'To Live and Die in LA' shows how much Google knows about you

There's a jarring moment in Neil Strauss' true crime podcast.

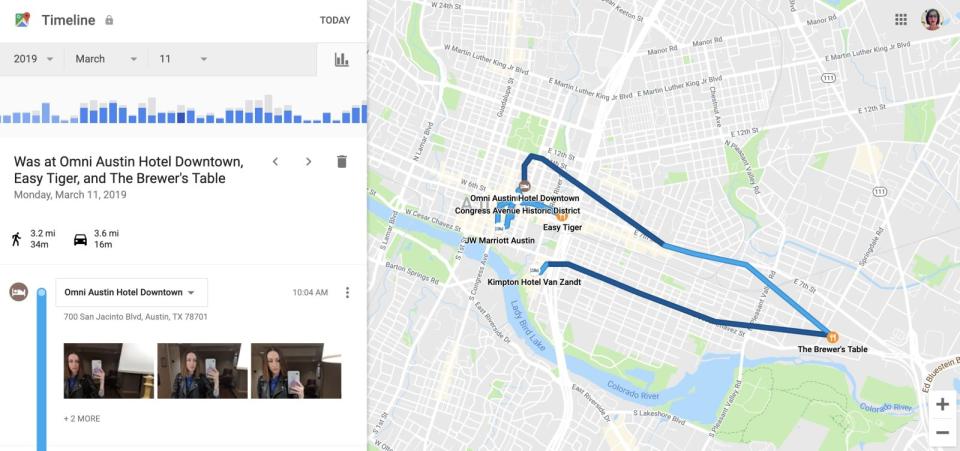

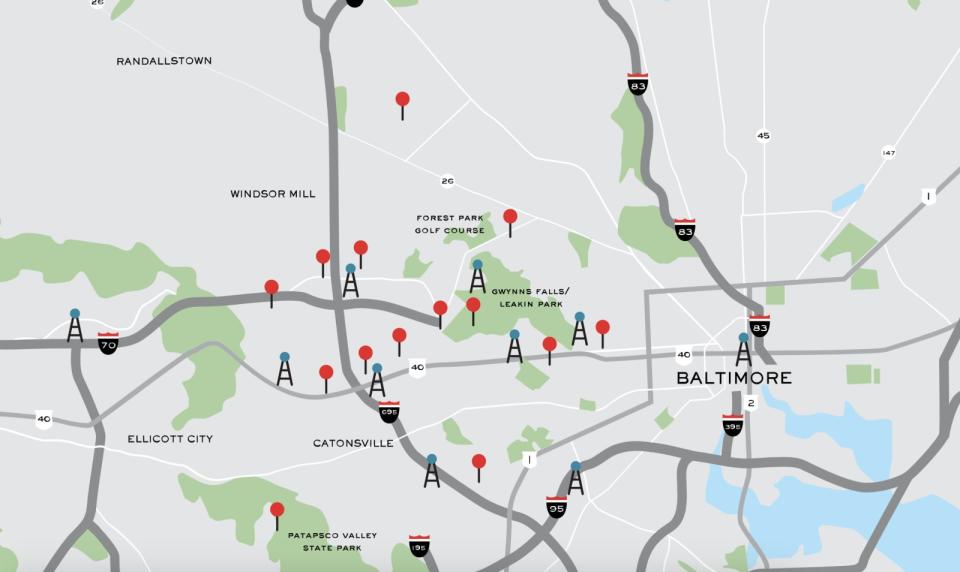

In episode five, season one of the podcast Serial, Sarah Koenig navigates the strip malls and parks of Baltimore, attempting to fulfill a challenge set down by Adnan Syed -- the convicted murderer whose case she's investigating. Over a prison phone, Syed tells Koenig the state's timeline of the murder is impossible, so she gathers reams of call logs and cell tower records, and pieces together the route he supposedly took the night he killed his girlfriend in 1999. Memories from witnesses have changed over the years, but the data points on the cell tower map tell the same story every time.

Still, it takes a lot of guesswork. Koenig drives between Woodlawn High School, Best Buy and Leakin Park, trying to match the stories of professed witnesses to the pings from Syed's phone. The Serial map shows 10 cell towers covering a six-mile stretch of Baltimore, and as Koenig drives around the area, she notes the pings don't match the story told by the state's lead witness.

It's not enough to exonerate Syed. His lawyer apparently mentioned the discrepancy, vaguely, in Syed's initial trial, but she seemed unprepared to discuss the technical details behind cell-tower location tracking. In the end, the ambiguity of a ping, which could stem from a phone miles away from the actual tower, wasn't enough evidence for the jury. They trusted the witness and convicted Syed.

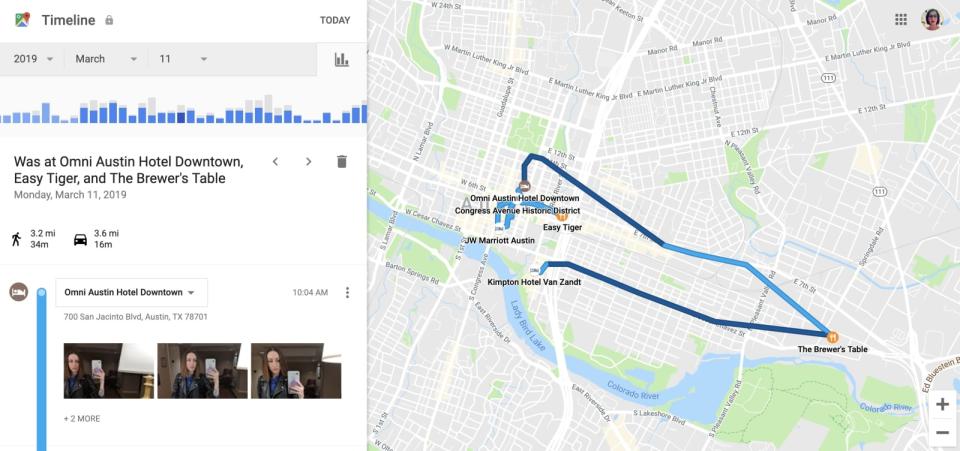

Serial aired in 2014 and it covered a case from 1999. The podcast To Live and Die in LA, meanwhile, began airing on February 28th, 2019, investigating the 2018 disappearance and murder of an aspiring actress. Its tenth episode, "Blood on the Script," dropped on May 2nd, and it starts with an experiment in ping-based location tracking. The host, Neil Strauss, drives to an undisclosed location and his partner, a private investigator, contacts the service he uses to find people in real-time.

The result he gets is wildly inaccurate -- 21 miles away from Strauss' actual location, or one hour and 12 minutes in LA traffic. Strauss then reveals he has access to the suspected murderer's Google account, location history and all. Strauss spends the next two episodes retracing his suspect's steps on the likely night of the murder and over the following days, minute by minute and mile by mile.

In the dead of night, the suspected murderer wove a confusing path around a neighborhood he supposedly knew well, before driving down a small back road that led to the river where the victim's body was eventually discovered. He drove to a Chevron station, and then to a Super8, and finally at 4:04AM, he stopped at a La Quinta Inn. The next day he visited two different car washes, went to his dad's house, and hit a series of stores in a squalid town off the highway. The Google Location History data is so exact that Strauss can see whether the man got out of his truck at each stop.

Strauss follows the friendly blue line across the map, stopping where his suspect stopped and noting how long he spent in each location. He can see his suspect's every move, as long as his phone was connected to Google services.

The gap between Serial and To Live and Die in LA is jarring. Koenig had to guess where her mark might have been within a 20-mile radius at any time, making it nearly impossible to corroborate or refute witness statements, while Strauss was able to see his suspect's precise movements for days on end, complete with timestamps and cute icons.

Google Location History is an investigator's dream, and law enforcement is definitely taking notice. Federal and regional authorities around the United States have been tapping into Google's location database since 2016, using "geofence" warrants to request information on every device that entered a specific location at a certain time. The data points are anonymized -- at least until authorities have enough of a case to compel Google to share the personal information of likely culprits.

It's not a perfect system. Geofence warrants have already led to wrongful arrests; after all, Google is tracking a device, not an actual person. If someone takes your phone on a bank heist and law enforcement throws down a geofence warrant, your data is heading into the war room.

Police and federal investigators are using geofence warrants with increasing regularity. In April, The New York Times reported Google received as many as 180 requests from law enforcement a week. And, if you're interacting with modern society and technology, it's tricky to avoid Google's dragnet.

"We feel so privileged to be developing products for billions of users, and with that scale comes a deep sense of responsibility to create things that improve people's lives," Google CEO Sundar Pichai said during his opening monologue at the I/O conference in April.

Billions of people are tapped into the Google ecosystem, many of them relying on these services daily, or even hourly. While Google's stated mission puts humanity first, its nature as a public entity means executives can't value philanthropy over profit. And, of course, Google makes a lot of money through data-driven ad sales. Advertising alone brought in $30.7 billion for Google in the first quarter of 2019 (the company's overall revenue for the period was $36.3 billion).

More than $10 billion a month is plenty of incentive for Google to collect as much data from its users as possible, consequences be damned. It's the likely reason Google has locked its data-consent policies behind multi-step processes, or forced its apps onto Android phones, or engaged in abusive advertising practices, or offered ads targeted by hate speech. Futureproofing its data-collection abilities could explain why Google hid a microphone in the Nest Secure. All of these incidents were in service of, or a result of, Google's vast internal datasets.

Google rolled out Location History in 2009, and since then, the company has been gathering information on Android and iPhone users alike, even when they've opted out of tracking. A 2018 investigation by the Associated Press revealed Google apps were storing a user's time-stamped location data, even when that person turned off Location History. Google admitted to this practice, telling The Verge, "We make sure Location History users know that when they disable the product, we continue to use location to improve the Google experience."

At this year's I/O, Google emphasized its commitment to privacy. The company has rolled out a handful of new security features, including the ability to auto-delete activity data and Location History on a rolling basis. It's unclear how this feature addresses location tracking in the background of Google apps.

In Engadget's coverage of geofence warrants, associate editor Jon Fingas made the following observation: "Location History's existence isn't a secret. It's been available since 2009, and you have to grant permission before Google starts collecting data. However, people don't necessarily realize that Google keeps the info for an indefinite period, or that the history is detailed enough to provide a picture of street-by-street movements to investigators."

In the name of data-driven profit, that's exactly how Google wants it.

It's been 10 years since Google flipped the switch on Location History, and this sea of information has carved our current reality, where a podcast journalist can log into a Google account and trace the explicit movements of a stranger accused of murder in California, all from the comfort of his own cell phone. This is just a taste of the influence and insight that Google has over the lives of billions of people; it's exhilarating and terrifying.

It also makes for a good podcast.