The new space race is postponed until 2018

Boeing and SpaceX have struggled to get people into space this year.

Aboard the International Space Station, an A4-size flag of the United States hangs next to a 1:100 model of a space shuttle. The memento, placed there by the last crew to fly on shuttle Atlantis, is meant to be retrieved by the next batch of astronauts that launches on a US spacecraft. NASA had hoped to reach that goal in 2017 after awarding Boeing and SpaceX billion-dollar contracts under the Commercial Crew Program (CCP). However, the road back to manned missions is paved with thorns and technical challenges. We certainly won't see any astronauts ferried to Low Earth Orbit before the year ends, but both companies believe that 2018 is the year that flag will be returned to Earth.

The contenders

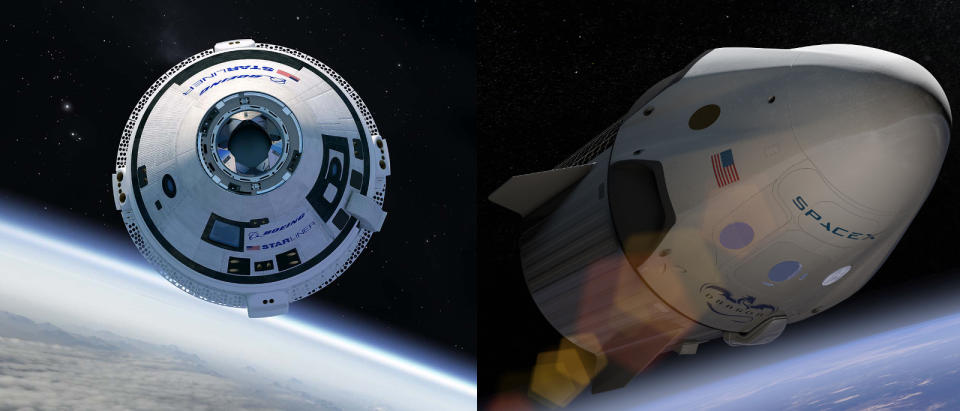

By awarding two companies contracts under the same program, NASA kicked off a new kind of space race. In one corner, we have the SpaceX Crew Dragon, a successor to the original Dragon capsule it's been using to deliver supplies to the ISS. The seven-seater vehicle appears to be quite the looker, with fairly large windows to give passengers a stunningly clear view of their journey -- a feature you'd definitely appreciate if you were a paying customer. The company already has a solid idea of what to do with the capsule outside of its Commercial Crew responsibilities. In fact, it already sold two seats to take private citizens on a trip around the moon next year ... but only if it has already started taking astronauts to the ISS for NASA.

In the other corner, we have Boeing's CST-100 Starliner, which the company has been working on since 2010. Boeing has three different types of Starliners in production, each serving a different purpose. Starliner 1 will remain Earth-bound, specifically designed for ground testing. Its sibling, Starliner 3, will blast off to space for the capsule's first unmanned orbital mission to the ISS. That leaves Starliner 2, which Boeing intends to use for its first manned-flight test.

Both commercial crew partners were on track for a 2017 launch at the beginning of the program, but by the end of 2016, they admitted that they wouldn't be able to stick to their original schedules. NASA had to purchase additional seats on Russian Soyuz rockets for late 2017 and early 2018 to make up for the delay. While it's unfortunate that NASA can't end its reliance on the Russian space agency Roscosmos just yet, the companies had valid reasons to adjust their calendars.

Boeing had to push back its timeline because a Spacecraft 3 dome was damaged during the manufacturing process. Rebecca Regan, the company's Commercial Crew communications specialist, told Engadget that Boeing needed time to identify the root causes of the damage as well as find solutions for it. The company is now looking to launch its first unmanned orbital test flight sometime in the third quarter of 2018; its first manned flight with two astronauts onboard is slated for the fourth quarter.

Things weren't any easier for SpaceX. It, too, was forced to delay its first CCP flights after a Falcon 9 exploded on the launch pad in 2016. SpaceX needed more time to assess the rocket and to investigate the incident with government authorities because Crew Dragon will blast off from a modified Falcon 9. If things go more smoothly for Elon Musk and his team going forward, an unmanned Crew Dragon will be zooming toward Low-Earth Orbit in the second quarter of 2018, while a crewed mission will follow in the third quarter. Both companies will be sending two astronauts to the ISS for their tests flights, which will last for 14 days.

2017: Tests, tests, tests

Because the partially reusable space taxis will carry cargo far more precious than dehydrated food and science experiments, NASA and both aerospace corporations have made safety their top priority. They put their vehicles through some rigorous testing over the past year, pulling no punches to ensure their creations can withstand the stress of spaceflight. One of SpaceX's most notable tests in 2017 involved engineers sealing themselves inside a Crew Dragon prototype to evaluate its life-support system. While inside, they assessed the temperature, carbon-dioxide levels, oxygen levels and cabin pressure, all in an similar environment to what astronauts would experience in flight.

Boeing's Starliner had a tough time as well. The company performed one drop test after another in 2017. It dropped the Starliner on dry soil and wet soil to see how either condition would affect landing. It also examined how touching down on land will affect astronauts' head, neck and spine by loading the test vehicle with crash dummies. And even though Starliner was designed to land on solid ground -- Crew Dragon, by contrast, will land on water -- it also conducted water-drop tests to make sure that it could withstand an abort scenario.

Regan said Boeing pushed its spacecraft to the limit during those tests, proving that its airbag and parachute-landing system works as a result. Back in February, The Wall Street Journal revealed that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) "raised questions about the status of tests" designed to determine the reliability of Boeing's parachute-landing system in its report about the CCP recipients.

In the same report, the department warned that Falcon 9's turbine blades suffer from persistent cracks -- a major threat to rocket safety. SpaceX struggled with that problem for months, even years. Eva Behrend, the company's representative, explained to Engadget that the private space corporation ultimately had to modify its engine design to avoid turbine wheel cracks altogether.

Despite all those successful tests and design changes, a report recently published by The Wall Street Journal says that experts are still worried the capsules won't reach the safety levels NASA demands. The agency apparently imposed a new standard that requires the companies to meet a statistical limit of no more than one possible fatal accident for every 270 flights.

That sounds dangerous compared to airplanes' safety rate of one accident for every million departures. But the technical difficulties associated with manned missions are so hard to overcome that one accident for every 270 flights can be considered safe. NASA's own space shuttle had a safety rate of one fatal accident in 90 flights, and it killed more people than any other space vehicle.

One of the biggest safety threats Boeing and SpaceX had to address was space debris. Both have to make sure their capsules are sufficiently protected from orbital debris, tiny meteors and other particles hurtling through space that could cause serious damage. Boeing plans to use 3D-printed plastic components that can endure extremely harsh environmental conditions better than other materials can. According to The Wall Street Journal's report, it also plans to fit Starliner with some Kevlar. SpaceX said it worked with NASA to define the orbital-debris environment in Low Earth Orbit and to conjure up a Dragon design that mitigates risks brought about by being pummeled with flying space rocks.

If NASA itself had concerns about safety, it certainly did its best to hide them: The agency showed tremendous confidence and trust in the program and its participants this year. It promised to award both companies four more contracts after they successfully demonstrate that their vehicles can safely carry humans to orbit. In March, ISS crew members even installed a second dock that space taxis can use when they finally start ferrying astronauts to the space station. That said, the agency is thinking up ways to ensure Crew Dragon and Starliner stay in top shape. According to Tabatha Thompson, NASA Commercial Space Program's communications lead, the agency is evaluating the use of in-orbit inspections for the capsules.

Outside of safety-related tests and regulations for their vehicles, Boeing and SpaceX both showed off their spacesuit designs this year. Between the two, Boeing's blue suit bears more resemblance to astronauts' current fashion choices, though it's 40 percent lighter than NASA's bulky suits and can keep their wearers much cooler. (Here's a little trivia: The suit was modeled by Christopher Ferguson, the last space-shuttle mission's commander and the one who left that historic American flag aboard the ISS. He's now the director of Crew and Mission Operations for Boeing's Commercial Crew Program.)

SpaceX's, on the other hand, is far removed from typical astronaut wear and has a much slimmer silhouette. That's because it's meant to be worn only inside the Dragon and other pressurized environments. It also wouldn't look out of place at a Daft Punk concert.

A post shared by Elon Musk (@elonmusk) on Sep 8, 2017 at 1:04pm PDT

2018: What's next?

Unsurprisingly, before they can get their first flights off the ground, both companies have to put their vehicles through even more grueling tests. In the first quarter of 2018, Boeing will put the spotlight on Starliner's propulsion systems needed to maneuver the spacecraft during its journey. The company will follow that up with a pad-abort test. It will fire Starliner's four launch-abort engines, taking the capsule a mile up and a mile out before it parachutes into the desert.

SpaceX is already making custom-fit suits for the Crew Program astronauts and will continue the suits' qualification and validation testing next year. In addition, it intends to ramp up the testing of the engines that will provide the power that Falcon 9's first and second stages need to be able to reach the ISS. Because it plans to take off from launch pad 39A, the same historic complex NASA used to launch space shuttles, it'll also complete the installation of a crew-access arm at the site.

After they fly astronauts to the ISS for the first time, the companies can start realizing plans outside of their work with NASA. SpaceX, as mentioned earlier, will take private citizens around the moon aboard Crew Dragon and will fly more privately crewed flights in the future. Boeing also plans to sell Starliner's fifth seat to paying customers, whether they're wealthy space fans or researchers sent by their institutions. It sees a long-term strategy in turning the Starliner into a Low-Earth Orbit liner, regularly taking passengers to space and back.

If you were wondering, NASA doesn't have an issue with those plans: It even encouraged both corporations to take on paying passengers to reduce the long-term costs the government has to shoulder. Sure it's already saving billions of dollars by teaming up with private space companies, but saving even more wouldn't hurt. It's already sinking too much money into its giant Mars rocket and capsule, after all, and it's almost always vulnerable to budget cuts.

While we've focused on Boeing and SpaceX, they aren't the only ones working on human-rated spacecraft. Sierra Nevada, a Commercial Crew Program runner-up, is developing a crew version of the Dream Chaser with NASA in an unfunded agreement. Sir Richard Branson's Virgin Galactic is working on SpaceShipTwo, though it'll probably take a while before the vehicle can take tourists to the edge of space. Its predecessor crashed during testing in 2014, which led to its co-pilot's death.

Blue Origin also created the New Shepard launch system with space tourism and research in mind. The Jeff Bezos-owned company recently sent the second version of its crew capsule to suborbital space for 11 minutes with a doll named "Mannequin Skywalker" on board, strapped to his seat right next to a huge window. Unlike the doll, passengers will be able to unstrap themselves to experience zero-g, which should help ensure that the experience is worth the ticket price.

A new kind of space race

The Commercial Crew Program represents a chance for Boeing and SpaceX to make history and has ignited a (possibly friendly) rivalry that now encompasses other projects. Just a few days ago, SpaceX chief Elon Musk dared Boeing to "do it" when the latter's CEO said he's confident that his team can make it to Mars before anyone else can.

Rivalries like this could be a good thing because they tend to give rise to new technologies that can help make life better. The last space race between the US and the Soviet Union, for instance, led to the creation of better artificial limbs, the water purifier, stronger tires, a freeze-drying technique now used for food and the material used in firefighter gear, among many, many others. Ultimately, it doesn't matter who makes it to the ISS first -- we all win.

Check out all of Engadget's year-in-review coverage right here.