CRISPR

Latest

Scientists use CRISPR to make stem cells invisible to immune system

Scientists at the University of California San Francisco have developed a new method to minimize the likelihood that a person's body will reject stem cells during a transplant. Using the CRISPR gene editing tools, the scientists managed to create stem cells that are effectively invisible to the body's immune system.

Scientists clone gene-edited monkey for circadian disorder research

Scientists in China announced this week that they've successfully made five clones of a gene-edited monkey to aid in researching a number of conditions relating to circadian rhythms. The idea is that having a group of five genetically identical monkeys will help remove variables in research, but the whole experiment raises some rather murky ethical issues as well. Researchers at the Institute of Neuroscience (ION) of Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in Shanghai intially gene-edited a group of monkeys to make it more prone to disorders that stem from circadian rhythms. Because of this gene editing, the monkeys "exhibited a wide-range of circadian disorder phenotypes, including reduced sleep time, elevated night-time locomotive activities, dampened circadian cycling of blood hormones, increased anxiety and depression, as well as schizophrenia-like behaviors." The researchers then used fibroblasts (connective tissue cells) from one monkey in that groupto produce the five clones using the same technique that successfully produced the first primate clones in early 2018.

China detains scientist who claims to have made gene-edited babies

China was quick to halt the work of scientist He Jiankui after he claimed to have created the first genetically edited babies, but that apparently wasn't enough. After weeks of uncertainty surrounding He's whereabouts, the New York Times has learned that the government has placed the researcher under house arrest at a housing facility in the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen. He can make calls and send emails, but he can't leave. Guards prevent people from getting close to either He's de facto residence or the offices involved in his research.

China halts scientist's gene-edited baby research

The scientific community and the world at large were rocked this week when researcher He Jiankui claimed he had created the world's first genetically edited babies. Using CRISPR/Cas9, He says he edited the genes of twin girls, Lulu and Nana, in order to make them more resistant to HIV. But He's work has been met with severe backlash as scientists around the world have called it irresponsible and unethical while emphasizing that CRISPR technology is not yet ready for human embryos since associated risks are not fully understood. Now, the Associated Press reports that China's government has put a hold on He's work.

Chinese scientist claims he edited babies' genes with CRISPR

A Chinese scientist claims to have created the world's first genetically-edited babies using the CRISPR/Cas9 tool. He Jiankui (pictured) told the Associated Press that twin girls, Lulu and Nana, were born earlier this month following embryo-editing using CRISPR to disable the CCR5 gene, which allows the HIV virus to infect cells. An American scientist, Michael Deem, also reportedly assisted He on the project at the Southern University of Science and Technology of China.

Lab-grown eyes explain how a baby's vision develops in the womb

Researchers at John Hopkins have grown artificial eye parts to better understand how we develop color vision. Though they don't look like eyeballs, the "organoid" retinas built from stem cells grow in much the same way as our own orbs. By using CRISPR to manipulate thyroid hormone levels, they shut off growth of green- and red-detecting cells. The results could provide new insight into how we develop color vision and help doctors treat blindness in the future.

CRISPR editing may help turn a wild berry into a farmable crop

It can take many years to make a wild plant easy to farm, but gene editing could make that happen for one fruit in record time. Scientists have used genomics and CRISPR gene editing to develop a technique that could domesticate the groundcherry, a wild fruit that's tasty and drought-resistant but difficult to grow in significant volumes. After sequencing the groundcherry's genome, the team both tweaked CRISPR to work with the plant and pinpointed the genes that led to its less-than-pleasant traits, such as its small size and not-so-plentiful flowering. From there, they just had to 'fix' the fruit with gene edits that promoted the qualities they wanted.

Researchers can track cell development through 'genetic barcodes'

A newborn is composed of roughly 26 billion cells when he or she enters the world naked, screaming and rather gooey. Figuring out how those multitudes of cells came to be from a single zygote remains among the greatest challenges in developmental biology. But researchers from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University may have finally cracked the code -- through the novel use of CRISPR technology to generate a genetic barcode.

CRISPR might cause more unintended DNA damage than we thought

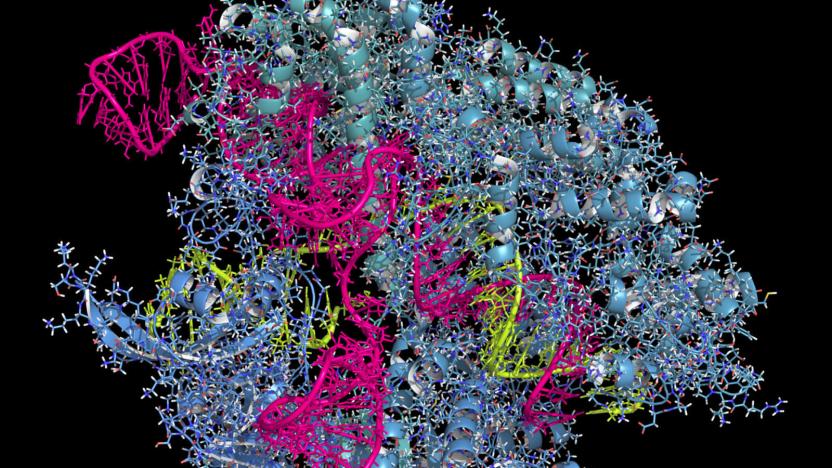

A new study published today in Nature Biotechnology warns that CRISPR may not be the ultra-specific gene editor we've believed it to be. With CRISPR-Cas9, researchers can find particular sequences in a cell's DNA and cut them at a specified spot. The cell can then repair the DNA where it was cut and scientists have been attempting to use this technique to treat all sorts of diseases and disorders including ALS, Huntington's disease, HIV and sickle cell disease. The method has been thought to be rather specific, allowing scientists to target and remove only certain sequences while leaving surrounding DNA intact. But this new study says that CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing might be causing more damage than previously reported.

Scientists reprogram T Cells to target autoimmune diseases

Researchers from the University of California, San Francisco have uncovered a gene-editing technique which could provide safer treatments for patients with cancer and autoimmune diseases. The breakthrough -- which involves the CRISPR/Cas9 system -- will allow T cells (the cells which fire up our immune response) to recognize infections with greater specificity, and eliminate the need to use viruses for transferring DNA to target cells.

Gene-edited rice plants could boost the world's food supply

Rice may be one of the most plentiful crops on Earth, but there are only so many grains you can naturally obtain from a given plant. Scientists may have a straightforward answer to that problem: edit the plants to make them produce more. They've used CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to create a rice plant variety that produces 25 to 31 percent more grain per plant in real world tests, or far more than you'd get through natural breeding. The technique "silenced" genes that improve tolerances for threats like drought and salt, but stifle growth. That sounds bad on the surface, but plants frequently have genetic redundancies -- this approach exploited this duplication just enough to provide all of the benefits and none of the drawbacks.

CRISPR pioneer wants to make an at-home test that detects disease

Biotech company Mammoth Biosciences is working on a simple, portable test that would give everyone, from healthcare professionals to just people at home, the ability to detect various diseases, infections and cancers quickly and easily. The test would use CRISPR to determine which bacteria, viruses or genetic mutations were present in a person's blood, saliva or urine and a companion app would inform users about what was detected. "Imagine a world where you could test for the flu right from your living room and determine the exact strain you've been infected with, or rapidly screen for the early warning signs of cancer," Mammoth CEO Trevor Martin said in a statement. "That's what we're aiming to do at Mammoth -- bring affordable testing to everyone."

The USDA won't regulate genetically edited plants

The US Department of Agriculture has zero plans to regulate plants altered with gene-editing technologies, according to the agency's Secretary Sonny Perdue. It won't prevent the release of crops created using CRISPR, for instance, so long as the final product is something that could've been developed through traditional breeding techniques and it's not a plant pest or achieved with the help of plant pests. That means giving plants traits like resistance to disease, chemicals or flooding and bigger seeds is A-OK, since those could be achieved at a much slower rate with traditional breeding. However, entirely new plants that aren't possible in nature created using, say, genes from several distant species, aren't acceptable.

Researchers use CRISPR to detect HPV and Zika

Science published three studies today that all demonstrate new uses for CRISPR. The gene editing technology is typically thought of for its potential use in treating diseases like HIV, ALS and Huntington's disease, but researchers are showing that applications of CRISPR don't stop there.

After Math: First!

It was a week of firsts for the tech industry. Facebook finally got around to adding its first African American board member (because it's not like it's already 2018 or anything), a lifeguard drone made its first Hasselhoffian beach rescue, Ferrari announced that it is indeed working on its first electric supercar, and Kodak took a break from slapping its brand on cryptocurrency mining rigs to release the first footage from its upcoming hybrid Super 8 camera. Numbers, because how else will you put entrants in order?

First human CRISPR study in the US could begin soon

In mid-2016, A federal panel had greenlit the University of Pennsylvania to pursue the first trials using CRISPR gene-editing in the US. It seems the institution has quietly gotten the ball rolling and could theoretically start the study at any time: A posting was found on a directory of trials describing a yet-to-be-scheduled UPenn survey using CRISPR techniques to treat cancer patients.

Key CRISPR gene editing methods might not work for most humans

At first glance, CRISPR gene editing looks like the solution to all the world's ills: it could treat or even cure diseases, improve birth rates and otherwise fix genetic conditions that previously seemed permanent. You might want to keep your expectations low, though. Scientists have published preliminary findings indicating that two variants of CRISPR Cas9 (the most common gene editing technique) might not work for most humans. In a study, between 65 percent and 79 percent of subjects had antibodies that would fight Cas9 proteins.

New CRISPR tool alters RNA for wider gene editing applications

The CRISPR gene editing technique can be used for all sorts of amazing things by targeting your DNA. Scientists are using it in experimental therapies for ALS and Huntington's disease, ways to let those with celiac disease process gluten proteins and possibly assist in more successful birth rates. Now, according to a paper published in Science, researchers have found a way to target and edit RNA, a different genetic molecule that has implications in many degenerative disorders like ALS.

Gene editing could make wheat safe for celiac sufferers

Celiac disease is thought to affect 1 in 100 people worldwide. Although doctors are still grappling with the causes of the autoimmune disorder, one thing is for sure: If you're diagnosed it with it, you should avoid gluten. But maintaining long-lasting dietary changes isn't easy -- especially when you have to discard some of the most common food items, like bread. Fortunately, hope may be at hand, thanks to good old science. Using gene-editing, researchers from Spain's Institute for Sustainable Agriculture are creating new types of wheat that reduce immune reactions in celiac disease sufferers.

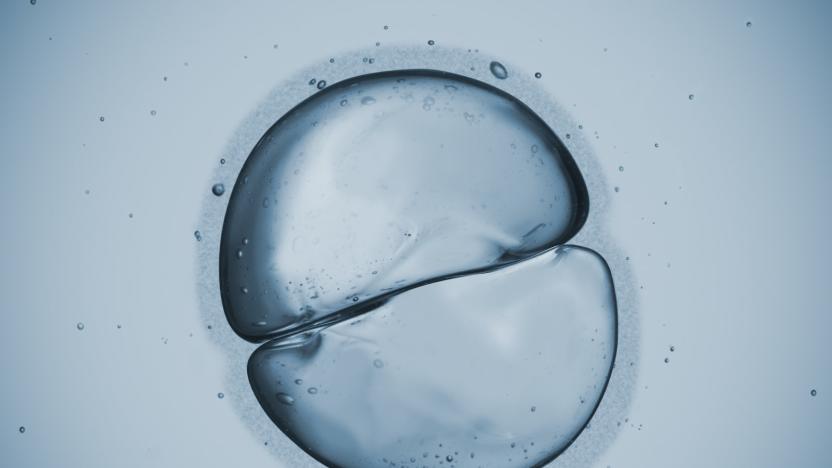

CRISPR gene-editing could result in more successful birth rates

Gene-edited human embryos are offering new insights into the earliest stages of development, and could reduce the risk of miscarriage at the outset of pregnancy. In a new study, researchers from the UK's Francis Crick Institute used CRISPR Cas9 to block a gene (known as OCT4) in human embryos. By stopping it from functioning, the researchers saw that it no longer produced its resulting protein (also called OCT4). As a result, the human embryos ceased to attach or grow sufficiently. Their findings, published in the journal Nature, illustrate the importance of the gene in human development.