'Breath of the Wild' is the best 'Zelda' game in years

If this won't sell systems, nothing will.

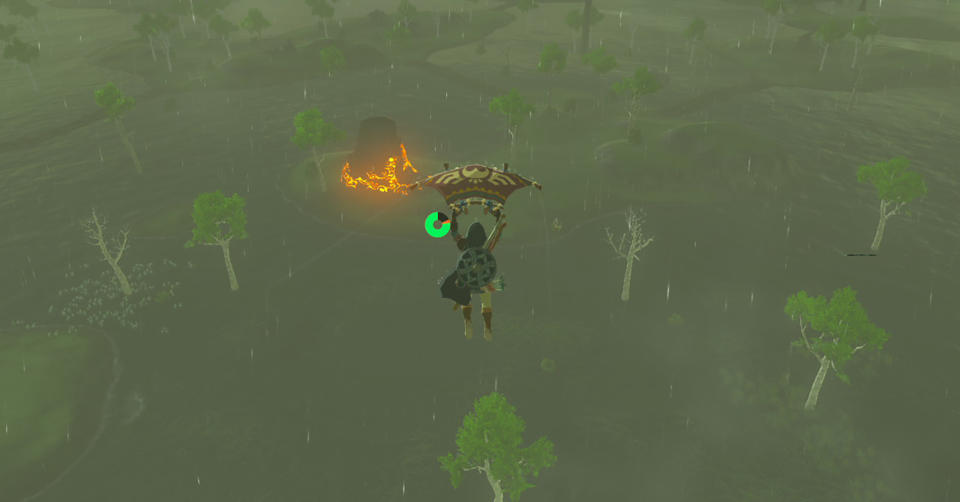

I replayed the first 30 minutes of Rise of the Tomb Raider the other day. In it, I scaled a mountain, leaping from platform to platform while the environment around me crumbled. I then headed into a tomb, worked through a few puzzles, and triggered a high-octane escape sequence. A year ago, I enjoyed those opening moments immensely. After playing The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, though, they felt lifeless and stale. From Tomb Raider to Uncharted, the modern adventure game is a tightly choreographed charade, a 20-hour quick time event (QTE) with a clearly defined path. When I jumped to evade an avalanche, Lara landed exactly where the game's developers wanted her to. When I needed to solve a puzzle, the game began pointing, beckoning me to do what the developers wanted me to do. In Breath of the Wild, I had heart-stopping, adrenaline-filled moments, I solved complex puzzles, but through it all, I walked my own path. The Zelda series has long followed a simple pattern: You awaken as Link, the silent protagonist, and find a sword and shield. Then you discover that a mysterious antagonist is messing up the fictional land of Hyrule. You must, of course, save the kingdom and its Princess Zelda, so you travel to a number of dungeons, each holding a key item that will aid you on your quest, and defeat the bosses within, before facing off against the big bad. Day saved. Roll credits. While there's still a lot of that DNA in this game, the development team has thrown out some old ideas completely. And those tropes that do remain have been disguised and evolved, leaving a game that feels fresher than I'd ever imagined a 31-year-old franchise could. Take our hero, Link. He begins as a silent soul, almost devoid of life, but through the course of the game he uncovers facts about his past that build him out as a character. The narrative is structured around him, and the journey it sends you on feels natural and logical. Sure, there's a lot of talk of destiny and heroics, but when on the main quest, I felt a sense of purpose, a notion that I wasn't striding down a well-trodden road, but finding my way on a Tolkienesque journey. The world of Breath of the Wild is enormous. Link begins his adventure on a plateau -- a kind of tutorial area, but without the tutorial. You very quickly meet an old man who recalls the first NPC Link ever met, in the original NES classic. He sends you on a mission to find Shrines -- essentially single-room puzzles littered throughout the world -- promising you a glider in return, and with it a safe way off the plateau. The first Shrines you come across are very simple, serving more as a conduit to grant you a set of powers that you'll use throughout your quest. These come in the form of Runes, and the important ones let you set bombs, manipulate metal objects, turn water into ice or temporarily freeze an object in time. They're useful in combat, and essential to beating the other Shrines (there are 120, and completing them gives you additional life and stamina) and the more complex challenges that lie ahead. Rather than hand you specific items at the right time and tell you what to do with them, as past Zelda titles did, Breath of the Wild dumps a lot of skills on your lap at the start of the game. It's up to you to work out which tool works in which situation. Because of this lack of linearity, finally cracking a puzzle brings a sense of accomplishment that's been missing from almost every Zelda game in recent memory. From the moment you receive your first quest, it's clear that something's different here: You're not given waypoints. To aid your search, Link has a tablet (called a "Sheikah Slate") that can act as a map. You start the game with that map entirely blanked out, save for the boundaries between regions, but if you can see a place in the distance, you can mark its location with the slate. Your task, then, is to head for high ground, try to spot the Shrines, and find a way to get to them. Eventually, you're given a simple warmer/colder tool to help you track down Shrines, but wayfinding still forms a huge part of Breath of the Wild. By being vague about locations, and the paths thereto, the game asks you to explore, and to adapt. Upon leaving the plateau, I headed, as instructed, to Kakariko Village to talk to the next quest giver. It was on that walk that I allowed myself time to slow down and really take the world in. While there are clearly more technically proficient games out there, the art direction in Breath of the Wild surpasses anything I've played before. The Switch's screenshot tool doesn't quite do the game justice, but the presentation here is pristine, with gorgeous character and location modeling, smooth animations and dazzling particle effects. That journey to Kakariko sticks in my mind almost as much as entering the village itself. Perhaps the biggest leap forward over past Zelda games is the lighting. The way the mood changes with the weather and time of day is stunning, and I don't think I'll ever forget the first time I got caught in a thunderstorm. But even now, some 45 hours later, I find myself stopping and pausing to take in a sunset, or even just the shadow of a cloud rolling across a field. While that initial trail followed a fairly straight road, it would be the last time I was handed such a simple objective. Missions sometimes place a waypoint on your map, but they give you little indication of how to get there. Instead, I found myself reading signposts to find my way. Even then, the world is full of environmental obstacles, from rivers and mountains, which simply need traversing, to lava and snow, which require special clothes or elixirs to deal with. Heading in a straight line toward an mission will rarely work out well, and as roads frequently diverge, it's tough to stay on the right path. To aid in your travels, there are various towers dotted around the landscape (one for each of the game's regions). Finding a way to the top of these structures is not always simple, but when you finally reach the summit you'll be rewarded with a map of the corresponding area. The changes continue into combat and inventory management, both of which have been thoroughly revamped. The basic combat controls will be familiar, but the biggest change is that weapons slowly degrade as you use them, before eventually breaking. This mechanic adds a new dimension to encounters: You could certainly attack every foe with your best weaponry, but what happens when it falls apart and a difficult enemy appears? Invariably, you die. As such, you'll want to approach each battle with careful thought. There are Rune skills that could dispatch a beast or two; you could use stealth to sneak up on a watchman, or take someone out from afar with a well-placed arrow to the head. And you'll want to check every weapon an enemy dropped to see if it's of use. Weapons also handle fairly uniquely. Obviously, swords are different from spears, and boomerangs are different from bows, but there's a sense of weight, and a real physics engine driving combat here. Heavy swords swing slower than light ones, making them tricky to wield successfully against a fast opponent; arrows travel in an arc, making aiming at a distance hard; and the boomerang, although difficult to master, is extremely satisfying when you get it right. There isn't a huge range of enemy types in the game, but what variety is there is augmented in some intelligent ways. There's a real sense of dynamism from the combat, and environment plays a key part in every battle. Enemies can be intelligent, and adapt quickly. The addition of a stamina meter also brings something new to combat. In a typical encounter, it doesn't come into play; unlike in Dark Souls, it's virtually impossible to tire yourself out just by swinging your sword around. But running, gliding and climbing will all have Link gasping for breath. In one moment, I was fighting a group of three Lizalfos (twitchy, bouncy, lizard-like enemies). I approached from the air, gliding over before shooting an arrow at one of their heads. I then descended quickly, smashing that enemy with an ax as I touched down. From there, I switched to a boomerang. I hit the second Lizalfos, but I mistimed the button press to catch the weapon on its return. As I raced over to retrieve it, I ran out of stamina. One of my foes quickly grabbed my boomerang and began attacking me with it. I did not survive the encounter. As with all good games, every time I died I knew it was my fault. At least at first, though, some battles felt unfairly weighted against me. Roaming the land are Guardians, dangerous mechanical sentries that you'll certainly bump into. They move faster than Link can on feet, their attacks have a longer range than yours and, honestly, they're kind of terrifying, even with the necessary equipment to fight them. I've been killed by them countless times, and I've died in this game maybe 30 times total. That's probably more deaths than my combined count across all Zelda games in the past 15 years. So staying alive is hard, and I get used to seeing "Game Over" fairly frequently. While it doesn't come close to testing you in the way that, say, a From Software game would, Breath of the Wild is not an easy game. Like in Dark Souls, simple enemies can quickly overwhelm you if you approach them incorrectly. Because of this, maintaining and managing your inventory is key. There's a bona fide in-game economy now, along with a fairly robust crafting system. There aren't many rupees lying around on the floor, so you'll need to do more to make your way through Hyrule. Upon death, enemies "drop" various "items" (i.e., you pick up a few of their body parts), which can either be used to craft elixirs or sold to stores and traveling salespeople. You can also harvest vegetables and fungi, and hunt fish and mammals for meat. Oh, and there are various critters around the world that make an excellent addition to an elixir. Crafting is done at campfires: You combine ingredients to create dishes that not only recover health but increase your attack power, stamina, defense, or environmental resistances. The crafting system is a welcome addition, but it's not without issues. Cooking up one of these meals takes no time at all, but preparing 30 dishes can be a slog. You have to manually head to your inventory, pick up a steak, back out of the menu, and drop the steak into the pan. Over and over again. Nonetheless, it became something of a ritual for me to cook up various meals before sending Link to sleep, ready for a long journey in the morning. It took me around 45 hours to beat Skyward Sword, the last home console game in the series. I've put almost exactly that much time into Breath of the Wild and, so far as I can tell, I'm barely past halfway. That's partly because this is the biggest game Nintendo has ever made, but it's also because Zelda just begs you to explore. The game's real genius lies in its map. It's vast -- more akin to The Witcher 3's than Skyrim's in size -- and it's full of life. Even its quieter sports are crafted in such a way that they feel connected to the overall world. Heading from one location to another, you invariably see points of interest in your peripheral vision. Typically, this is achieved by elevation. Say you're heading along the side of a canyon, when suddenly the mist parts to reveal an oasis below -- who wouldn't want to glide down and take a look? Other times you'll see a distant spec moving on the horizon (draw distances are stellar), or a Shrine nestled on a hilltop. Remember: Anything you can see, you can mark as a waypoint on your map, which made finding my way around the world feel like a much more personal effort. I've spent days of in-game time carving a path through the game's various areas, just on the whim that I might find something worth doing at the end of my journey. Almost without exception, the game rewarded my exploratory instincts with items, characters, new locations, or, occasionally, just a beautiful vista. The consistency of these reward loops encouraged me to explore more, to find high ground, to head to the farthest point I could see. It's at these moments, when I'm scaling a sheer rock face in the hope of discovering something at its peak, that the game is at its best. Throughout it all, music is sparse, which lends a real sense of isolation. Occasionally, you'll hear some incidental piano playing in the background, while combat also triggers some light music, but the rich orchestral scores of Ocarina of Time are nowhere to be found here. It's mostly just silence, or the sounds of nature. In addition to Shrines dotted all around the landscape, Breath of the Wild has some larger set-piece dungeons, more in the style of the classic Temples of Zelda past. But, like everything in this game, these dungeons are dramatically different from what you've seen before. The larger dungeons are typically introduced by memorable gameplay moments. In one case I found myself firing arrows in midair at a giant beast in bullet time; in another I had to stealthily guide a dumb companion past deadly sentries. Once those set pieces are over, though, you're essentially dropped in the middle of a giant puzzle and asked to work your way out. Once inside, you'll discover there are no keys, no new items and no labyrinthine layout. Instead, they're a single environment, which you manipulate in order to achieve your goal. Rather than handing you, say, a grappling hook and asking you to use it to navigate around a space, the game expects you to use all your Rune skills to proceed to the flashy boss fight that awaits. The second layer of complexity comes from points of articulation within the dungeon. Once you've downloaded its map onto your tablet, you're able to transform the layout slightly with the press of a key. In one example, this might be to change the flow of water to get wheels spinning in motion, while in others, you're able to rotate the entire dungeon on its side. The level of challenge offered isn't off the charts -- although I did get stuck for an hour by missing something blindingly obvious -- but the puzzles really encourage lateral thinking, and required me to use all the tools at my disposal to progress. There has never been this big a change in direction since The Legend of Zelda first graced the NES 31 years ago. Despite rightly being lauded as one of the best games ever, Ocarina of Time was not the sea change that Breath of the Wild represents. Yes, it realized the world of Zelda in three dimensions, and provided memories that will last many gamers a lifetime, but it did not drastically mess with the formula laid down by A Link to the Past in the early '90s. Breath of the Wild does. Nintendo has challenged the very notion of what a Zelda game can be. It's torn out parts I would've considered key to the franchise and swapped in the very best ideas from other titles. Breath of the Wild borrows liberally from games that, in fairness, all owe the Zelda series a little piece of their existence. It takes Far Cry's scouting out locations and hunting animals. It has Monster Hunter's meticulous journey preparation. It distills the sense of wonder you get in Skyrim when you spot a speck on the horizon and resolve to one day see it. There's even a little of Just Cause's physics-based mayhem wrapped in there somewhere. Yet, despite all of this change, I never once questioned that I was playing a Zelda game. It's not just the characters, or the shared world. There's a quality beyond the tangible that makes Breath of the Wild feel like an entirely natural evolution of a beloved franchise. This is a blueprint for a new kind of Zelda game -- one that can undoubtedly evolve and improve beyond our imaginations in the future. For Nintendo to have reworked so much without losing what makes this series so special is an achievement in itself. For it to have created something that, after 45 hours or so, is shaping up to be one of the best games ever made is something else entirely.

New beginnings

Into the wild

A new fight

The joy of exploration

A different kind of dungeon