane to kickstart a new generation of supersonic flight. On October 7th, Boom Supersonic is planning to show off the XB-1, its single-seat test craft, with flights planned for next year. It’s early days, but what happens in Colorado in the next 18 months could have lasting consequences on how we fly.

We’ve been here before. In the 1960s, the British and French governments came together to build a supersonic liner. Concorde began flying in 1969 and entered commercial service in 1976, with its last flight taking place in 2003. There’s only been one other civilian supersonic transport (SST), the Russian-made Tupolev TU-144, but it barely counts. Most students of aviation history know that the plane made less than a hundred passenger flights before retirement.

Concorde’s life played out the latter half of the 20th century in microcosm. Created in an optimistic era by engineers who solved the plane’s challenges in longhand. This mechanical marvel, fast and reliable, flew at Mach 2.04 and, along with the moon landing, marked the high point of humanity’s technological achievement. By the time that it came into service, much of that optimism had given way to cynicism.

In the righter-wing decades that followed its birth, we simply decided to walk back from the future. Concorde wasn’t abandoned because we improved upon it, but because it was cheaper to do something worse. Why let a handful of people cross the Atlantic in a couple of hours when the jumbo jets (that were developed concurrently) can do the same at far lower cost?

Two decades later, and a new generation of entrepreneurs, tired of waiting for another optimistic age, are trying to build it themselves. That’s where the Colorado-based Boom Supersonic and its founder, Blake Scholl, come in. Scholl describes himself as an Objectivist (a follower of the teachings of Ayn Rand) and previously worked for both Groupon and Amazon. He freely admits that, beyond his private pilots license, he does not have an aerospace background.

During our talk, Scholl referenced SpaceX a number of times, and it’s clear that Elon Musk’s private spaceflight company is the model Boom is striving to emulate. “You know, when SpaceX got started, it was a joke that a startup could build a rocket,” he said “and not that many years later, they’re landing rockets vertically on pads.” Scholl’s ambition is to do for supersonic travel what SpaceX did, and is doing, for the space industry.

1/ In the pre-founding days of @boomaero I worried “what do *I*—an Internet prod/eng guy—bring to the table?”

— Blake Scholl (@bscholl) July 31, 2020

One of the things that Scholl and Boom are banking on is the advances in computer-aided design and materials science. The single-seat, 71-foot long XB-1 is designed to test if these advances will make building a supersonic plane far more efficient and cheap than it was in the ‘60s. XB-1 will use a variety of molded carbon fiber composites for its body that should hold up better against the heat and stresses caused by supersonic flight. The company says that the plane should be able to withstand temperatures exceeding 300 Fahrenheit (148C).

Concorde had no on-board computer and had a movable nose; Such was the angle of attack upon landing that Concorde’s nose had to drop in order for the pilots to see where the ground was. The XB-1 ditches that in favor of cameras on the nose and landing gear, hopefully reducing complexity. And the plane’s design has been refined (in a virtual simulator) to ensure a high fineness ratio, a fancy way of saying the plane is shaped narrow and pointy to reduce drag at high speeds.

XB-1 will be piloted by Commander Bill ‘Doc’ Shoemaker, a 21-year US naval aviator who led combat missions in an F-18 on a number of occasions. He has also served as a flight test instructor at the US Navy test pilot school and previously worked for Zee.Aero, one of (Google co-founder) Larry Page’s self-funded flying car startups.

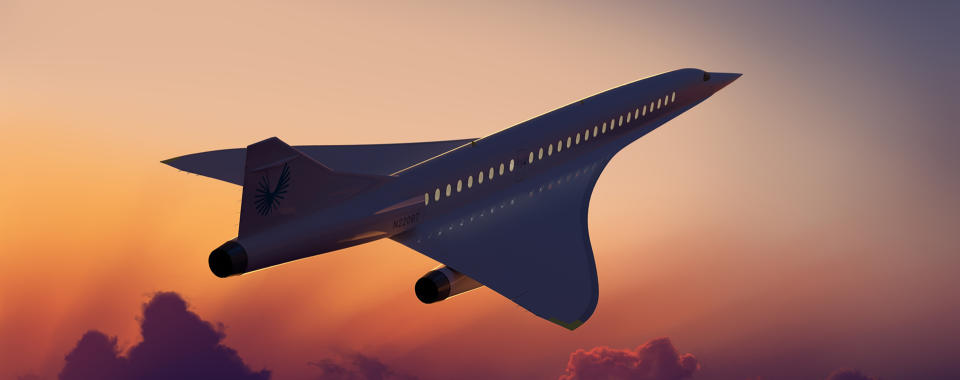

If XB-1 proves successful, then Boom will move to begin building its full-size supersonic plane, Overture. Overture is a craft designed to seat less than a hundred people at “business class” levels of comfort. And for “business class” prices, they’ll be able to fly from, say, Tokyo to Seattle in four hours and thirty minutes.

One problem with there being a singular example of the technology in history is that all discussions inevitably lead back to Concorde. One of that plane’s biggest failures was emissions: it was notorious for guzzling gas and emitting highly toxic particles. Boom has already pledged that its test program will be entirely “carbon neutral” and that its planes will set the bar for energy efficient planes.

“One of the principal reasons that Concorde wasn’t affordable was that it just consumed too much fuel,” said Scholl. “Fast forward 50 years and none of those things need to be true any more.” XB-1 and Overture are designed to use alternative fuels, rather than the kerosene mixes found on some liners today. Scholl said that as well, the company is working with other businesses to develop airline grade fuel through direct air capture.

Direct Air Capture is a system that draws carbon dioxide out of the air and recombines it to create hydrocarbons. Companies like Carbon Engineering are working on systems to mass-produce fuel in this way to create (if you squint) “carbon neutral fuel.” Of course, that still requires the burning (and releasing) of carbon back into the atmosphere but the hope is that, if more CO2 is extracted than used, it’ll be more virtuous than existing fossil fuels.

Boom also promises its planes will use less fuel through a combination of efficient materials and better engines. Scholl said that the planes are powered with a “quiet, efficient turbofan system [...] a similar engine architecture to what you’d see on any large Airbus or Boeing wide-body aircraft today, just adapted for supersonic flight.” And recently, Boom announced that it was teaming up with Rolls Royce to build an engine for Overture.

Concorde was killed by economics -- it was too expensive to run and far too expensive to support, especially as it got older. British Airways had to buy its contingent from the UK government at famously knock-down rates to keep them going. Scholl says that Overture is going to be expensive, but that Boom’s lack of a legacy is as much of a benefit as it is a burden. “We don’t have to think about the 737 Max, we don’t have to think about how to keep the factories running for our last-generation airplanes,” he said, claiming that Boom has the “luxury of focus.”

Scholl expects Overture to cost just $6 billion to develop -- by comparison, a 2011 Seattle Times report claimed that Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner cost $32 billion to design. But Scholl is planning to sell 2,000 Overture aircraft for “$200 million a pop,” which he says is a “$200 [billion] to $400 billion market opportunity.” Those targets represent an ambitious plan to effectively swallow the majority of global business travel. If successful, such a move would render traditional long-haul business class obsolete.

Except, of course, that launching a supersonic plane to bring the world together and enable a new generation of business travel isn’t ideal in 2020. We are, of course, struggling to deal with a pandemic that has dramatically discouraged air travel for anything but essential reasons. As I wrote back in June, COVID-19 will see a dramatic reduction in people flying, enough to kill off some of the airline industry’s biggest planes. (That said, the economics of flight mean that a smaller plane with fewer passengers, flying at capacity each time, will likely remain profitable. Which suggests that Overture’s sub-100 capacity and high speed may be the ideal vehicle for post-pandemic travel).

“We’re still a few years away from flying Overture and carrying our first passengers,” said Scholl, “and by the time that happens, COVID will be a distant nightmare.” Scholl says that Boom is “designing Overture to be the first post-pandemic airplane.” Both because you’ll be spending less time in the air, and also down to cabin airflow modeling Boom is planning to do. Scholl says he expects Overture’s cabin to be “safer than a typical restaurant.”

And Scholl isn’t too worried about a depression in business travel, saying that video conferencing cannot replace the “human connection.” He cited statistics claiming that private air travel, while still below 2019 levels, is still up on commercial flights. Scholl expects that, in the next decade or so, when the global health crises and economic crises are behind us, flying will be back in demand just at the time that Overture is ready to satisfy it.

It’s still early days, of course, and right now the first step on the road to a second supersonic age sits half-finished in a Denver warehouse. But that’s how all of these journeys begin, with unbridled (and sometimes unfounded) optimism. As the commercial aviation industry enters one of its darkest periods in a generation, perhaps a dose of optimism is exactly what’s needed.