Moog Subharmonicon review: An experimental synth with an iconic sound

Inspired by early electronic instruments, the Subharmonicon makes unique music from math.

Moog’s current lineup of semi-modular synths all have cute mother-themed names: Mother-32, Drummer From Another Mother (DFAM), Grandmother and Matriarch. But the newest entry -- the $699 Subharmonicon -- abandons that tradition, even though it’s part of what is officially called the Mother ecosystem. It’s a strange device that indulges its experimental side more than either the Mother-32, and maybe even the DFAM.

The Subharmonicon is largely inspired by a pair of early (and kinda bizarre) electronic music instruments, the Mixtur-Trautonium and the Rhythmicon. Those avant-garde roots show and can make it a bit daunting, especially if you’re just looking for a quick fix of that iconic thick bass. But a little patience and persistence reveal that the Subharmonicon, for all of its complexity, is still classic Moog.

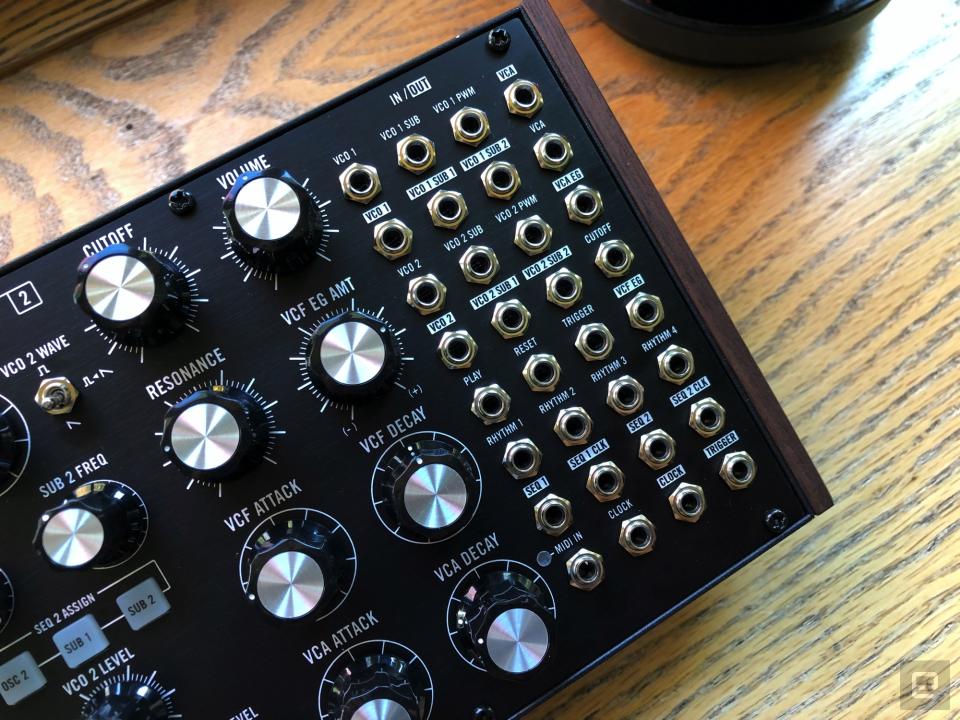

The face of the Subharmonicon can be divided into four sections. First is the sequencer on the left. It has its origins in the Rhythmicon -- widely recognized as the first electronic drum machine -- and is built around the concept of polyrhythms. Then there are the two analog oscillators and their matched pair of sub oscillators inspired by the Mixtur-Trautonium -- an early electronic instrument designed to explore subharmonic undertones. After that are the classic Moog ladder filter and the envelope generators for shaping your sound. Last, there’s the 32-point patchbay on the right, which is a staple of the Mother lineup.

I’m not going to spend too much time covering those last two sections. As much as I love the sound of Moog’s filter, it’s well-tread territory. And the patchbay, well, there’s nothing particularly unique about it. But if it does open up a number of avenues for further tweaking your sound and connecting to other synths and gear.

So let’s start with the oscillators. All of them (the two main and four subs) are independently tunable. The frequency of the subs is determined by taking the frequency of the main oscillator and dividing it by a number from one to 16. When the knobs are turned all the way to the right, they’re in unison with the main oscillator. As you turn them counterclockwise, they generate different subharmonics. Most subs simply play the same note an octave or two lower. So in short, these sound different because math.

This also means that you can use the Subharmonicon to “play” six-note chords with a single press of a button, or key if you connect an external controller. So even though it is in theory a two-voice paraphonic synth, you can get some complex sounds out of it.

You can tune the oscillators in a completely unquantized mode if you feel like exploring the world of microtonal music. Those of you with more-traditional tastes will be happy to know that there are four different modes of quantized tuning. There are twelve- and eight-note versions of both equal temperament (the standard for modern Western music) and just intonation. And you can set the range of the sequencer knobs to be plus or minus one, two or five octaves from the oscillator’s frequency. Picking plus or minus five will give you a total of 10 octaves to explore. This is at the expense of accuracy, since you’ll now have 120 notes to choose from as opposed to 24 in one-octave mode.

There are also three options when it comes to wave shapes: square, saw or a combination of a square main oscillator and sawtooth subs. That gives you access to not only classic Moog bass but also brassier tones and rich multitimbral sounds. Using the patchbay, you can also feed one oscillator into another to create metallic FM tones, a noise source or modulate the pulse width of the main oscillator, which is great for adding a bit of dissonance or warbling your sound.

This is all to say that while the name and spec sheet might lead you to believe this synth is all about the bass, it’s capable of a wide range of timbres. In fact, within an hour of unboxing the Subharmonicon, I was coaxing some rather lovely pads out of it. And with a little clever patchbay work, you can even get some solid drums.

When I eventually figured out how to get some respectable percussion sounds going (it took a couple days), I was pretty excited, in large part because of the potential for pairing them with the sequencer. Or should I say sequencers. There are two of them: one for each of the oscillators. At first glance it might not seem like much -- a pair of four-step sequencers -- but this machine has a lot of tricks at its disposal.

The most powerful tools are the rhythm generators. Similar to the sub oscillators, these divide the master tempo by a number from one to 16 and then apply that to the sequencers to create polyrhythms. All four generators can be applied to sequencer one, two, both or none. This means that even if you’re limited to only four notes, the rhythm at which they play and the way they combine can create long, evolving passages that might not repeat for quite some time.

For an extremely simple example of this, you could set sequencer one to play a four-note progression, stretched out over four bars. Then sequencer two could play a simple arpeggio twice before the bass note changes, creating a shifting harmony that feels much longer than what you could get out of a standard step sequencer.

Now, it’s important to note that the Subharmonicon is paraphonic -- which means the oscillators share a single amp envelope and filter envelope. So when the sequencer triggers one voice, both sound. This means you can’t really have a slowly plucked melody playing over a constantly thumping bassline without some patchbay trickery (or external modules). This is a shame, because being able to trigger the oscillators separately would open up whole new avenues for rhythmic exploration. But there are still plenty of opportunities for them to interact in interesting ways.

Like many synths, the Subharmonicon really shines when paired with some effects pedals. Here it’s run though various combinations of delay, reverb and distortion to show how they can greatly expand its character.

The other major tool at your disposal is the ability to choose which oscillators your sequencers are controlling. By default, sequencer one is for oscillator one and sequencer two is for oscillator two (you can’t use both sequencers to trigger a single oscillator). But you pick whether the sequencer controls the main oscillator, sub oscillator one, sub oscillator two or some combination of the three. When the sequencer is controlling the sub, it’s changing its relation to the main oscillator, not controlling its frequency directly. This can result in some really out-there sounds. You can have the main oscillator chug away while the sub dances around it. Or as the main oscillator changes, the subs can shift the interval they’re playing.

If you’re anything like me, your first instinct will be to get everything going at once: all four rhythm generators triggering both sequencers, which are controlling both the oscillators and their subs, with everything tuned to different intervals. Allow me to tell you right off the bat: This is a terrible idea. While it’s tempting with any new toy to use all of its fancy features, restraint is the key to making the most of the Subharmonicon. It is incredibly difficult to get all six voices to line up in a consistently pleasing manner if you’re using the sequencers to control all of them. Since the voices are all triggered simultaneously, the line between interesting interplay and complete chaos -- if you use all four rhythm generators simultaneously -- is very, very thin.

That fine line between interesting and disastrous can be difficult to navigate at times, especially with the tiny knobs on the sequencer and rhythm generators. Just like the Mother-32 and DFAM, the Subharmonicon is a compact synth. And it has a lot of controls on its front. That means some of them can be a bit fiddly and frustrating. However, if you’re patient and resist turning knobs with abandon, you’ll be able to find the rhythms and notes you want.

It’s not like those tiny knobs feel cheap or seem in any danger of getting loose and wobbly though. This isn’t a disposable Pocket Operator. In fact, this is one of the more solid-feeling pieces of musical hardware I’ve had the pleasure of playing. The knobs all have a satisfying amount of resistance, and the combination of metal and wood has a charmingly retro feel to it. The materials also give it a decent amount of heft. Something like Korg’s Monologue is also made of wood and metal and has a similarly old-school vibe, but it’s surprisingly light. The Subharmonicon, on the other hand, feels like it could be used to assault someone.

Moog enlisted synth icon Suzanne Ciani to create a composition using only the Moog Subharmonicon to celebrate its launch.

Of course, whether or not a synth is well suited to bludgeoning a person shouldn’t factor into your buying decision. It’s about how well it will fit your musical needs. If you’re into creating more-experimental styles of music and frequently use polyrhythms, then there’s a compelling case to be made for the Subharmonicon, especially if you have other modular or semi-modular gear to pair it with. If you’re looking for your first semi-modular synth, however, there are more-logical choices.

While you can certainly dial in a classic Moog bass sound and connect a MIDI controller to the Subharmonicon, that would be a waste of its more unique features. And you could at least approximate some of the more traditional sounds on tap here from something like the Arturia MiniBrute, the Korg MS-20 or the Behringer Neutron. Those first two have keyboards while the latter is cheap enough that it borders on impulse purchase. (However, Behringer’s ethics are often questionable.)

That being said, if you want the classic Moog sound but don’t need the more experimental sequencing and subharmonic-generation features, the Minitaur or Mother-32 are probably your best bet. The former is significantly cheaper at just $399, but it’s more limited from a sound-design perspective. There’s no sequencer or patchbay either. The Mother-32 is roughly the same price as the Subharmonicon at $649, the same size and has many of the same core features, including that filter. But it offers a little more room to explore than the Minitaur.

The Subharmonicon is best suited as an expansion to an existing setup rather than as the start of a collection. It sounds amazing -- like, truly amazing. And the unique sequencing capabilities are like nothing you’ll find on a mainstream instrument. But it’s also clearly a niche device. It’s not going to appeal to every musician or synth nerd. But those who find their interest piqued will probably be enthralled.