Celebrity holograms sketch me out, but are they the future?

A 19th-century carnival technique could be the key to modern telepresence tech.

Roy Orbison has been dead since 1988 but that didn't stop him from going on a North American tour last winter. Nor has it stopped Whitney Houston, Ronnie James Dio and the Notorious B.I.G. -- or at least their estates -- from reincarnating these deceased celebrities as holographic projections. And this is just the start. The technology is already seeping into sports, porn, even political campaigns. But is holographic technology the future of communications and entertainment or is it an exploitative sideshow leveraging the likenesses of dead celebrities for the profit of their heirs?

The holographic entertainment industry is surprisingly young. Neither Pulse Evolution, which owns the rights to Michael Jackson, Elvis Presley, and Selena's holographic likenesses, nor Hologram USA, which owns Billy Holiday and Patsy Cline (as well as Whitney Houston before a contentious 2016 lawsuit), are more than 5 years old. BASE Hologram, which attempted to launch a posthumous Amy Winehouse tour in February, has been around for less than two years.

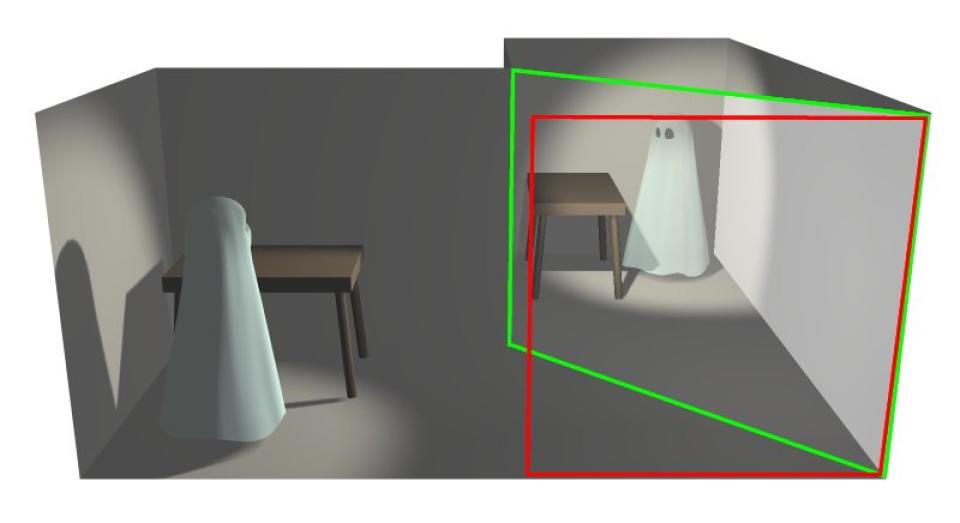

While the current industry is quite new, the technology behind the stage tricks has been around since the late 19th century. The technique is called Pepper's Ghost and was first demonstrated in 1862 by English scientist John Henry Pepper. The trick works by having a second room (dubbed the blue room) set up off of the main stage with a piece of clear glass or plastic separating them. As the lights in the main room are lowered and the lights in the hidden blue room raised, light hitting objects in the blue room reflects off of the clear divider and makes it appear as if the items are floating like ghostly apparitions in the main room. Remember the part of Disneyland's Haunted Mansion when the hitchhiking ghost appears in the ride's car with you? That was the Pepper's Ghost effect.

Pepper's original setup was especially crude, with heavy sheets of real glass and inaccurate lighting making everything appear as though it was called back from the netherworld. Today, however, thanks to 4K (and soon 8K) cameras, LED projectors and super-thin projection foil, the results are startlingly lifelike.

"When you light it properly, when you create content using the highest resolution cameras possible," said David Nussbaum, VP of production at Hologram USA. "An audience member will swear that the thing or the person being projected is actually there."

Pepper's Ghost does have some drawbacks. For one, the amount of space in which objects can be projected is limited. It's not like you can string a sheet of reflective plastic up across the entirety of a stage, Martin Tudor, CEO of BASE Hologram Productions, explained in an interview with Engadget.

"If you have a live band or orchestra on stage, that plastic vibrates from the noise," he continued, not only causing the projected image to blur but also dampen the sound from the orchestra itself. BASE's technology is built on proprietary technology that relies on first finding an actor that physically resembles the celebrity and having them generate "a bank of movements," as Tudor explained to Vox in 2018. In the case of Amy Winehouse, who did not have her face scanned before her death, the company had to painstakingly digitally recreate it.

But just because we have the technology to revitalize dead celebrities as holographic puppets, does that mean we should? Fan reactions to the now-aborted Winehouse tour were mixed when news broke of its production. Some fans saw it as a chance to see their favorite singer perform again, while others viewed it as an exploitative cash grab by her estate. The Orbison tour received similarly mixed reviews, with some critics calling the performance "inauthentic" while others argued that the show exploited a dead singer who could not provide consent.

"Consent for holograms is going to be a hot topic," said Catherine Allen, founder of Limina Immersive, in an interview with The Guardian in 2015. "As long as the person has consented, it's fine. An audience member 'does' an augmented reality or a virtual reality experience rather than watch it. It is important to think about ethics at this early stage of the development of the immersive sector, because it is still relatively new, it is still being shaped. The norms that we create now will set the standard for the future."

Both Tudor and Nussbaum deny claims that the process is exploitative. Nussbaum points out that any and all usage of deceased celebrities have to first be cleared by the person's estate, then the music, likeness and image all have to be properly licensed from their respective studios and publishers. There are a lot of hoops to jump through and a lot people to have sign off on one of these projects before it gets off the ground.

"We rely on these estates," Tudor told Engadget. "They have the rights. They know their artist. They should know what [the artist] likes, what they don't like and what they would want. We rely on them to help us guide us to doing something authentic.

"You know, if they're exploiting their artist, there's not much we can do about it," he continued. "They're the guardian of somebody's legacy."

Troublesome celebrity projections -- yes, even Hatsune Miku -- can be problematic. Nussbaum and Tudor both envision a future where holographic technologies are used for far more than concerts. "In my view, it all comes down to what are you watching?" Tudor asks. He argues that after the novelty of holograms wears off, we'll be left with a viable and valuable communication medium. "I think it's just another form of entertainment and information," he said.

Nussbaum points out that these celebrity holograms will "create a revenue stream for generations and inspire young artists to see their favorite icon potentially long after they're gone."

"That is great," he continued. "But connecting with people from office, by town or even off the world in real time. So live via satellite, live via hologram, that's where we're going."

We're still likely a long way off from Princess Leia-style volumetric holograms. Nussbaum and Tudor are split on its viability: Tudor is confident we'll see them within the next few decades, Nussbaum dismisses the idea as post-production movie magic. However, living artists are already beginning to toy with the idea of global, networked concert performances and politicians are exploring the space as a more convenient and secure means of campaigning around their districts and states. But whether the technology becomes ubiquitous, or just fades into obscurity as 3D TV and smell-o-vision before it, remains to be seen.