The Netflix business model is bad news for indie games

Subscription services change everything.

The Netflix model doesn't work for video games. Neither does the Spotify plan, the HBO Go ecosystem or the Amazon Prime Video marketplace. Sure, digital distribution is king and subscription-based streaming services will absolutely become a dominant market force in gaming. But, when it comes to paying content creators, current subscription models just don't make sense. Especially for indie games.

Let's run with the Netflix example. The company acquires shows and movies in licensing agreements based on contract length, exclusivity and an estimated cost per hour viewed. Netflix pinpoints this final figure by tracking audience habits and predicting the number of hours each project will likely be watched during the timeframe of its contract.

A minute-based accounting system may work for a medium with a single, passive input method -- viewing -- but it falls apart when applied to games.

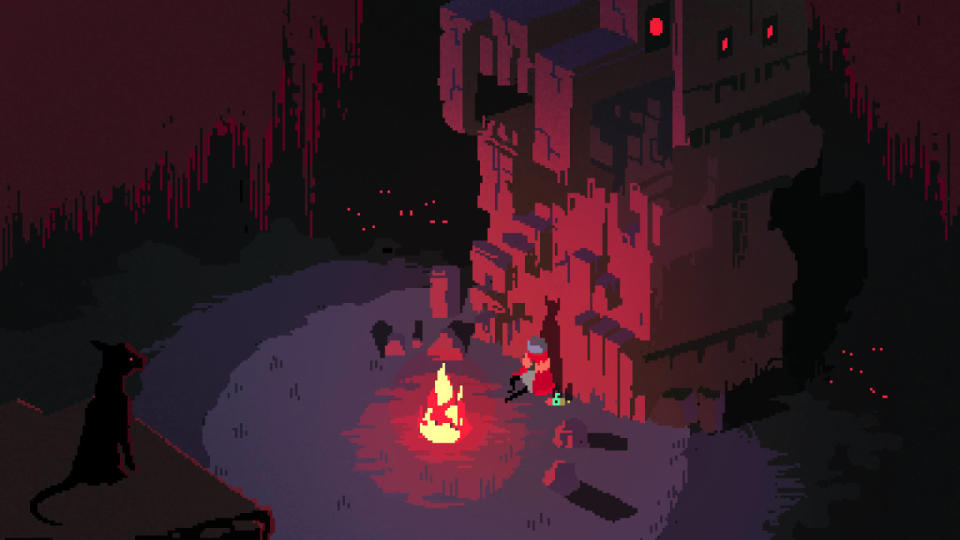

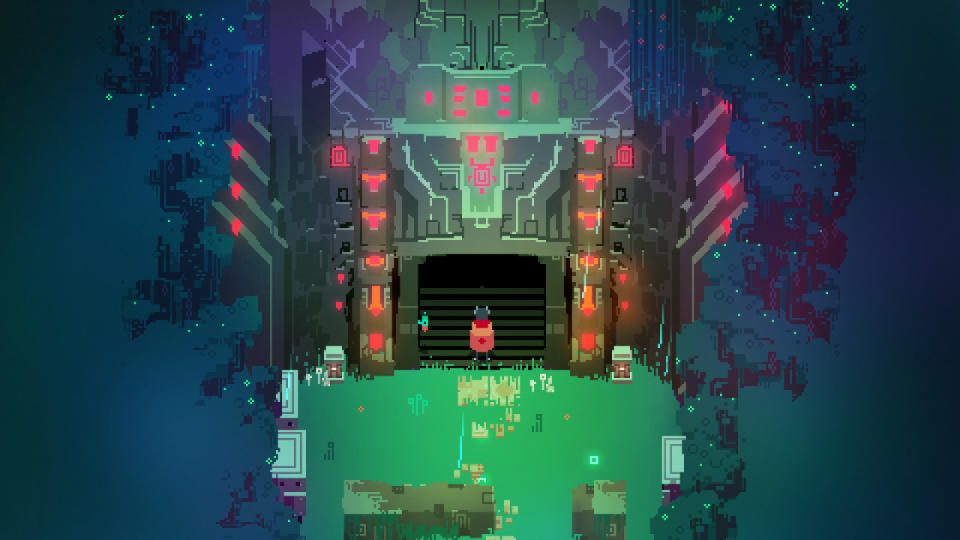

"Pay-per-play is really bad for short games, and so I hate it," Hyper Light Drifter developer and former Square Enix creative director Teddy Dief told Engadget. "I want it to walk away into the sea and stay there. If developers are paid per minute of play, longer games and replayable games make more money, whereas single-play games, especially games focused on authored story, get a raw deal."

Relatively short, narrative experiences are indie games' bread and butter. A bulk of the market's most acclaimed titles are harvested from this genre -- Gone Home, To the Moon, 1979 Revolution, Night in the Woods, Oxenfree, Undertale, Her Story, Firewatch, What Remains of Edith Finch -- and they've helped drive video games into mainstream conversations about art, digital immersion and social justice.

"Pay-per-play is really bad for short games."

Setting narrative aside, most indie games are inherently shorter than AAA blockbusters because they come from smaller teams with vastly fewer resources. Red Dead Redemption 2, for instance, was designed to take 60 hours to complete, though it required hundreds of millions of dollars, and hundreds of people, to create (and there was still crunch). Meanwhile, last year's Best Independent Game at The Game Awards was Celeste, which takes about 10 hours to finish and was built by a handful of people on a budget of thousands.

The indie scene is also where developers go to craft their pet projects, experiment with new ideas or tell specific, contained stories -- all of which leads to a lot of 10-hour games. And less overall playtime, translating to a bad deal for developers on a cost-per-hour contract.

Digital distribution isn't a new idea for video games. Storefronts like Steam and GOG have been tinkering with the formula for more than a decade, and the landscape is still shifting today with newcomers like the Epic Games Store and itch.io. Developers expect more than ever from platform holders, including a favorable revenue split. Steam, the App Store and Google Play taught the industry all about oversaturation years ago, and this possibility will be on the forefront of developers' minds as streaming marketplaces form. They'll want to make sure their games are actually visible to the people who might be interested in them. Apparently, Netflix is still learning this lesson.

"We're lucky as games creators to have leverage in our industry, and I hope our relationship with platforms matures positively and empathetically," Dief said. "We have to weigh not just what a deal means for our team, but the precedent it encourages for our fellow creators. The platforms have more money and power than we do, but we control the art."

Subscription programs aren't a new idea for the industry either, but they'll be critical in the coming generation, which is being founded on streaming and all-digital gaming. Google's ambitious game-streaming service, Stadia, goes live in November; meanwhile, Microsoft is starting to test Project xCloud and it already has a fully digital, disc-less console on the market.

Subscription services like Xbox Game Pass, Google Stadia, EA Access and PlayStation Now will be the backbone of these programs. They each currently offer discrete agreements with developers, determining the value of individual games based on a secretive mix of metrics.

"While we don't talk about the specifics of our business relationships publicly, we can confirm we support our development partners in Xbox Game Pass beyond the licensing fees they receive, and ensure they are compensated fairly for having their games available to Xbox Game Pass members," ID@Xbox head Chris Charla told Engadget.

Xbox Game Pass offers a library of more than 100 downloadable games for $10 a month, or $15 when bundled with Xbox Live Gold. EA has a similar, if not smaller, program with Access, granting members discounts on games and opening up a vault of back catalog titles for $5 a month. On both of these services, players clock more gaming time, they spend more money and they're more comfortable exploring titles outside of their comfort zones -- like moody, narrative-driven indie games.

"Xbox Game Pass has been a great place for narrative games and short-form games to find an enthusiastic audience," ID@Xbox head Chris Charla told Engadget. "I think the fact that we're seeing teams make second, third, and fourth games available with the service shows that developers are pleased with their Xbox Game Pass experience, and our own data shows Xbox Game Pass is an additive tool for trial and discovery of games."

"Xbox Game Pass has been a great place for narrative games and short-form games."

Game Pass members play nearly 40 percent more games than non-subscribers, and the number of genres they try out rises by 30 percent, according to planning and business development head Matt Percy (as reported by Variety in February). Subscription services are great news for indie discoverability, even if the impact on developers' bottom lines remains inconsistent across platforms.

Dino Patti, a co-founder of Inside studio Playdead, described the situation on a Gamelab panel this month, as reported by Eurogamer: "Consumers want as many games as possible, as free as possible. And you can't get anything for free, so you need to find the right price, but that's the angle. ...I've been suggested subscription [and] it's never worked out, because they don't know what developers need, and in the end, it is developers putting out a game for free."

Larger studios and publishers have less of a problem with a pay-per-minute model, since it better serves their interests. Paradox Interactive Executive Chairman of the Board Fredrik Webster said the following during that same panel (as reported by Eurogamer):

"OnLive, for example -- they said you can have your game on our service and we're going to attract a lot of customers, and we're going to deliver you money based on how many hours people play the game. Now at Paradox, we loved that business model, because people play our games for three or four thousand hours. While the Game Pass model to us is still a decent model, we think we're not getting paid enough, because people play our games more than they play very single-player driven narratives."

One point of leverage that developers have in contract negotiations is exclusivity. Creators can charge a distributor more if they promise to sell their game on one platform only, at least temporarily. This serves indie developers well.

"My hope is that as streaming platforms fight to acquire exclusives, they value shorter games," Hyper Light Drifter's Teddy Dief said. "Subscription platforms are a wonderful way for people to discover new types of art they'd never try otherwise. I listen to all kinds of wild music because it's 'free' to me on Apple Music or Spotify, and I've watched some bizarre niche films on Netflix I wouldn't otherwise have bought standalone. This gives developers a chance to be discovered by new audiences."

Exclusivity is a strong bargaining chip for developers, but it complicates things for players. Scattering games across disparate streaming services means players have to pay for a handful of subscriptions per month. The subscription-TV world operates in a similar way now with Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime Video, HBO Go, HBO Now, HBO Max (yikes), and countless other digital subscription services offering their own, exclusive, award-winning wares.

These agreements erect a solid wall between platform holders like Sony and Microsoft, who have a long history of battling for content rights. Ironically, subscription-service exclusivity comes at a time when streaming has the potential to connect players in unprecedented ways, enabling cross-platform connectivity. It feels like a step backward to build barriers between these platforms -- but hey, that's competition.

"How this shapes up depends on the people running these streaming platforms for Sony, Microsoft, Apple, Google, and their foresight and respect for games of all sizes," Dief said. "It'll be up to them and up to us developers as we negotiate deals with these platforms."

A lot of details are up in the air, when it comes to subscription deals in the coming gaming generation. Indie developers are at the forefront, negotiating their games away, and hopefully getting plenty in return.