geneediting

Latest

China detains scientist who claims to have made gene-edited babies

China was quick to halt the work of scientist He Jiankui after he claimed to have created the first genetically edited babies, but that apparently wasn't enough. After weeks of uncertainty surrounding He's whereabouts, the New York Times has learned that the government has placed the researcher under house arrest at a housing facility in the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen. He can make calls and send emails, but he can't leave. Guards prevent people from getting close to either He's de facto residence or the offices involved in his research.

China halts scientist's gene-edited baby research

The scientific community and the world at large were rocked this week when researcher He Jiankui claimed he had created the world's first genetically edited babies. Using CRISPR/Cas9, He says he edited the genes of twin girls, Lulu and Nana, in order to make them more resistant to HIV. But He's work has been met with severe backlash as scientists around the world have called it irresponsible and unethical while emphasizing that CRISPR technology is not yet ready for human embryos since associated risks are not fully understood. Now, the Associated Press reports that China's government has put a hold on He's work.

CRISPR editing may help turn a wild berry into a farmable crop

It can take many years to make a wild plant easy to farm, but gene editing could make that happen for one fruit in record time. Scientists have used genomics and CRISPR gene editing to develop a technique that could domesticate the groundcherry, a wild fruit that's tasty and drought-resistant but difficult to grow in significant volumes. After sequencing the groundcherry's genome, the team both tweaked CRISPR to work with the plant and pinpointed the genes that led to its less-than-pleasant traits, such as its small size and not-so-plentiful flowering. From there, they just had to 'fix' the fruit with gene edits that promoted the qualities they wanted.

CRISPR might cause more unintended DNA damage than we thought

A new study published today in Nature Biotechnology warns that CRISPR may not be the ultra-specific gene editor we've believed it to be. With CRISPR-Cas9, researchers can find particular sequences in a cell's DNA and cut them at a specified spot. The cell can then repair the DNA where it was cut and scientists have been attempting to use this technique to treat all sorts of diseases and disorders including ALS, Huntington's disease, HIV and sickle cell disease. The method has been thought to be rather specific, allowing scientists to target and remove only certain sequences while leaving surrounding DNA intact. But this new study says that CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing might be causing more damage than previously reported.

Scientists reprogram T Cells to target autoimmune diseases

Researchers from the University of California, San Francisco have uncovered a gene-editing technique which could provide safer treatments for patients with cancer and autoimmune diseases. The breakthrough -- which involves the CRISPR/Cas9 system -- will allow T cells (the cells which fire up our immune response) to recognize infections with greater specificity, and eliminate the need to use viruses for transferring DNA to target cells.

Gene-edited rice plants could boost the world's food supply

Rice may be one of the most plentiful crops on Earth, but there are only so many grains you can naturally obtain from a given plant. Scientists may have a straightforward answer to that problem: edit the plants to make them produce more. They've used CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to create a rice plant variety that produces 25 to 31 percent more grain per plant in real world tests, or far more than you'd get through natural breeding. The technique "silenced" genes that improve tolerances for threats like drought and salt, but stifle growth. That sounds bad on the surface, but plants frequently have genetic redundancies -- this approach exploited this duplication just enough to provide all of the benefits and none of the drawbacks.

Recommended Reading: The fate of Facebook's free internet project

What happened to Facebook's grand plan to wire the world? Jessi Hempel, Wired For years, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg touted the company's Internet.org initiative that sought to bring connectivity to everyone in the world. It was presented an ambitious humanitarian effort, but things didn't go according to plan. Wired tells the story of what happened to the project following criticism and bans from local governments.

Researchers use CRISPR to detect HPV and Zika

Science published three studies today that all demonstrate new uses for CRISPR. The gene editing technology is typically thought of for its potential use in treating diseases like HIV, ALS and Huntington's disease, but researchers are showing that applications of CRISPR don't stop there.

First human CRISPR study in the US could begin soon

In mid-2016, A federal panel had greenlit the University of Pennsylvania to pursue the first trials using CRISPR gene-editing in the US. It seems the institution has quietly gotten the ball rolling and could theoretically start the study at any time: A posting was found on a directory of trials describing a yet-to-be-scheduled UPenn survey using CRISPR techniques to treat cancer patients.

Key CRISPR gene editing methods might not work for most humans

At first glance, CRISPR gene editing looks like the solution to all the world's ills: it could treat or even cure diseases, improve birth rates and otherwise fix genetic conditions that previously seemed permanent. You might want to keep your expectations low, though. Scientists have published preliminary findings indicating that two variants of CRISPR Cas9 (the most common gene editing technique) might not work for most humans. In a study, between 65 percent and 79 percent of subjects had antibodies that would fight Cas9 proteins.

Gene therapy gives 'bubble babies' immune systems

Initial results from a new gene therapy technique suggest it could open the doors to a cure for "bubble baby" disease. Lacking the ability to ward off even the most common infections, infants born with the genetic disorder -- known as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) -- usually die before their second birthday. And, those untreated must be kept in isolation from the outside world, hence the term "bubble baby." Even with the best available treatment (a stem cell transplant), around 30 percent of children end up dying by the age of 10.

Scientists make first attempt at editing genes inside the body

Brian Madeux became part of medical history on November 13th after receiving a special kind of IV medication. It contained copies of a corrective gene paired with a genetic tool that can cut his DNA, you see, in an effort to cure a rare genetic disorder called Hunter syndrome. According to the American scientists who performed the procedure, it's the first ever attempt at editing a gene inside the human body.

New CRISPR tool alters RNA for wider gene editing applications

The CRISPR gene editing technique can be used for all sorts of amazing things by targeting your DNA. Scientists are using it in experimental therapies for ALS and Huntington's disease, ways to let those with celiac disease process gluten proteins and possibly assist in more successful birth rates. Now, according to a paper published in Science, researchers have found a way to target and edit RNA, a different genetic molecule that has implications in many degenerative disorders like ALS.

Gene editing technique could treat ALS and Huntington's disease

The most common gene editing technique, CRISPR-Cas9, only modifies DNA. That's helpful in most cases, but it means that you can't use it to tackle RNA-based diseases. Thankfully, that might not be a problem for much longer. After plenty of talk about editing RNA, researchers have developed a new RNA-oriented technique (RCas9) that can correct the molecular errors which lead to diseases like hereditary ALS and Huntington's.

Researchers are trying to make pig organs more viable for transplant

We have a huge supply and demand problem when it comes to organ transplantation. Closing that gap with animal-grown organs is an idea that's been on the table for some time, but it comes with a slew of issues that have prevented it from being a viable option. Pig organs are the right size for human transplants and are similar enough to our own, but pigs have viruses embedded in their DNA that could potentially infect humans and cause serious harm. However, a new study out today in Science shows that with the gene editing tool CRISPR, those viruses can be removed, bringing pig organs one step closer to human bodies.

Artificial skin transplants could be used to treat diabetes

Skin grafts made using CRISPR gene editing are preventing mice from developing diabetes, and scientists claim they could prove beneficial for humans too. In a proof-of-concept study, researchers at the University of Chicago edited stem cells from newborn mice to controllably release glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). This is the hormone that stimulates the pancreas to produce insulin while maintaining healthy levels of blood glucose. The genetically modified skin grafts were then given to mice that were fed high-fat diets to induce obesity. These mice saw a reverse in insulin resistance and gained around half as much weight as those not given the grafts.

US scientists have genetically modified human embryos

A team of scientists from Oregon have performed the first known instance of gene editing on human embryos in the US, according to MIT's Tech Review. Shoukhrat Mitalipov from Oregon Health and Science University and his team have reportedly corrected defective genes that cause inherited diseases in "a large number of one-cell embryos" using CRISPR. Mitalipov refused to comment on the results of the project, but some of his collaborators already confirmed them to the publication.

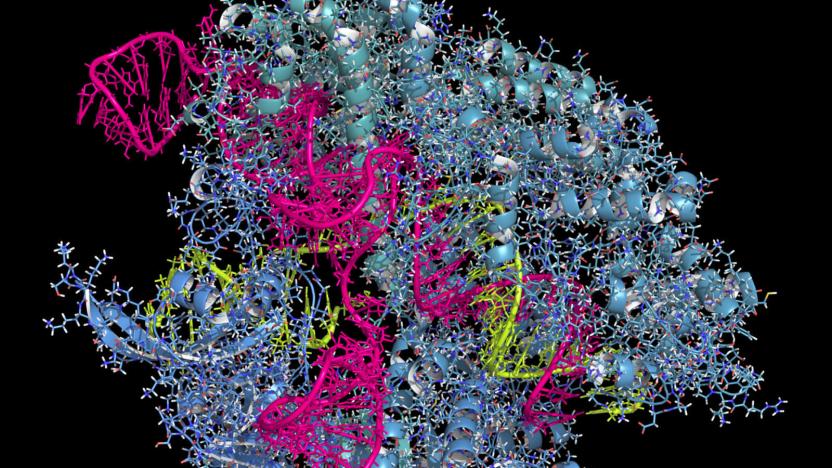

Atomic 'photos' help make gene editing safer

Believe it or not, scientists haven't had a close-up look at CRISPR gene editing. They've understood its general processes, but not the minutiae of what's going on -- and that raises the risk of unintended effects. They'll have a much better understanding going forward. Cornell and Harvard researchers have produced snapshots of the CRISPR-Cas3 gene editing subtype (not the Cas9 you normally hear about) at near atom-level resolution. They used a mix of cryo-electron microscopy and biochemistry to watch as a riboprotein complex captured DNA, priming the genes so the namesake Cas3 enzyme can start cutting. The team combined hundreds of thousands of particles into 2D averages of CRISPR's functional states (many of which haven't been seen before) and turned them into 3D projections you can see at the source link.

I bio-engineered glowing beer and it hasn’t killed me (yet)

I've been making beer for about 10 years and, in the name of fun and experimentation, I've done some weird stuff. Toss some sarsaparilla and birch bark in the pot? Why not? "Dry hop" with a box of Apple Jacks? Try and stop me. But I may have finally gone a bit too far, when I genetically engineered a beer to glow green. All right, so how did I do it? With a technology called CRISPR, which is pretty much the belle of the science ball right now. CRISPR stands for "clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats" and it essentially lets you snip out bits of DNA and replace them with whatever you want. It actually relies on a basic feature of bacterial immune systems.

Scientists use gene editing to eliminate HIV DNA in live mice

A team of scientists have snipped away HIV DNA from the genome of live mice using a CRISPR system, and the rodents lived to (kinda) tell the tale. It's still much too early to call the method a possible cure, but the fact that it worked on a living animal opens up a lot of possibilities. Will it work on other diseases, like cancer? Maybe, but that's something scientists have to look into. These researchers headed by neurovirologist Kamel Khalili have been focusing on the use of the gene-editing technique to eliminate HIV for years. They successfully excised HIV DNA in live mice last year, but this round is a lot more thorough.