'Super Mario Maker' crushed my dreams of making video games

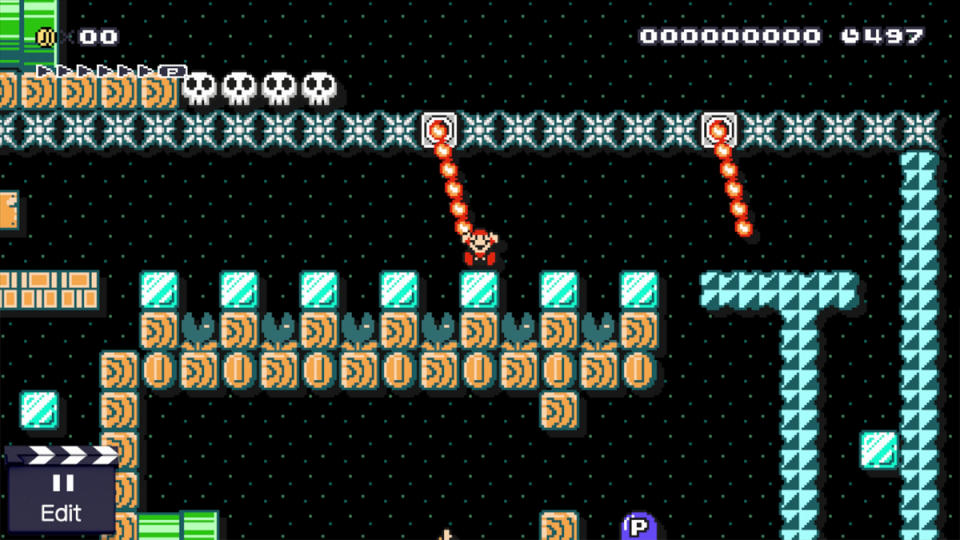

"Isn't this supposed to be fun?" I asked myself over and over again. I knew the answer was "yes," but I still wasn't having any. I'd been playing Super Mario Maker, a video game that lets you make your own Super Mario Bros. levels and play them on a real Nintendo console, and I was completely miserable. It didn't make any sense. I'd dreamed about making Nintendo games since I was 6 years old, but when the company gave me the chance to prove a game design genius lived under my skin, I flopped. It was then that a shocking and heartbreaking realization washed over me: I hate making video games.

My ego didn't take this realization well. As both a hobbyist gamer and a journalist that covers games, I've always humored the little voice in the back of my head that said, "I could do this if I wanted. I could make games." No, Super Mario Maker has shown me, I can't -- not really. Yes, technically I can construct a stage from set pieces I've seen in other Mario games, but I'm not really creating anything. My by-the-numbers Mario levels (a few power-ups to start, some pipes to leap over, maybe a Hammer brother or two and a flagpole at the end) feel more like light plagiarism than original content. Why do I suck at this so much?

Objectively, I knew that my failure to fall in love with Super Mario Maker's level editor is little more than a simple mismatch with my own creative sensibilities, but the reality of it still bothered me to the core. My self-image has always revolved, in some fashion, around the idea that I am a creative person; Super Mario Maker contradicts that in a way that other DIY game builders never have. When Minecraft's building mode failed to garner my attention, I easily dismissed it as just "not my thing." When Disney Infinity's sandbox world didn't spark my interest, I blamed it for having "convoluted" tools that weren't "straightforward." I can't apply these excuses to Super Mario Maker. I love Nintendo's platforming games and Maker's creation toolset is as intuitive as they come. I'm the problem, not Super Mario Maker.

Coming to terms with this was like getting punched in the gut. If I'm not having fun making Mario levels, is that proof that I'm not really the creative-type I see myself as? I couldn't accept that. "I'm a dang writer," I told myself. "I'm not going to let some video game throw my personal identity into question." I scoured the game's online Course World mode for inspiration from highly rated level designers and pored over Nintendo's official Super Mario Maker Idea Book, but still wound up with terrible, boring levels that weren't fun to make or play. In a last-ditch effort, I turned to the internet for help. There, scattered across Reddit, Twitter, Facebook and a dozen gaming forums, I found my answer. This is a skill, not a talent.

My soul settled as I realized my failure wasn't a lack of creativity, but another belief that closely orbits my fragile sense of self: There's no such thing as effortless, natural talent -- only the gumption to learn and master a skill. Online, I found level designers who had spent hours carefully planning out their stages before they ever touched the Wii U GamePad. They drew them on graph paper; they brainstormed ideas with friends and told stories through level design. My childhood dream of creating games was merely romantic, but for these people it had been a practical passion. They drew levels on paper; they used other game-making programs; they built up their love for game design as a skill. I didn't. It's as simple as that.

It took me awhile to figure out, but Super Mario Maker taught me that game design is a lot like writing. On the surface, it sounds easy -- but the truth is that it's a skill that needs to be pursued, learned and developed. There are unspoken rules that have to be followed, and good writing (or design) requires planning and forethought. Nobody sits in front of a blank sheet of paper unprepared and writes the next great American novel (despite our egotistical assumption that we can), Pulitzer Prize-winning essay or, well, award-winning Super Mario Bros. game. It takes practice, experience and passion. I have all of those as a writer, but none of them as a game designer.

I may never be a great game designer, but thanks to Super Mario Maker, a mild reality check and a little more thought than I ever expected to dedicate to a Japanese-Italian plumber, I now have a much better idea of what it takes to be one. I think I've always known, but it's nice to be able to consciously recognize it and give the folks who have put the effort into cultivating their skills the respect they deserve.