Women, LGBT least safe on Facebook, despite 'real name' policy

Despite Facebook's insistence that its "real names" policy keeps its users safe, a new report reveals that Facebook is the least safe place for women online. And things are turning more explosive, as stories emerge that Facebook has been changing its users' names without their consent -- and the company isn't allowing them to remove their real names from their accounts. Meanwhile, a furious LGBT coalition has rallied around the safety threats posed to its communities by the policy. Though, it was unsuccessful in blocking the company from marching in America's largest gay pride parade.

Facebook's ongoing war on pseudonyms became well-documented in 2011 when a blogger risking her life to report on crime in Honduras was suspended by the company, under its rule requiring everyone to use their real name on the social network. The problem re-emerged in September 2014 when Facebook's policy locked an eye-opening number of LGBT accounts in violation of the "real names" rule. Facebook met with Bay Area LGBT community representatives, offered an apology, then suggested a policy change was in the works. Surprise: It never came. Nine months later, Facebook has failed to solidify or clarify this policy, and one organization has bad news for Facebook's years of "real name" policy implementation.

Epicenter of online abuse for over 23 million women

The Safety Net Project (at the National Network to End Domestic Violence, NNEDV) recently released a report based on results from victim service providers called A Glimpse From the Field: How Abusers Are Misusing Technology.

The report found that nearly all (99 percent) the responding programs reported that Facebook is the most misused social media platform by abusers. Facebook is a key place for offenders to access information about victims or harass them by direct messaging or via their friends and family. The respondents included national domestic violence programs, sexual assault programs, law enforcement, prosecutor's offices and civil legal services.

Facebook is the most misused social media platform by abusers.

NNEDV's report (PDF) concluded that, "It is unsurprising that nearly every program reported Facebook as the main social media abusers use to harass victims." That's because, "Facebook is the hardest for survivors to shut down or avoid because they use it to keep in contact with other friends and family." And no wonder, because NNEDV recognizes the critical need to avoid isolation for abuse victims. "Although we often hear suggestions that survivors shouldn't use social media, we don't agree that this is a solution."

NNEDV tells us that one in four American women are domestic abuse survivors; in one recent 24-hour survey, NNEDV found that US domestic violence programs served more than 65,000 victims and answered more than 23,000 crisis hotline calls in one day alone. It's widely accepted that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender survivors of violence experience the same rates of violence as straight individuals.

Pew currently estimates that 71 percent of American adults (188 million) use Facebook; if half are female, and one in four of those are victims of domestic violence -- that's a little over 23 million women whose "real names" put them in danger. And that's 23 million users who, especially if they are using the social network by its own rules, are experiencing Facebook as their primary avenue of abuse, harassment and stalking.

When reached for comment about the How Abusers Are Misusing Technology report, a Facebook spokesperson referred us to this Facebook post explaining how the company's "authentic name" policy "creates a safer community for everyone."

The Facebook prison experiment

On its website resource for survivor support, NNEDV adds, "Getting off social media doesn't guarantee any level of safety or privacy. Additionally, online spaces can decrease isolation and offer much support for survivors, especially when they offer privacy and security controls to the user. Survivors shouldn't have to worry about their safety when they want to connect with friends and family online."

Facebook's very public 2013 partnership announcement with NNEDV shows that the company is fond of saying one thing, and instead doing the opposite.

Obviously, the status of that relationship is "complicated."

NNEDV's own Survivor Privacy Guide instructs survivors of abuse to never use their real names on social media accounts. "Survivors can maximize their privacy by using being careful about what they share, strategic in creating accounts (not using your real name in your email or username) and using privacy settings in social networks."

The Survivor Privacy Guide isn't just the policy on "real names" for domestic violence victims; is the bedrock instruction and most-cited policy for digital safety by every national sexual assault organization in the United States (including the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence, National Sexual Violence Resource Center and numerous state coalitions against rape and Violence Against Women).

In NNEDV's Facebook guide for abuse survivors, it acknowledges both that Facebook's policy is to only use your "real name" and that an account's user name is one of the only things that can never be made private. The official NNEDV guide tells abuse victims and assault survivors the only option to avoid being abused, stalked and harassed by perpetrators by your real name on Facebook is... to not use Facebook.

"Victims of domestic violence, sexual violence and stalking have even more complex safety risks and concerns when their personal information ends up on the internet," says NNEDV's Being Web Wise guide -- where NNEDV advises only posting online anywhere using a "pen name."

In the nine months since drag queens made headlines about Facebook's "real names" problem, the situation for LGBT people, sex workers, and female users has continued, and worsened.

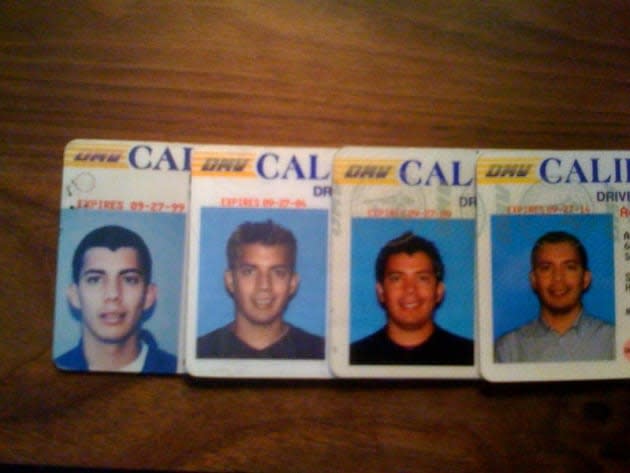

Facebook, in the meantime, has kept its assurance in "expanding the options available for verifying," which now includes portals where users are told to upload their driver's licenses and passports (among many other official documents) to unlock their suddenly locked accounts. By May, the steady stream of reports that LGBT people were still being locked out of their accounts and forced to provide their legal name documentation (a terrifying predicament for many LGBT people) hadn't abated.

Believing Facebook is more interested in appearances than the LGBT community's worsening user safety problem, Bay Area LGBT figureheads concretized a movement, the MyNameIs Coalition, with a campaign to ban Facebook from this Sunday's SF Pride parade -- placing Facebook in the same category as other corporations who discriminate or behave harmfully toward LGBT people as a group, such as Coors and Exxon Mobil.

Local headlines read that the Pride board bent to pressure from Facebook.

The decision prompted the SF Examiner to write, "If you're a high-profile donor to San Francisco Pride, you might be able to discriminate against the LGBT community and get away with it." In at least one instance, Mark Zuckerberg placed at least one personal call to a board member.

According to meeting minutes, Pride board member Jesse Oliver Sanford railed at those who voted for Facebook saying, "What does it say if all it takes is a 15-minute phone call from Zuckerberg for Pride to sell out our own community?"

When reached for comment, SF Pride President Gary Virginia explained to Engadget that SF Pride would be focusing on finding a "solution to expand [Facebook's] authentication policies and procedures" in community meetings sometime in the "next 12 months."

"What does it say if all it takes is a 15-minute phone call from Zuckerberg for Pride to sell out our own community?"

Regarding the decision to keep Facebook in the parade, Virginia said, "We look at the totality of intentional support or harm to our queer community when vetting a potential sponsor or parade contingent. FB has been a staunch supporter of our queer community and has a perfect 100 score on the Human Rights Campaign Corporate Equality Index. These are the main factors that drove the board's decision to continue to welcome Facebook's LGBT employee group in the parade and Facebook's sponsorship."

When reached for comment about SF Pride's decision in light of MyNameIs Campaign opposition, a Facebook spokesperson told Engadget, "Facebook is proud of our commitment to diversity and our support of the LGBTQ community as a company and an employer. We have been strong supporters of the San Francisco parade for many years. ... We look forward to joining this year's 45th annual celebration."

However, Facebook didn't have anything to say to us about reports that the company is changing its users' names without their consent.

At the same time MyNameIs began organizing its movement, some Facebook users discovered that Facebook is changing the names on their accounts to what Facebook believes is their "real name" -- and they have no choice about it.

Stupid facebook, logged me out & changed my name on me. now I can't change it back for 60days. YES, Sherry Ann Ey is me 'Rooster' :)

— Sherry Ey (@sherryey) May 27, 2015

User Sherry Ey wrote on May 26th, "Stupid Facebook, logged me out & changed my name on me." MziAMARt tweeted on June 10th, "They kept me from my account for the last two days then CHANGED MY NAME." On June 12th, Marilyn Ollie wrote, "So freakin upset with Facebook. How you gone send me an email and tell me that you changed my name and I can't change it back." User Modar Almouhammad wrote on June 16th, "Facebook changed my name without even asking me?"

One woman, who spoke under condition of anonymity, told Engadget that six weeks ago, Facebook flagged her name as "inauthentic" and was told to change her name. She did -- to the name on her ID. She said, "Two weeks later I received another notification that they didn't think that the name I had entered was my 'authentic' name and that I had to submit documents confirming that."

She uploaded her ID and submitted her user name to be her first and middle name, as seen on her ID. She told Engadget, "I found that when I had my profile set to my name [first and last] that I had unwanted attention from people at my day job tracking me down and able to view my profile pictures, generally available photos, view my website and essentially able to stalk me in a way that made me feel unsafe."

But Facebook had its own plans after the company obtained her ID. "I received notification within two days of uploading my driver's license that they didn't accept my [first and middle name] as my legal name and would change my name to my [first and last name] unless I could provide other identity."

She said Facebook told her, "I would not be able to change my name again. Not in three months -- never."

This flies in the face of Facebook's own publicly stated policy following the September drag queen dust-up, when CPO Chris Cox released a statement saying:

"Our policy has never been to require everyone on Facebook to use their legal name. The spirit of our policy is that everyone on Facebook uses the authentic name they use in real life. For Sister Roma, that's Sister Roma. For Lil Miss Hot Mess, that's Lil Miss Hot Mess."

The biggest unregulated private database on earth?

Facebook appears to have started forcing birth names on its users around the time of the September 2014 LGBT name purge, as seen in this nine-month-old plea for help on Facebook's Help Community page. Triex Keiseki wrote, "I provided Facebook with my original birth certificate and my name change certificate -- instead they changed my name to my birth name, which I have hidden for the past years. ... and I SPECIFICALLY DID NOT WANT people to know."

Engadget spoke with two other women, and one gay male performer who has received actionable threats, each of which are terrified to experience Facebook changing their names without consent, or recourse.

Facebook maintains that its "real names" (aka "authentic names") policy is essential for user safety. It believes its "authentic names" policy protects users from abuse on the social network, "like when an abusive ex-boyfriend impersonates a friend to harass his ex-girlfriend" because "no one can hide behind an anonymous name to bully, taunt or say insensitive or inappropriate things." But rumblings about Facebook's real motivations -- to prioritize the financial value of its database are the inevitable chorus it receives in the media; Facebook's stock tanked in 2012 when it revealed 8.7 percent of its accounts to be fake.

Facebook maintains that its "real names" (aka "authentic names") policy is essential for user safety.

As Reed Albergotti wrote in The Wall Street Journal last year, "Facebook's advertising product, which will bring in an estimated $12 billion in revenue this year, rests almost solely on its ability to gather detailed, accurate information about users."

Either way, it's a hell of a database score, though it stands to reason there are humans in there somewhere: That Facebook is changing user names based on the submitted documents shows that Facebook is indeed recording submitted ID information with the user account record, somewhere.

It's interesting to note that databases such as this are usually subject to citizen protections; for instance, the Drivers Privacy Protection Act (DPPA) restricts what state motor vehicle departments can do with our driver's license data -- as well as who can handle that data.

Collecting passports, marriage certificates, state ID, birth certificates, library cards, Social Security cards, insurance cards and more as part of Facebook's identity verification data set must make for an unimaginably impressive candy store for governments, advertisers, stalkers, unethical corporations, and all the creeps in the internet's clown car.

As someone who writes about privacy and security for a living, I'd say it's easily one of the most dangerous, highly targeted, unregulated private databases on the planet.

But no matter its monetary value, the view from here looks as if the cost is too high.

[Image credits: Getty (Protest, Pride parade), Facebook (Lisbon), AP (Lil Ms. Hot Mess, Sister Roma and Heklina), Flickr (Driver's licenses), Shutterstock (Facebook app)]